We Need to Rethink Our Assumptions About Nuclear Weapons Use

One of the Strategic Purposes of the Kursk Offensive

I was struck by the messaging of the Ukrainian government over the last 24 hours—and just how it has tied the need for long-range strike into the strategic purpose of the Kursk Offensive. Its both an immediate question, and at the same time a broad one about how and when nuclear weapons might be used. What Ukraine is doing, is driving an invasion force directly through an existing consensus—basically saying the emperor has no clothes when it comes to nuclear weapons usage. The Ukrainians are saying all your assumptions and strategic plans on nuclear weapons are wrong—and they seem to be right. The implications of this are profound.

The Kursk Offensive and Nuclear Red-Lines

The Kursk Offensive by Ukraine clearly has a number of strategic objectives. There is an attempt to force the Russians to redeploy forces to try and stop it (and to protect the Russian border as a whole). There is the attempt to politically embarrass Vladimir Putin by showing that he cant protect the very soil of Russia itself. There is an attempt to demonstrate to the world that the Russian Army remains deeply flawed. And there is the objective of destroying Russian forces as they have to be sent to try and stop the Ukrainians offensive. Its one of the reasons that the offensive makes strategic sense for Ukraine—it has a large number of potential benefits, from the battlefield to geopolitics.

However one other possible benefit—or at least strategic goal—has risen to the fore in the last 24 hours. It shows the final hollowness of all the nuclear threats that have been used for years to limit aid to Ukraine. This is actually a profound moment in intellectual thinking—as the Ukrainians are driving a coach and horses (or more obviously a Bradley IFV) directly through almost all earlier assumptions about when and how nuclear weapons will be used. They are invading, taking and possibly holding the sovereign soil of a nuclear power—and in doing so they are upending everyone’s way of thinking about nuclear weapons.

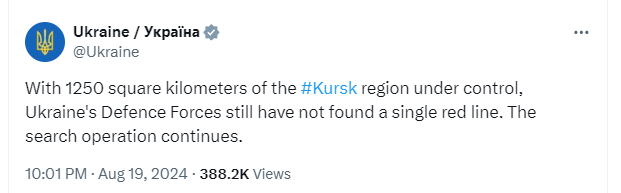

What the Ukrainians have been saying over the last 24 hours to the world, and particularly to the Biden Administration, is that, once and for all, Putin’s nuclear threats are all bark and no bite. The Ukrainians are making that point both seriously and in mockery.

Yesterday, President Zelensky gave a speech to Ukrainian diplomats and the theme was what he wanted them to stress to the world. The number one point was that the diplomats needed to stress the need of Ukraine to be given the ability to use western weapons to make long-range strike in Russia. A copy of the whole transcript of the speech can be found here. Here, however, is how Zelenksy started this section on the need for Ukraine to be freed for more long-range strike—and how its connected to the Kursk Offensive.

So, first – Long-range capabilities.

If our partners lifted all the current restrictions on the use of weapons on Russian territory, we would not need to physically enter particularly the Kursk region to protect our Ukrainian citizens in the border communities and eliminate Russia’s potential for aggression. But for now, we cannot use all the weapons at our disposal and eliminate Russian terrorists where they are.

If Zelensky was being dead serious, the Ukrainian government on twitter took a more humorous and mocking look at the question.

In some ways its predictable—Ukraine has been begging for the ability to receive and use NATO weapons for long-range strike. And as always, particularly from the USA, the Biden administration has been very slow to react. Only now are the first stories emerging that the USA might be willing to deliver JASSMs (US cruise missiles) to Ukraine. Of course even if they do, it will be months and months before they appear.

Yet, at the same time what is surprising is how the Ukrainian Kursk Offensive represents arguably the final nail in the coffin of the pre-Feb 24 2022 assumptions about nuclear weapons use.

We Should Have Had Nuclear War By Now

That might seem a strange thing to say—but the reality is if the war-games and analytical community were right, by this point in this war Putin should have used nuclear weapons. When Putin first launched the full-scale invasion, it was fascinating how often people said he would or was about to use nuclear weapons. This piece published by the Carnegie Endowment’s Christopher Chivvis might have been the most striking—the US, it was said, had run war games and in scores of them, Russia would soon go nuclear.

