that “[t]he gun lobby’s interpretation of the Second Amendment is one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word fraud, on the American People by special interest groups that I have seen in my lifetime.” Many have never stopped repeating this sentiment, such as a

by Michael Waldman in Politico Magazine which began with that quote from Burger, then went on to claim that:

From 1888, when law review articles first were indexed, through 1959, every single one on the Second Amendment concluded it did not guarantee an individual right to a gun….Then, starting in the late 1970s, a squad of attorneys and professors began to churn out law review submissions, dozens of them, at a prodigious rate. Funds—much of them from the NRA—flowed freely….This fusillade of scholarship and pseudo-scholarship insisted that the traditional view—shared by courts and historians—was wrong. There had been a colossal constitutional mistake. Two centuries of legal consensus, they argued, must be overturned.

submitted by Global Action Against Gun Violence and several professors to the Supreme Court. They urged the Court to reverse Heller and with it, recognition of the individual right to keep and bear arms.

-

This article is an adaptation of my pinned historical sources

, as well as some sources from

done by

, who continued to find more and more sources long after I had mostly moved on and stopped updating my thread as frequently. The thread became quite unwieldy and hard to read, prompting me to put it in this article form. I’ve done my best to give this some semblance of organization by the type of person being cited (political figure, scholar/judge, etc.)

-

I have not included every source, because some are just too obscure and repetitive. But I have included many, and certainly all of the high profile examples. If you want total comprehensiveness, the threads are still your best option. For this article, I focused mostly on commentary from prominent people of the era.

-

The original plan was to have images for every source, like the thread does. Unfortunately, I learned that there is a limit on how many images a Twitter article can have, so now only some of the entries have images. Almost every entry has a clickable link to the full text, plus also a link to the author’s biographic information on their bolded name (save for a few obscure writers for whom a biography could not be found online).

-

This article will not be much fun to read, frankly. It is much too long to be all that readable. Treat it more like a reference, or a tool to win arguments with the latest person who cites Justice Burger’s famous quote or makes similar arguments. I have made every effort to make it as readable as possible, and include links to the sources.

-

Founding-era commentary and court rulings are not the focus here. That has been written about extensively elsewhere, and covered in Heller and McDonald. Much less attention has been paid to 19th century Americans and what they thought. That said, many of the earliest commentators were contemporaries of the founders, and sometimes were appointed to positions of power by them.

-

This is not an original idea. As I would find out after I spent hours on Google Books digging up sources,

did similar work decades ago, and wrote a masterful scholarly article on the topic which can be read

.

-

I had worked with

to coauthor

on this topic in 2022 on his excellent website, the Reload. If you don’t have time to go through this behemoth of an article, just go read that one and you’ll get a decent understanding in a much easier to read form. But this article will include more sources than that one did.

-

Finally, if you appreciate this work, I hope you’ll

. They are why I am privileged enough to be able to do what I do.

actually was a founding father (albeit a lesser-known one), serving as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention from Pennsylvania. He would also serve in the Washington administration as an Assistant Secretary of the Treasury from 1789-1792.

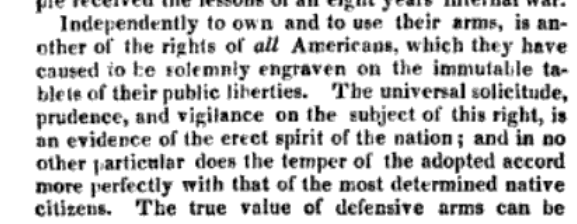

that the “militia” referenced in the Second Amendment “embraces all the free white males of the proper ages.” Calling this “the army of the constitution”, Coxe explained that “[t]hey have all the right, even in profound peace, to purchase, keep and use arms of every description.” But Coxe also made clear this was not a right only for white males of the proper age. He referred to the “right to own and bear arms” as one of the constitutional liberties “extended to all the people of the United States.” He said as much repeatedly:

of letters and other writings from the aging founders in this time period, in which they debated ideas and discussed their reflections on the system of government they had created. This provides strong evidence that the Second Amendment recognized an individual right, and this was so uncontroversial a view that it was barely discussed.

is another early example. In 1791, President Washington appointed Rawle United States district attorney for Pennsylvania, a position he served in from 1791 to 1800. After that, he would serve as the first chancellor of the Pennsylvania bar association, and in 1805, he argued before the United States Supreme Court that slavery was unconstitutional.

