The triumph of persuasion over force is the sign of a civilized society.

— Mark Skousen

January 12, 2026

You are only an Apex Predator when armed – Zendo Deb

January 11, 2026

How Many Historical Gun Laws Constitute a ‘National Tradition’?

The Supreme Court has explicitly stated that, in order for a modern gun law to be constitutionally sound, it must comply with the text of the Second Amendment as well as the history and tradition of gun ownership (and gun regulation). So far, though, the Court hasn’t given a whole lot of advice as to what constitutes a national tradition.

In Bruen, SCOTUS doubted that “just three colonial regulations could suffice to show a tradition of public-carry regulation,” but declined to state definitely what would suffice; both in terms of the number of laws as well as when those laws were put into effect. Is 1791 the most important date, since that’s when the Second Amendment was ratified; is it 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified; or are both equally important?

Pete Patterson, an attorney at Cooper & Kirk with an extensive background as a Second Amendment litigator, was asked about this by SCOTUSblog’s Haley Proctor for her 2A-focused series “A Second Opinion,” and his answer worth discussing.

What does it take to make a sufficient showing of a history of firearms regulation? How many laws or practices do you need, from what historical period, and how do we describe the tradition those laws represent?

These are all issues that are hotly contested, but I will give you what I think is the view most consistent with Bruen and Supreme Court precedent generally.

First, the relevant historical period should be centered on 1791, when the Second Amendment was ratified. The court has held in many cases that when provisions of the Bill of Rights apply to the states, they have the same meaning as they have against the federal government.

It should follow that the meaning was set in 1791, when those provisions were first ratified and applied to the federal government. To be sure, those rights were not incorporated against [applied to] the states until the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, but that amendment did not purport to change the substantive meaning of the Bill of Rights.

This conclusion is consistent with the court’s practices, including its holding in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue that the laws of over 30 states from the second half of the 19th Century could not alone “establish an early American tradition” that would inform the meaning of the First Amendment’s establishment clause.

That makes sense, both from a legal and practical standpoint. As Patterson points out, there’s nothing in the Fourteenth Amendment that suggests any type of revision to the Bill of Rights. It’s purpose wasn’t to update the Bill of Rights, but to ensure that those rights were safeguarded against intrusion by state and local governments as well. And during the congressional debate over the Fourteenth Amendment, the right to keep and bear arms was front and center.

Second, what the government should have to establish is a limitation that was widely understood by Americans at ratification to qualify the scope of the right to keep and bear arms.

The common law frequently will be a primary resource in this inquiry, as that was law that was understood to be generally applicable. The common law is reflected in sources like case law and prominent secondary sources such as Blackstone’s Commentaries.

Of course, the focus should be on the prevailing American understanding rather than British understandings that Americans may have repudiated, so consulting American sources like Tucker’s Blackstone is an important part of the inquiry.

Statutes also play a role, of course, but the government should have to show that any statutes it relies on are consistent with the prevailing, general understanding and not a departure from it. That presumably is why Bruen repeatedly emphasizes that a handful of outlier statutes cannot establish a tradition of regulation.

I think its also important to note that the Supreme Court talked about a “national” tradition, not a state-specific or regional tradition. If three colonial-era statutes aren’t enough to suffice, then three statutes from one part of the country shouldn’t be enough either. This is particularly important when courts are considering laws adopted around the time the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, given that many southern states instituted laws restricting the right to keep and bear arms that might have been racially neutral on their face, but were hardly enforced in a colorblind fashion.

Patterson adds one more metric in determining a “national tradition.”

Third, the tradition should be described at a level of generality that is general enough not to make arbitrary distinctions, but specific enough not to risk eviscerating the right.

If readers are interested in the level-of-generality question, I recommend the brief my colleague John Ohlendorf filed in Wolford on behalf of professor [Joel] Alicea, which address that question at some length.

As an example of the need for the Court to address the level of generality that’s most appropriate, Ohlendorf cites the historical tradition recognized in Bruen of states prohibiting arms “in legislative assemblies, polling places, and courthouses.”

Don’t do what Mr. Griffin did.

Criminal defense attorney explains manslaughter charges after suspected burglar killed

MEMPHIS, Tenn. (WMC) – A man has been charged with voluntary manslaughter after admitting to police that he shot a burglary suspect.

This happened on Robin Hood Lane in Memphis this Thursday. Marques Griffin, 30, told police he heard a noise in his apartment and found a man in his living room.

According to MPD, Griffin followed the intruder outside and fired three shots as the man ran away.

The suspected burglar died at the hospital.

