Goobermint has a long history of passing laws that don’t make a difference.

The Continuing Relevance of the Saturday Night Special

Today, reference to a “Saturday Night Special” is rarely heard outside of old films or perhaps among vintage firearms enthusiasts. Rather than a specific make or model, Saturday Night Special is a catch-all term used to refer to a small, cheap, and usually small-caliber handgun often associated with criminality. While hardly mentioned today, these firearms were at one point at the forefront of American gun debates. This post will describe the background of federal restrictions on Saturday Night Specials enacted as part of the Gun Control Act of 1968. It will then discuss why this interesting chapter of American gun law history—which was even discussed in a recent Supreme Court amicus brief—remains relevant to modern observers.

The Gun Control Act of 1968

One of the many policies debated and included in the final version of the Gun Control Act (GCA) of 1968 was a provision intended to ban the importation of Saturday Night Special-type weapons. While the ultimately successful restrictions on interstate firearm purchases and multiple failed gun registration proposals garnered the most vociferous debates, members of Congress from both parties railed against the scourge posed by Saturday Night Special handguns.

Although some opponents would eventually question the logic of the importation ban as well as its impact on gun violence, there appeared to be widespread consensus that these weapons were uniquely dangerous in one way or another. Senator Tydings of Maryland portrayed Saturday Night Special ownership as an urban blight distinct from “good” gun ownership, invoking a then-widely covered Chicago area street gang associated with black nationalism. “It is a far different problem when a member of the Blackstone Rangers gang in a big city purchases a Saturday-night special for $5.50 than when a rural citizen living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland or Idaho or Montana wants to purchase a gun,” Tydings claimed.

Many cited alarming figures from law enforcement sources, such as Sen. Dodd’s claim that “the chief of police of Atlanta, Georgia, said that more than 80 percent of criminal guns confiscated from arrestees were foreign made, cheap $5 or $10 Saturday Night Specials, as they call them.” Others were even more direct in their frightening characterizations, such as Sen. Pastore’s description of Saturday Night Specials as “cheap guns which can be bought by cheap hoodlums to kill people with.” Summarizing the discussions of Saturday Night Specials in his comprehensive legislative history and assessment of the GCA of 1968, Professor Franklin Zimring succinctly noted that

Testimony before Congress suggests three themes associated with these guns: (1) they were cheap and plentiful; (2) they were low-quality and unsafe; (3) they were used in violent crimes. The image projected was not just that of a gun but of a gun and a user class. And the goal implicit in the legislation was to reduce access to guns for high-risk groups by restricting the supply of cheap guns, particularly cheap handguns.

The GCA of 1968 sought to achieve this restriction in supply through § 925(d) of the enacted GCA of 1968, which established new limits on the importation of firearms into the United States. Specifically, § 925(d)(3) allowed importation of a weapon for commercial sale only if the Secretary of the Treasury determined that it “is of a type that does not fall within the definition of a firearm as defined in section 5845(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954 [the revised National Firearms Act] and is generally recognized as particularly suitable or readily adaptable to sporting purposes, excluding surplus military firearms.”

