BLUF

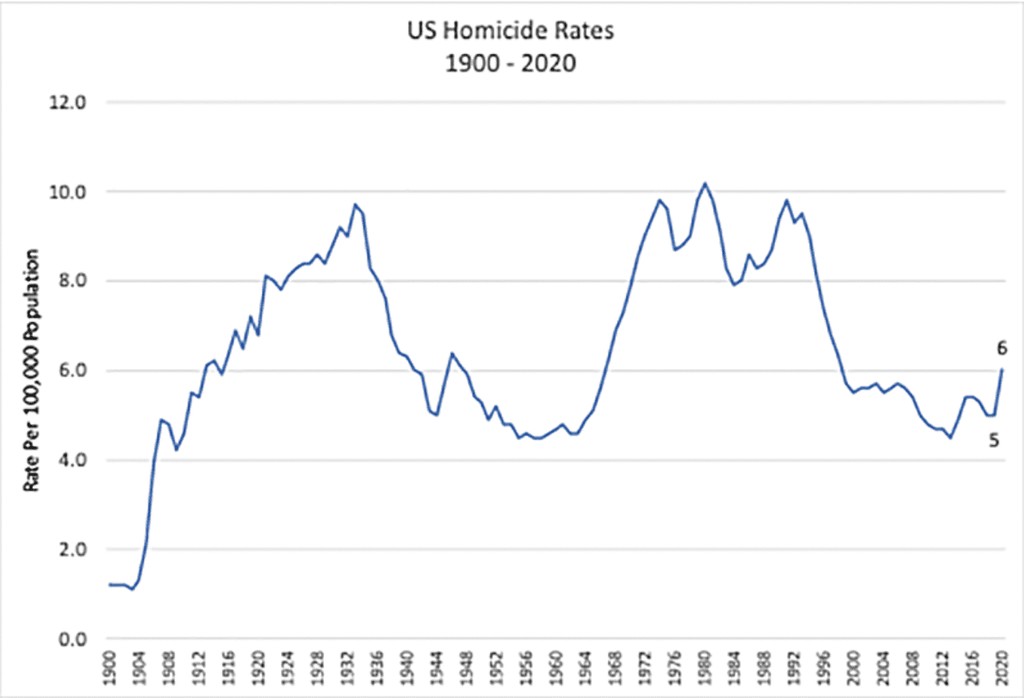

Gun-control advocates predict increases in murders with constitutional carry, but the data says otherwise. Self-defense is a natural right. That right can be restricted when there is a strong reason to do so; for example, people confined in prisons are not allowed to possess firearms. But, the opponents of constitutional carry across society have not met their burden of proof.

The Statistical Truth About the Impact of Constitutional Carry

When it becomes clear that a popular change in state law does something fundamentally good for citizens’ freedom without doing harm, it becomes much easier to get legislators to do the right thing. This is part of the reason for the quick spread of constitutional-carry laws, which now cover half of the states, as of press time. (A state is “constitutional carry” if a law-abiding adult who can legally possess a handgun does not need a permit to carry that handgun concealed for lawful protection.)

Another part of the reason for the fast spread of constitutional-carry legislation is the NRA Institute for Legislative Action’s (ILA) team, which has worked across America to bring the facts to state legislators. They have been so effective that a majority of state legislators in Alabama, Georgia, Indiana and Ohio most-recently opted to get their state’s bureaucracies out of the way of their law-abiding citizens’ Second Amendment rights.

An underlying reason this has been an effective push is the basic fact that law-abiding American citizens are not problems that needs to be solved. Despite what the Biden administration argues, armed citizens help to keep individuals safer. Nevertheless, each time a constitutional-carry law comes up for debate, gun-control groups argue that getting the government out of the concealed-carry-license business will result in “Wild West-style shootouts” on the streets. But each time these laws pass, the data clearly shows that doesn’t happen.

This has been a big change from a few decades ago when Vermont was the sole state with constitutional carry. The term “constitutional carry” comes from legal history; when the Second Amendment was adopted in 1791, constitutional carry—either open or concealed—was lawful in every state.

Still, as more and more states return to the original understanding of the right to bear arms, opponents warn that constitutional carry (or “permitless carry”) will cause murder rates to increase; for example, Eugenio Weigend, director of the Gun Violence Prevention program at the Center for American Progress, says that constitutional carry will “raise some confrontations in some places, further escalating violence to reach lethal levels.” Michael Bloomberg’s anti-gun group Everytown for Gun Safety says states that have moved toward constitutional carry are “abandoning core public safety standards.”

While Vermont has long had constitutional carry, thanks to the 1903 state supreme court decision State v. Rosenthal, the move toward constitutional carry in the 21st century started with Alaska in 2003.

In this article, we present the data about what actually happened when states adopted constitutional carry. The data comes from a report co-written by Alexander Adams and Colorado State University Professor Youngsung Kim. (The data and code are available at: https://github.com/K-Alexander-Adams/Am1st)

Except for Vermont, all the states that currently have constitutional carry already had “shall-issue” licensing systems for concealed carry. That is, applications for concealed-carry permits could not be denied simply because the licensing official did not like citizens carrying firearms.