Amid this escalation, experts can spin out an infinite number of branching scenarios on how this might end. But scores of war games conducted for the U.S. and allied governments and my own experience as the U.S. national intelligence officer for Europe suggest that if we boil it down, there are really only two paths toward ending the war: one, continued escalation, potentially across the nuclear threshold; the other, a bitter peace imposed on a defeated Ukraine that will be extremely hard for the United States and many European allies to swallow.

(Bold is mine)

In one way Chivvis is right—there have been scores of war games (probably hundreds and even thousands) over the decades during which nuclear weapons are used and used regularly—from small level nuclear exchanges to full strategic nuclear exchanges. Indeed, the US in war games has regularly had the Russians using nuclear weapons to secure quite limited strategic objectives.

This possibility of the relatively easy and quick use of nuclear weapons has permeated US thinking about how to respond to the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine and thus how to aid Ukraine. Im sure readers of this substack dont need a long lesson on this, but US aid has always been late to the party with range because of fears of triggering an escalation crisis.

First, in 2022, it seems clear that the US made sure to provide Ukraine with no weapons that could hit Crimea (even though that is legally part of Ukraine) because of escalation fears. Thus, Ukraine was provided HIMARs with only limited range ammunition—no ATACMS. And ideas like the US providing Ukraine with F-16s and JASSMs were definitely off the table.

Indeed, the US went out of its way to assure Putin that the US was not involved in any attacks against Crimea—disavowing knowledge of the October 2022 Ukrainian operation against Sevastopol.

Its a pattern that has been repeated with numerous weapons systems over the last two years. ATACMs, which could have helped immensely in 2022—were only given in late 2023 and in limited quality and range. F-16s are only now appearing over the skies of Ukraine, but they have only limited range systems.

Its part and parcel of how US aiding Ukraine has made what should have been a much shorter war—much longer, more bloody and indecisive. The US has somehow intellectually separated battlefield operations (attacks say within 25 miles of the front lines) from long-range strike (attacks more than 50 miles—and into Russia itself). The Pentagon made that point apparent even the other day when it separated the need for long-range strike from Ukraine’s ability to liberate its territory. Once again, long-range strike was seen as too escalatory by the USA—something that could lead to nuclear weapons usage.

The remarkable thing is the persistence of this idea—in the face of repeated failure of the real-world to align with the assumed world, or the world of war games.

And this is what Ukraine is jumping up and screaming to the USA right now. We (Ukraine) are invading, taking and potentially going to hold and fortify the sovereign territory of a nuclear power—and that nuclear power is not using nuclear weapons against us.

This has always been the last assumed red-line of nuclear weapons usage—and the Ukrainians are marching an invasion force right across it.

What Does it Mean?

In a nutshell, we have built far too many of our policy assumptions for this war (and in general) on nuclear weapons usage. We have made it far more easy than it really is—by running countless war games and building in policy assumptions based on the idea that nuclear weapons usage is not only possible, but in many cases probable.

The war games argument by Chivvis is right in one sense. The war games would have seen the use of Russian nuclear weapons many time over by now—and very possibly the nuclear destruction of the world in a direct Russian-US nuclear war. The problem was that the war games and the assumptions were simply wrong.

The problem therefore is not in the real world—its in those games and assumptions. What the Ukrainians are teaching us is that there is a massive disincentive against the use of nuclear weapons by a nuclear power—even when they are invaded. In the case of Russia, its not as if Putin can simply press a button. The Chinese and the Indians, for two, the two most important states for the continuation of his war, have made it clear that they strongly oppose nuclear weapons usage.

Such a disincentive would be there for any other conflict involving nuclear powers. For instance, and this will have to be developed later, war games that result in a US-China war going nuclear based solely on battlefield issues are almost certainly as wrong as all the war games that had Russia going nuclear over Ukraine. Both the USA and China would have massive disincentives against using nuclear weapons that would almost certainly preclude their use.

Moreover, the way we are thinking about nuclear weapons is not only based on too easy a usage, its perversely constructed that if anything it makes nuclear weapons usage more likely. We are building in assumptions in our thinking that makes war longer and more destructive conventionally—on the assumption that this makes nuclear weapons usage less likely. However, nuclear weapons usage must be seen as less likely than we ever understood—but in lengthening wars we are probably increasing the likelihood of nuclear weapons usage in the end.

We need to rethink the entire way we approach the question of nuclear weapons usage—as Ukraine has and is teaching us. The present way is actually making the world more unsafe and arguably making nuclear weapons usage more likely, not less.