Phil Harvey, the owner of Harvey Criminal Defense Lawyers, said that based on Griffin’s charges, MPD and the DA’s office decided he did not have a legitimate self-defense claim.

“If it’s true that Mr. Griffin shot someone outside of the home, then there’s a question of whether or not that self-defense statute applies,” said Harvey.

Harvey said Tennessee does not have a “Stand Your Ground” law.

He said the self-defense statute is written to apply when the victim is in their home and responding to a threat who is also inside or actively coming in.

“The standard ‘no duty to retreat’ part of that statute simply says you have to have a reasonable fear of what they call ‘imminent danger,’” said Harvey.

Harvey said that means that for deadly force to be considered self-defense, the victim has to be under an immediate threat of death or serious bodily injury.

Harvey said there is established case law on this type of incident.

“Tennessee v. Garner… It’s a 1985 case. A U.S. Supreme Court case that came out of Tennessee that actually dealt with whether or not police can shoot a fleeing felon. And in that case, it dealt with a burglary suspect who was running away and was shot by the police. And the federal courts decided that it is a violation of the Fourth Amendment,” said Harvey.

Griffin remains behind bars on a $50,000 bond and is slated to reappear in court on Monday.

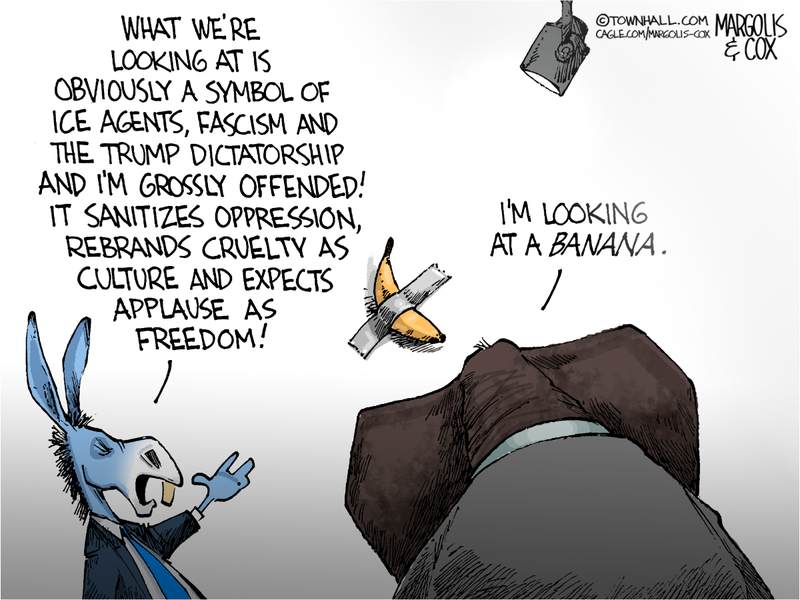

Portland Police Chief Cries After Admitting Suspects in Border Patrol Truck Attack Are Tren de Aragua Associates

Portland Police Chief Bob Day knew on the first day but withheld this information from the public as leftists urged violent revenge against federal agents

Portland Police Chief Bob Day broke down and cried at a press conference on Jan. 9 after being forced to concede that DHS was right all along: the illegal Venezuelan migrants accused of trying to run down Border Patrol agents the day before in Portland have ties to the violent Tren de Aragua gang. Day admitted he hesitated to tell the public the truth.

On Jan. 8, Border Patrol agents non-fatally shot Luis David Nico Moncada and Yorlenys Betzabeth Zambrano-Contreras in east Portland after the suspects allegedly tried to ram them down with a red pickup truck during a targeted stop. Almost immediately, internal details falsely claiming it was an ICE shooting were leaked to the extremist group PDX ICE Watch by a Multnomah County first responder.

Instead of waiting for facts, Portland and Oregon leaders — all Democrats — rushed to stage an emergency press conference condemning federal agents, rejecting DHS’ statements, and publicly siding with the violent suspects, whom they repeatedly described as “victims.” Corporate media followed suit, misleading the public and inflaming tensions. The Portland Police chief refused to share the truth about the suspects’ Tren de Aragua ties.

At night on Jan. 8, an angry far-left mob descended on the Portland ICE facility, attempting to attack it and forcing police to make six arrests — all sparked by misinformation pushed by elected officials, activists and media.

Portland Police @ChiefBobDay cries at a press conference after having to affirm that @DHSgov was correct in stating that the illegal Venezuelan migrants accused of trying to run down Border Patrol have ties to Tren de Aragua. Chief Day admitted that he hesitated to share the… pic.twitter.com/wxdT53yWsD

— Andy Ngo (@MrAndyNgo) January 10, 2026

v

“There is a true law, a right reason, conformable to nature, universal, unchangeable, eternal, whose commands urge us to duty.”