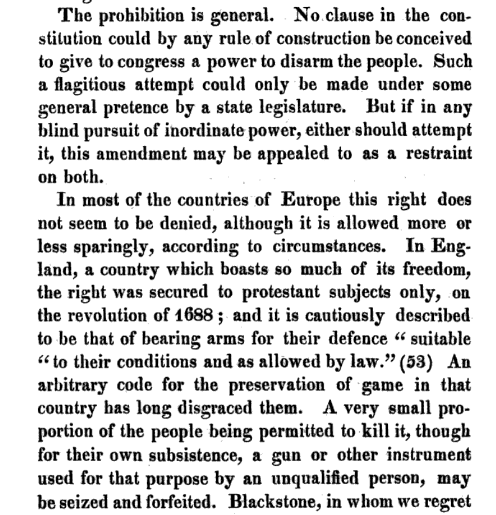

, Rawle explained that the Second Amendment prohibited congress from disarming the people. He contrasted the right from its much more limited English version, complaining that the latter had effectively disarmed most of its subjects.

of Pennsylvania, a member of Congress from 1809-1815 and 1817-1819, wrote in his 1818

that the constitution “guarantees to every citizen” the right to keep and bear arms, which other countries do not do.

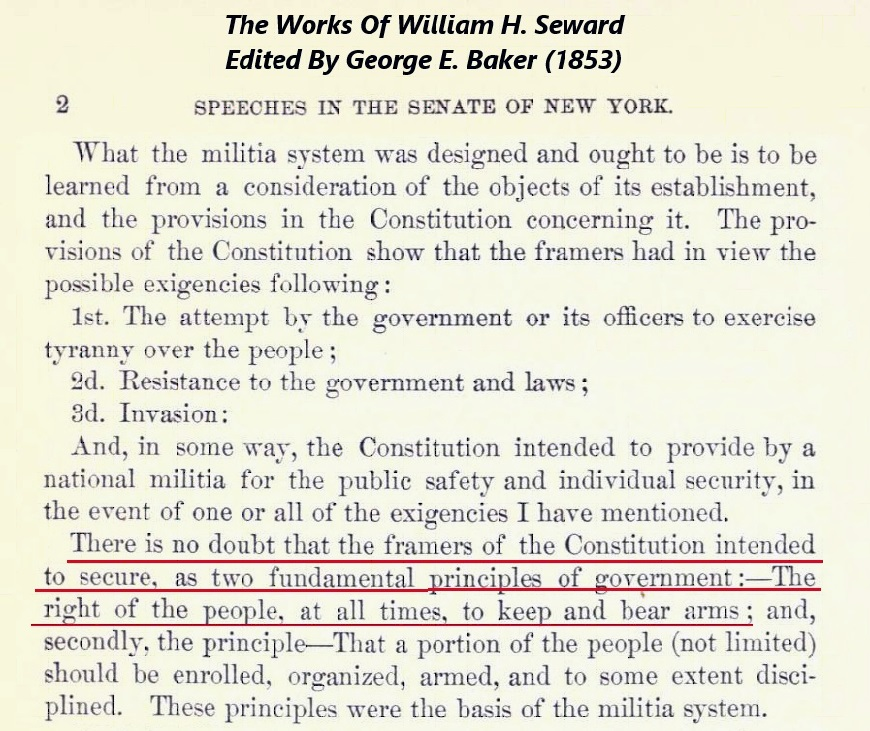

was our 24th Secretary of State, serving under Presidents Lincoln and Johnson. He was also a Senator and Governor of New York. He considered the right of the people “at all times, to keep and bear arms” to be one of the two fundamental principles of government the framers meant to secure.

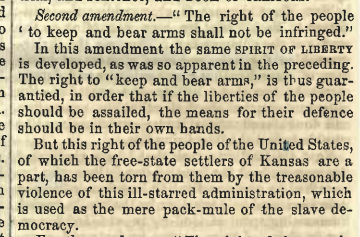

of Ohio, an abolitionist, gave a

in the House of Representatives in 1856 during the events now known as “Bleeding Kansas”. In that speech, he complained that Kansas settlers who opposed slavery were having their right to keep and bear arms violated by the current administration. As we’ll see later in the thread, abolitionists spoke often about the individual right to keep and bear arms.