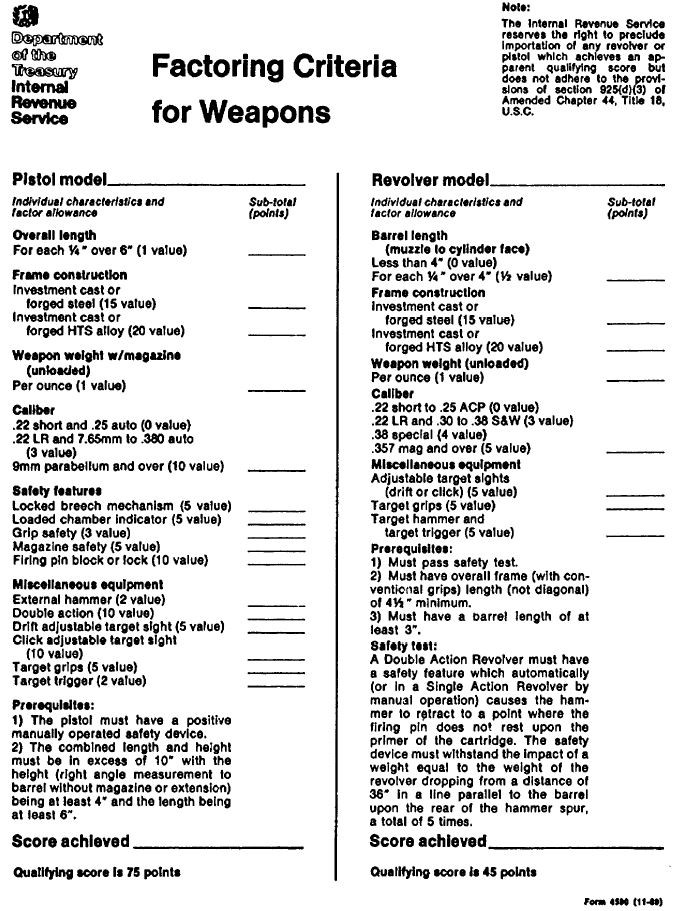

The problem, however, was that the legislation neglected to offer any further definition or even guidance as to what specific characteristics made an imported weapon “particularly suitable for or readily adaptable to sporting purposes.” As such, the IRS, the agency tasked with implementing and administering most of the act’s key provisions, developed its own system of assessment for imported handguns, which it eventually documented in Form 4590, “Factoring Criteria for Weapons” (Zimring p. 165). Factors considered included barrel length, type of construction, weight, and safety features, as well as a minimum size. Potential imports were scored based on these factors; to be eligible for importation, revolvers required a score of 45 or above and automatics a score of 75 or above.

Unsurprisingly, this grading system allowed for arbitrary determinations of importability; comparing two nearly identical handguns, one could be deemed a Saturday Night Special unfit for import and the other deemed “suitable for sporting purposes” simply because of a one-ounce weight difference. Adding to this sense of arbitrariness, the IRS never explained its factoring criteria or the logic behind them in any public documents (Zimring, p. 166). In his assessment of the law several years after its passage, Professor Zimring described “the persistent nondefinition of the key terms in the controlling federal law” as “remarkable;” in his assessment, however, “a major share of the responsibility for this state of affairs belongs to the draftsmen of section 935(d) and to Congress” rather than IRS officials alone (p. 166).

Section 925(d) failed to significantly curb the numbers of Saturday Night Special-type handguns imported into the United States. While observers noted that the IRS’ new import criteria “obviously hit the cheaper foreign handguns the hardest,” handguns of all types continued to enter the United States in large volumes. After briefly dipping in 1969-70, handgun import data show that imports started to exceed pre-1968 volumes by 1971. (Zimring, p. 169).

The law also appears to have contributed to a significant uptick in domestic manufacture of handguns, especially cheaper ones, which helped offset the imports lost to the IRS’ factoring criteria (p. 169-70). Some of this domestic manufacturing was enabled by the fact that § 925(d) did not limit the importation of Saturday Night Special parts, enabling some firms to assemble foreign parts in American production facilities; by 1973, imports of Saturday Night Special parts had risen from a volume of 18,000 parts in 1968 to 568,500 parts, enough to assemble more than 1 million handguns per year (The Saturday Night Special, p. 304). This production would continue for decades, most notably through six Los Angeles-area manufacturers known as “the Ring of Fire” that by 1992 produced 34% of all American-made handguns.

Congressional gun control advocates attempted to pass further legislation to remedy § 925(d), even holding a series of hearings on Saturday Night Specials in fall 1971. Several approaches were considered, including extending the import criteria to domestic handguns or establishing a national testing protocol for domestically produced handguns, but none came close to enactment (Zimring, p. 173).

Continued Relevance

Today, Saturday Night Specials are no longer a hot topic in the national firearms debate. However, the history may nonetheless be relevant to modern firearms law observers for several reasons.

First, the history of Saturday Night Special restrictions raises questions about gun restrictions that appear to target a certain class of gun user. As scholars and advocates seek to emphasize the history of gun control as a tool of racial discrimination, the saga of the Saturday Night Special may serve as a compelling case study. A recent Supreme Court amicus brief filed by Black Guns Matter in support of the petitioners in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen explored this line of argument, describing Saturday Night Special restrictions as “one more thread in [the] deeply discriminatory tapestry” of American gun law history:

This unspoken intent [to exclude ‘unsavory’ groups from owning firearms] seeped into the federal regulation of firearms by 1968, following the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr… [t]he new federal laws targeted so-called “Saturday Night Specials,” which were small affordable handguns popularized in African American and minority communities. (citation omitted)

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the “Saturday night special” is emphasized because it is cheap and is being sold to a particular class of people.’” (citation omitted).