– Cicero

January 10, 2026

When you’ve lost other moslems…..

Not Satire: UAE Cuts Funding For Students In UK Because They May Encounter Radical Islam.

BREAKING:

The UAE announces it will cuts funds for citizens who want to study in the UK out of fear of Emirati students being radicalized by Muslim Brotherhood Islamists on British campuses.

An Arab state now views a European state as a dangerous Islamist radicalization hotspot pic.twitter.com/uqCxDuDwvr

— Visegrád 24 (@visegrad24) January 9, 2026

The word “debunked” gets thrown around an awful lot by the leftist media, and it’s amazing how often it really boils down to “we said it’s false and that’s all you need to know.”

Tilting At Windmills is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Now, if the media were trustworthy, that might be enough. If someone is worthy of trust, you can take their word at face value. The phrase “trust me, bro,” isn’t needed when someone is trusted.

But I came across a story earlier today that, frankly, highlights how the leftist media’s myths can, in fact, be prophecy.

In 2009, former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin created a sensation when she claimed that government-run healthcare would inevitably lead to the creation of bureaucratic boards responsible for deciding who should and shouldn’t receive treatment.

It’s from this charge that we got the term “death panel,” which became a near constant reference during the congressional debate over the passage of the Affordable Care Act.

Palin was called a loon and a crank.

Even today, a simple search on Microsoft’s Copilot for the date when the former governor coined the term “death panel” carefully notes that her accusation quickly became a viral talking point despite “being widely debunked as a myth.”

Fifteen years after Palin’s remark, disability advocate Krista Carr testified before members of the Canadian parliament that her organization receives weekly reports of medical assistance in dying (MAID) services being suggested unprompted to disabled individuals during routine, non-terminal care visits.

Who could have predicted that government-controlled healthcare, combined with legalized euthanasia, would eventually lead to the sick and uncomfortable being told to kill themselves?

Where does Palin go for her apology?

Palin was a flawed candidate, whom I mocked at the time as well, but on this, she was right. While there may not be an express panel simply deciding who lives and who dies, the fact that Canada, with its socialized healthcare system, finds it cheaper to kill patients rather than treat them, so they suggest suicide.

How is that better than simply denying treatment so people can waste away slowly? Is it a bit more humane? That depends on your perspective, but the point is that they’re still trying to use MAID to rid their system of people who require more care and, as a result, cost more money.

This was “debunked as a myth,” but that “myth” was nothing of the sort.

It’s like how the media keeps trying to claim that gun bans aren’t on the table simply because a candidate isn’t expressly talking about them at that particular moment.

When anyone on the right makes a logical inference on the result of a given policy, even if it’s not expressly spelled out as such in the proposals being discussed, the media turns to the text and calls BS, even if anyone with half a brain can see where that’s coming from.

It’s not that different than CNN calling Minnesota day cares and reporting that the one that answered the phone said it was legit, so everything Nick Shirley uncovered was debunked.

To call it asinine is too mild a term for this level of vile.

The truth is that while I’m a big fan of pointing out when the Law of Unintended Consequences rears its ugly head, there are many times we can see those consequences coming from a mile away.

Like “death panels” being the ultimate result of state-run healthcare. Like gun control’s failures eventually leading to a proposal for banning firearms almost entirely. Like making fraud easy results in fraud.

The difference between the mythology of Palin’s warning and what we can now see was clearly prophecy is a matter of time.

Meanwhile, there’s absolutely no mainstream coverage of the supposed prophecies of how the Bruen decision was going to lead to more homicides on our streets, which has now been debunked not by the media but by history.

Violent crime is down. Homicides are down. “Mass shootings” are down. Everything is down compared to where it was when Bruen was decided.

Nothing they said would happen actually happened, but they don’t talk about that being “debunked.” That would mean acknowledging that their buddies were wrong, that they didn’t know what they were talking about.

It’s like the prophecies of climate change. Every model is, in essence, an attempt at prophecy, though one based on supposed science rather than mysticism. Yet those models have a track record that would only be improved if they relied on pig entrails or tarot cards.

Those are never framed as “debunked,” either.

Weird, isn’t it?

The difference between mythology and prophecy, at least in this context, is nothing more than the media’s continued fixation on advancing leftist policies, downplaying anyone on the right, and otherwise being anything but the journalists they want us to believe they are.

Those, who have the command of the arms in a country are masters of the state, and have it in their power to make what revolutions they please.

Thus, there is no end to observations on the difference between the measures likely to be pursued by a minister backed by a standing army, and those of a court awed by the fear of an armed people. — Aristotle