’s 1856 speech “

” bristled at the mere suggestion that citizens in Kansas who opposed slavery should be disarmed of their Sharps rifles by the proslavery government: “Never was this efficient weapon more needed in just self defence, than now in Kansas, and at least one article in our National Constitution must be blotted out, before the complete right to it can in any way be impeached.”

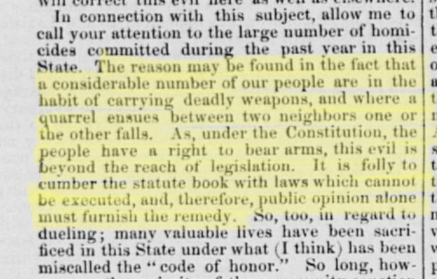

of California (also previously a Senator from 1852-1857) wrote in an 1860

to the legislature that homicides were too high, casting blame on people in the habit of carrying deadly weapons. But he acknowledged that there was not much that could be done, because the Constitution secured the right to keep and bear arms.

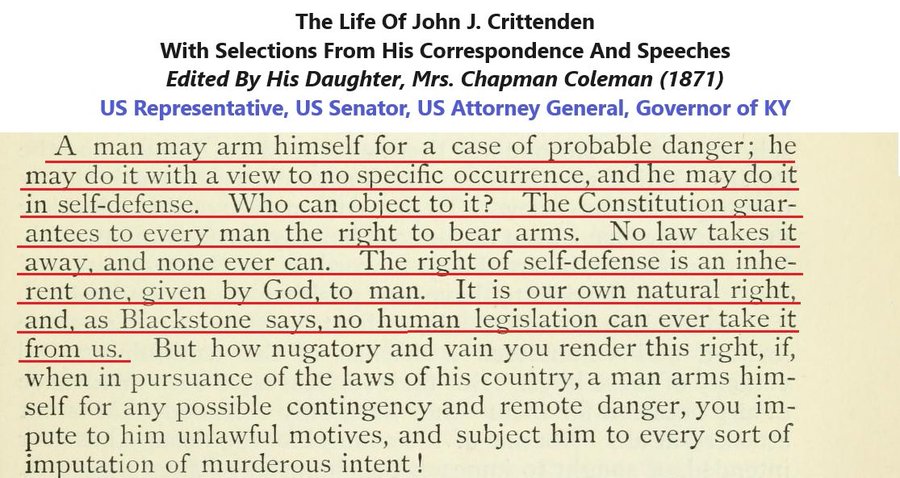

has perhaps the most extensive resume of any source presented here. In reverse chronological order, he served as a Representative from Kentucky (1861-1863), Senator (1855-1861), Attorney General for President Fillmore (1850-1853), Governor of Kentucky (1848-1850), and Secretary of State of Kentucky (1834-1835).

of Ohio, who served in Congress from 1858-1863, gave a

opposing civil war-era restrictions on the sales of arms, powder, lead, and percussion caps, citing the Second Amendment for why the restrictions were unacceptable.

, who after the civil war served with the Freedmen’s Bureau until late in 1866,

that all men, regardless of race, have the right to keep and bear arms to defend their homes, families, and themselves.

, a Medal of Honor recipient and Assistant Commissioner for the Freedmen’s Bureau after the Civil War, wrote that the seizure of arms from freedmen violated their Second Amendment rights. This was printed in the

.

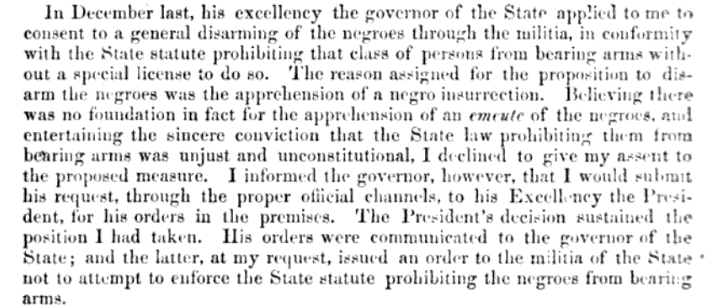

, in charge of overseeing Tennessee,

in 1866 that the governor of the state asked him for permission to disarm black people based on dubious speculation that they would revolt if they continued to be armed. The General said no because that would be “unjust and unconstitutional”, and President Johnson agreed.