How such arguments might factor into how courts assess Second Amendment cases remains an open question. However, in recent years several Justices have authored opinions expressing an interest in the discriminatory history of some of the laws under review even when it is unclear how that history is relevant under existing doctrine, such as Justice Thomas’ concurrence in Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky (recounting the historical links between 20th century eugenicists and early abortion advocates in a case over new abortion restrictions) or Justice Alito’s concurrence in Espinoza v. Montana (describing the history of anti-Catholic sentiment and 19th century Nativism in an education voucher case). Given this trend, it seems quite possible that one or more Justices will incorporate some discussion of discriminatory firearms laws into an opinion in Bruen.

Second, the Saturday Night Special saga illustrates the difficulties of statutorily defining a nebulous style of firearm, particularly when that style of firearm carries with it a range of strong connotations. Disagreement over statutory definitions continues to this day, most notably with respect to firearms classified as “assault weapons.” Assault weapons have for some time been a lightning rod in gun control debates, and like the Saturday Night Special, these firearms have become a key target for gun control advocates who view them as a uniquely dangerous class of firearm. Also like the Saturday Night Special, defining what exactly constitutes an assault weapon has been the subject of fierce debate that carries important implications.

The 1994 assault weapons ban, which expired in 2004, defined assault weapons as a “semiautomatic rifle that has an ability to accept a detachable box magazine” and at least two of five listed features including “a folding or telescoping stock,” “a pistol grip that protrudes conspicuously beneath the action of the weapon,” a threaded barrel or flash suppressor, and more. Like the IRS Factoring Criteria for Saturday Night Specials, however, these criteria resulted in arguably arbitrary classifications, and minor design modifications by manufacturers could render otherwise prohibited weapons permissible. Furthermore, critics have argued that many of the features that legally render a firearm an assault weapon are “cosmetic” in nature and that there is little meaningful difference between weapons designated as assault weapons and other semi-automatic rifles.

Third, the history of Saturday Night Special regulation illustrates the perils of enacting restrictions focused on a certain type of firearm without a rational articulation of why that type warrants special regulation. The core premise that Saturday Night Specials were more dangerous or lethal than other handguns does not bear much scrutiny.

While they may have been concealable, so were many other more expensive handguns; furthermore, other key characteristics such as their low caliber, cheap construction, and lack of reliability could reasonably be said to make these guns less lethal, not more. As Professor Zimring concluded, “the attack against cheap imported handguns was powerful but pitifully underinclusive.

Handguns retailing for under $50 are a major public safety problem—but so are those retailing for over $50.” (p. 166). Another contemporary assessment from journalist Robert Sherrill, himself a vocal gun control proponent, was even more scathing, predicting that “history will not support the snooty caste-consciousness in gun traffic. All guns are terrible, no doubt, but one kind no more than others” (The Saturday Night Special, p. 321).

Because § 925(d) was never the subject of any high-profile litigation, such criticism of the rationale behind it was largely limited to observers like Zimring and Sherrill rather than the courts. Post-Heller, however, the bar for such a rationale to survive judicial scrutiny appears to be even higher. While the poor drafting and muddled rationale of § 925(d) might make the provision more questionable today today, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California’s recent decision in Miller v. Bonta raises questions about whether policy-makers can enact blanket restrictions on certain types of commonly-owned guns at all. That decision, which overturned California’s 30-year-old ban on assault weapons, held that governments bear the burden of proving that a type of firearm is sufficiently “uncommon and dangerous” to warrant restriction, before which such firearms are presumptively lawful to own.

The court went on to hold not only that California’s proffered evidence failed to demonstrate that assault weapons were disproportionately used in crime, but that “more importantly, disproportionality is not a constitutional test.” Should Miller become widely-cited precedent, restrictions on a type of weapon predicated on disproportionate use in crime may soon seem as anachronistic as the initial furor over Saturday Night Specials.