How Many Historical Gun Laws Constitute a ‘National Tradition’?

The Supreme Court has explicitly stated that, in order for a modern gun law to be constitutionally sound, it must comply with the text of the Second Amendment as well as the history and tradition of gun ownership (and gun regulation). So far, though, the Court hasn’t given a whole lot of advice as to what constitutes a national tradition.

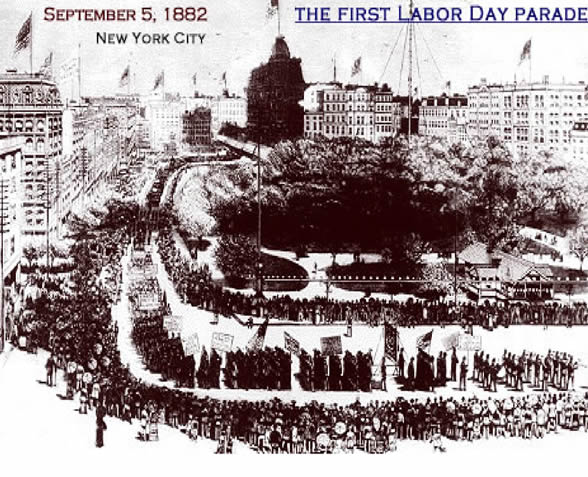

In Bruen, SCOTUS doubted that “just three colonial regulations could suffice to show a tradition of public-carry regulation,” but declined to state definitely what would suffice; both in terms of the number of laws as well as when those laws were put into effect. Is 1791 the most important date, since that’s when the Second Amendment was ratified; is it 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified; or are both equally important?

Pete Patterson, an attorney at Cooper & Kirk with an extensive background as a Second Amendment litigator, was asked about this by SCOTUSblog’s Haley Proctor for her 2A-focused series “A Second Opinion,” and his answer worth discussing.

What does it take to make a sufficient showing of a history of firearms regulation? How many laws or practices do you need, from what historical period, and how do we describe the tradition those laws represent?

These are all issues that are hotly contested, but I will give you what I think is the view most consistent with Bruen and Supreme Court precedent generally.

First, the relevant historical period should be centered on 1791, when the Second Amendment was ratified. The court has held in many cases that when provisions of the Bill of Rights apply to the states, they have the same meaning as they have against the federal government.

It should follow that the meaning was set in 1791, when those provisions were first ratified and applied to the federal government. To be sure, those rights were not incorporated against [applied to] the states until the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, but that amendment did not purport to change the substantive meaning of the Bill of Rights.

This conclusion is consistent with the court’s practices, including its holding in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue that the laws of over 30 states from the second half of the 19th Century could not alone “establish an early American tradition” that would inform the meaning of the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

That makes sense, both from a legal and practical standpoint. As Patterson points out, there’s nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment that suggests any type of revision to the Bill of Rights. It’s purpose wasn’t to update the Bill of Rights, but to ensure that those rights were safeguarded against intrusion by state and local governments as well. And during the congressional debate over the Fourteenth Amendment, the right to keep and bear arms was front and center.

Second, what the government should have to establish is a limitation that was widely understood by Americans at ratification to qualify the scope of the right to keep and bear arms.

The common law frequently will be a primary resource in this inquiry, as that was law that was understood to be generally applicable. The common law is reflected in sources like case law and prominent secondary sources such as Blackstone’s Commentaries.

Of course, the focus should be on the prevailing American understanding rather than British understandings that Americans may have repudiated, so consulting American sources like Tucker’s Blackstone is an important part of the inquiry.

Statutes also play a role, of course, but the government should have to show that any statutes it relies on are consistent with the prevailing, general understanding and not a departure from it. That presumably is why Bruen repeatedly emphasizes that a handful of outlier statutes cannot establish a tradition of regulation.

I think its also important to note that the Supreme Court talked about a “national” tradition, not a state-specific or regional tradition. If three colonial-era statutes aren’t enough to suffice, then three statutes from one part of the country shouldn’t be enough either. This is particularly important when courts are considering laws adopted around the time the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, given that many southern states instituted laws restricting the right to keep and bear arms that might have been racially neutral on their face, but were hardly enforced in a colorblind fashion.

Patterson adds one more metric in determining a “national tradition.”

Third, the tradition should be described at a level of generality that is general enough not to make arbitrary distinctions, but specific enough not to risk eviscerating the right.

If readers are interested in the level-of-generality question, I recommend the brief my colleague John Ohlendorf filed in Wolford on behalf of professor [Joel] Alicea, which address that question at some length.

As an example of the need for the Court to address the level of generality that’s most appropriate, Ohlendorf cites the historical tradition recognized in Bruen of states prohibiting arms “in legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses.”