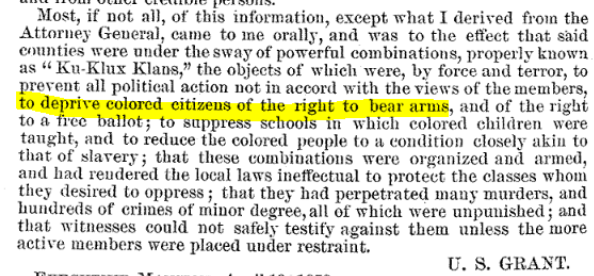

complained in a letter to Congress in 1872 that the Ku Klux Klan’s objectives were “by force and terror, to prevent all political action not in accord with the views of the members, to deprive colored citizens of the right to bear arms…and to reduce the colored people to a condition closely akin to that of slavery.” See H. Journal, 42nd Cong., 2d Sess. 716 (1872).

was a lawyer, military officer, and law professor at the College of William and Mary. He wrote an

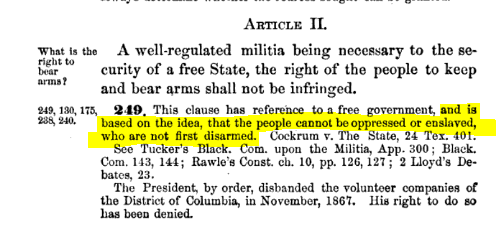

of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, the first of its kind in the United States and a valuable reference work for many American lawyers and law students of the time. In 1813, President James Madison appointed Tucker to the federal bench, making him a judge of the United States District Court for the District of Virginia, where he served until he resigned in 1825.

, who would later serve as a New York state court judge, wrote

(1840). There, he described the Second Amendment as arming “the citizen” to protect against foreign aggression and be the “sentinel of his liberties.”

wrote several books on law between 1852 and 1871. As to the Second Amendment, his view expressed in his 1860 book

was that the very fact the people were armed served as a check on an invasion of their rights.

was an interesting character for his era. After law school, in 1832 he served as an aide to General John E. Wool, who was removing Cherokee Indians to Indian territories. While on that expedition, he married a Cherokee woman. In 1837 Paschal moved to Arkansas and, before he was thirty, was appointed by the Arkansas legislature as associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court. But he resigned a year later to represent the Cherokee in various claims against the US government. He also had an unsuccessful run for Attorney General of Texas, and edited an Austin newspaper, frequently commenting against secession.

(1868). It is the latter we are interested in, as it includes his brief commentary on the Second Amendment, in which Paschal explains that the Second Amendment exists so the people can resist a tyrannical government.

was an esteemed lawyer, abolitionist, and legal treatise writer.

on the Second Amendment, written in 1868, was more limited than many of his contemporaries. He read the provision as applying only to weapons useful for warfare, not those used in “brawls”. But he still clearly saw it as protecting an individual right. Interestingly, like his fellow abolitionist Horace Greeley, he was also ahead of his time in arguing the Second Amendment also was binding on state governments, a minority view at the time.

was a judge of the New Hampshire Court of Common Pleas from 1824 to 1832, and also briefly served in the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1854. His

listed the Second Amendment (described simply as “a right to keep and bear arms”) as one of the “many natural and civil common-law rights” that are “expressly reserved” by the people.

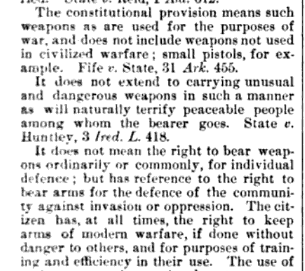

, a lawyer who served as the secretary of the New York Code Commission (which drew up the state’s penal code in 1864),

that the Second Amendment “does not extend to carrying bowie knives, fire-arms . . . concealed upon the person; or prohibit legislative regulations of the manner in which arms may be carried. . . . The constitutional provision means such weapons as are used for the purposes of war.”

was elected to the California State Senate in 1879, but was denied his seat because he was born in Canada. Like most writers of his time, his

viewed the Second Amendment as protecting a preexisting natural right, but only from federal infringement. Also like most of his contemporaries, he cited the anti-tyranny purpose of the Second Amendment.

was a German-American historian and author. He emigrated to the United States and wrote extensively on the Constitution of the United States, largely from an anti-slavery perspective.

explained that while some argue the arms the Second Amendment protects are only those used by the militia, “it must not be inferred from this that the right is restricted to those citizens who belong to the militia.”

was a law professor, and

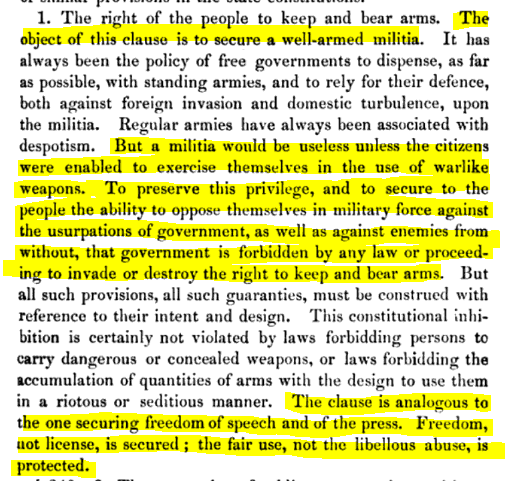

text book writers of the last third of the nineteenth century. His work

(1888) shows how the objective of securing a well-armed militia is hardly mutually exclusive with an individual right. Instead, it is wholly dependent on it.

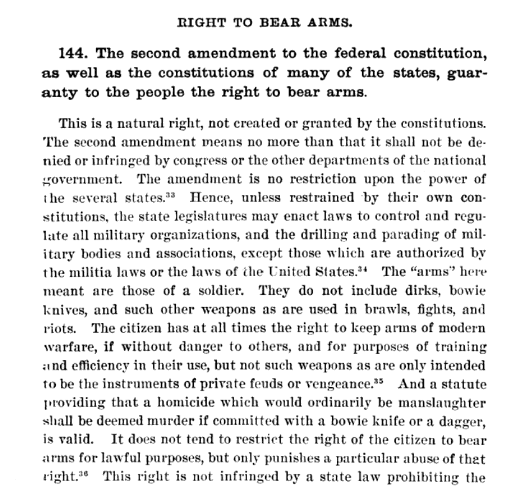

is most famous for being the original author of Black’s Law Dictionary, which is still updated to this day. His

considered the Second Amendment an individual right, albeit one that only applied to the arms of “modern warfare”. “It does not tend to restrict the right of the citizen to bear arms for lawful purposes, but only punishes a particular abuse of that right.”

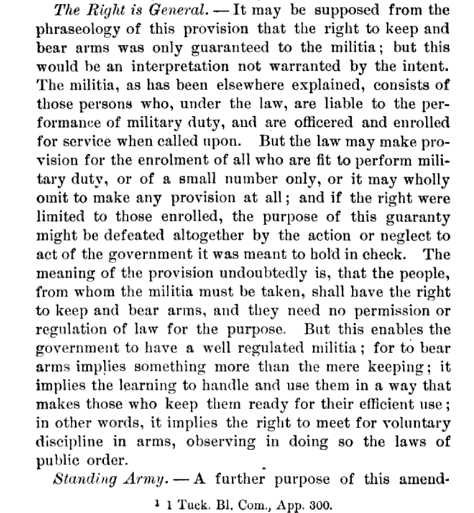

was one of the most influential legal minds of his time, and served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of Michigan from 1864 to 1885. A modern law school is named after him (

in Lansing, Michigan).

(first published in 1880) says of the Second Amendment that its meaning “undoubtedly is” that the people have the right to keep and bear arms, and they need no permission to do so. This also enables the government to have a militia.

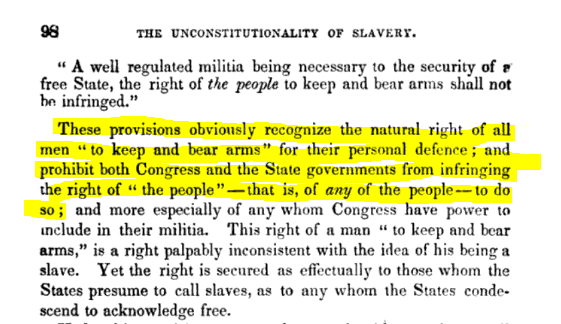

, a prolific writer of the 19th century, wrote in his work

that the Second Amendment protects the right of individual to defend themselves. And this right belongs to everyone, because no limit on it is included.

, now considered an early libertarian writer, was an abolitionist, entrepreneur, lawyer, essayist, natural rights legal theorist, and political philosopher.

the individual right interpretation the “obvious” one.

, the famous American newspaper editor, abolitionist, and briefly a member of Congress,

that not only did the Second Amendment protect an individual right, but it also could not be infringed by any state.

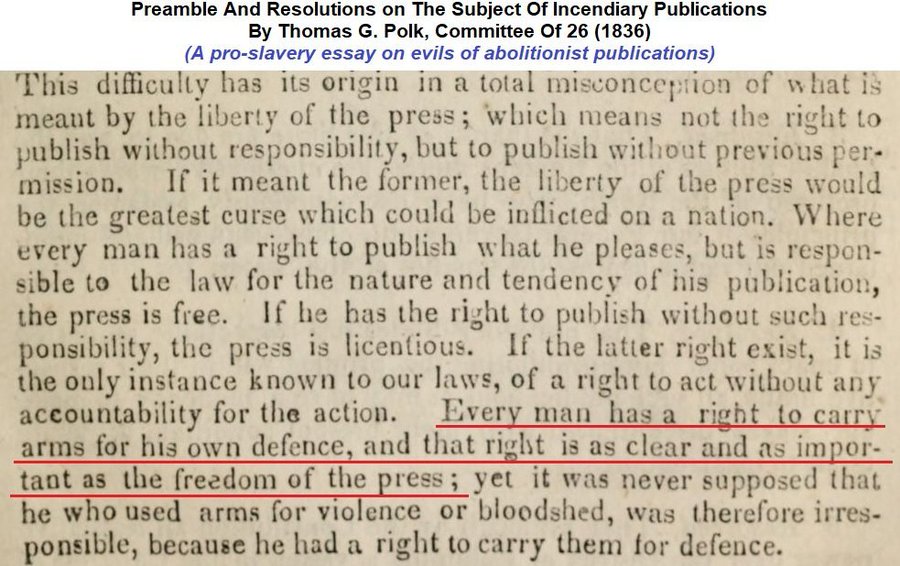

.

would find little in common with abolitionists, he did

on the individual right view of the Second Amendment:

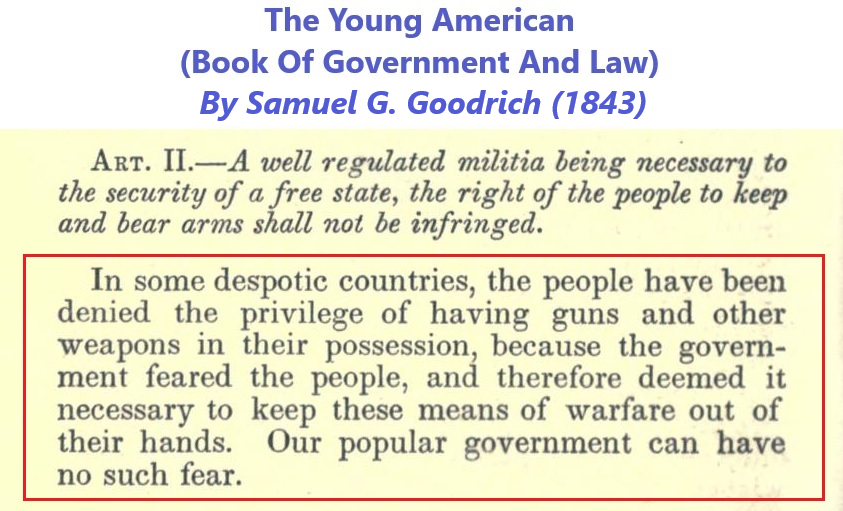

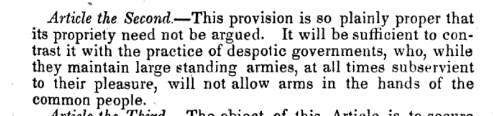

had a brief political career, serving in both the Massachusetts State Senate and House of Representative for a short time in each. In terms of the Second Amendment,

in his book for young people that it contrasted from the practices of despotic governments.

(1848). He viewed the Second Amendment as abundantly clear:

wrote in

that it is “scarcely necessary to say” that the right to bear arms is the foundation of the people’s liberties.

(1880) The book said the Second Amendment allowed citizens to own and use “warlike weapons” in order to prevent tyranny.

was the daughter of a United States Senator. She was a pretty prolific writer and accomplished in her own right, serving as a correspondent for various newspapers. Her opposition to women’s suffrage may be part of the reason why she has fallen into obscurity today.

in her 1885 textbook for young people that prohibiting people from bearing arms entirely would go too far because it would take away all possibility of resisting injustices. That said, she said the right did not cover concealed carry.

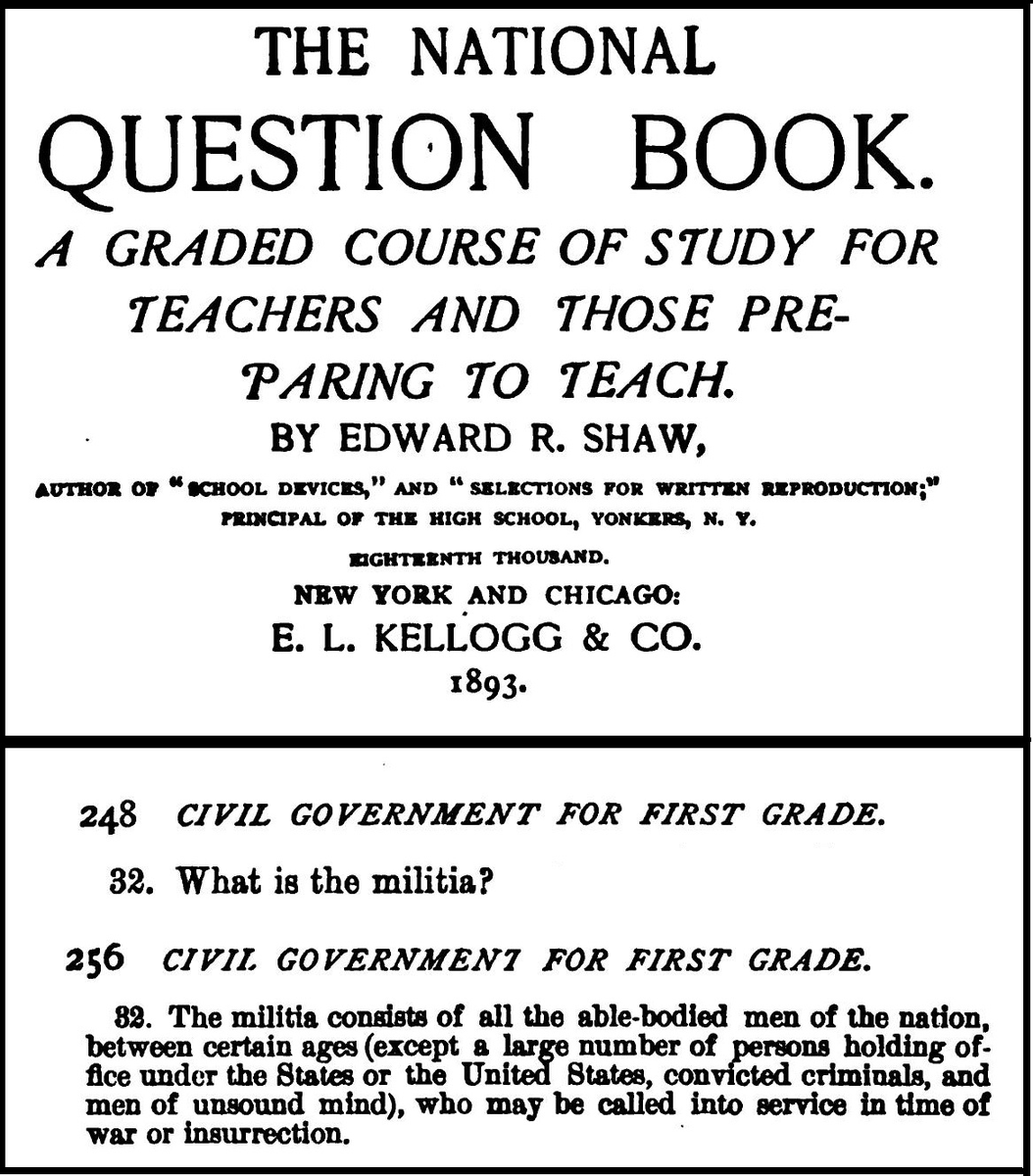

‘s 1893

for teachers says that even first graders should know that the militia consists of all able-bodied men in the nation.

was a teacher and civic activist. In 1900, her book

said of the Second Amendment that it does not mean that only the militia may bear arms, but that every citizen may do so.

. Or

.