So, why did the NRA work for constitutional carry in those states? Because even a fairly administered shall-issue system can take weeks or months for a license to be issued. The delays can leave the innocent defenseless for too long; this is especially true for victims of stalkers and for people fleeing domestic violence. The same is true when civil order breaks down, such as during riots or natural disasters—times when law enforcement is often overwhelmed. Some licensing offices, for example, shut down or slowed down during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even when a state statute sets up a fair process for licensing, local governments can find ways to manipulate the system to delay applications. This has been a long-standing problem in Denver, and is one reason why civil-rights activists are fighting for constitutional carry in Colorado.

A second reason for constitutional carry is cost. To some people, spending a few hundred dollars for fees, fingerprints and so on is no big deal. But for lower-income people, the financial barrier of a licensing system can be severe to prohibitive. Constitutional carry also eliminates the possibility of bias against any racial, gender or socio-economic groups in the permitting process.

Even in constitutional-carry states, many people still choose to obtain permits. Permits make it easier to carry in other states when traveling, because many states have laws that recognize the permits issued by some or all other states. Depending on state law, a permit may allow carrying in some places where constitutional carry is not allowed.

How Does Constitutional Carry Impact Crime?

How can we determine the effects of constitutional carry? One approach would be to just compare current crime rates in states with and without constitutional carry; for example, Vermont, with constitutional carry, has much less crime than neighboring New York, which does not. The same is true for Utah versus Colorado. But skeptics would accurately point out that other differences between the states could account for the differences in crime rates. Portions of New York, for example, are more urbanized than Vermont.

Further, because crime rates change over time, looking at several years is more revealing than just a single year.

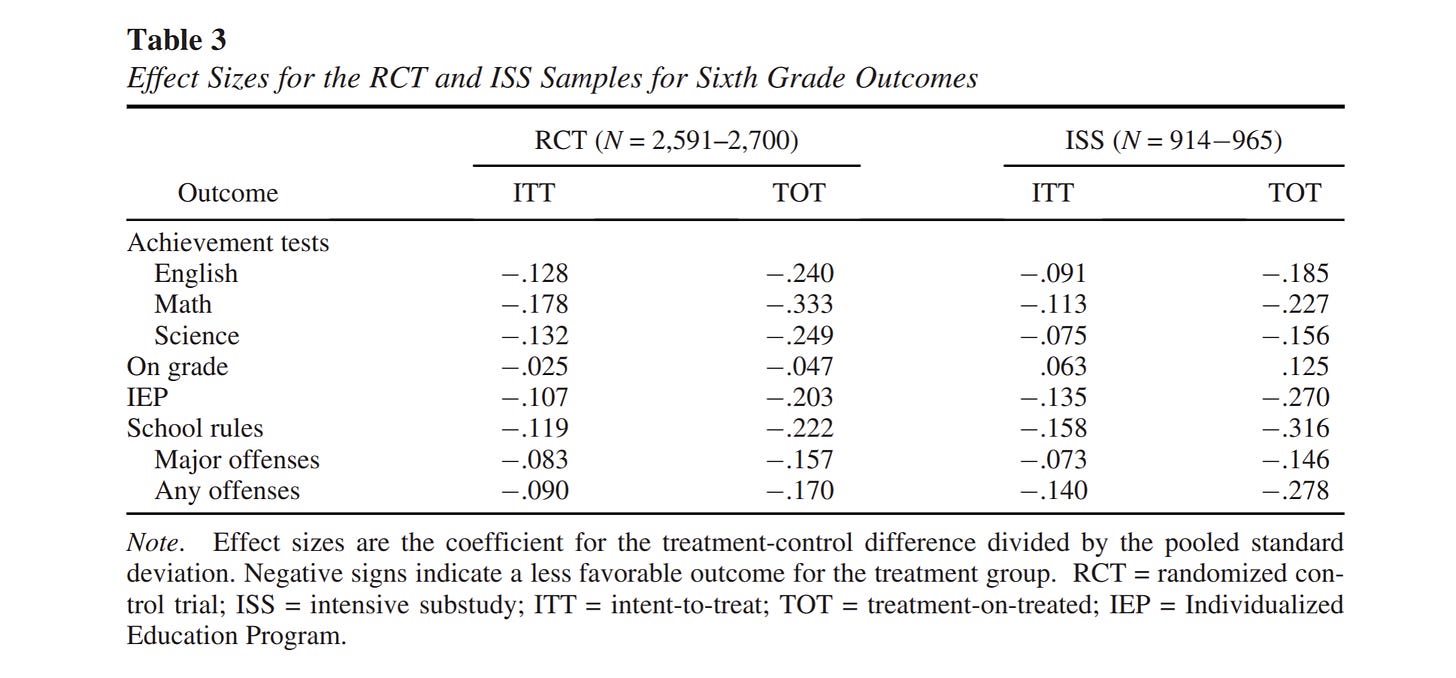

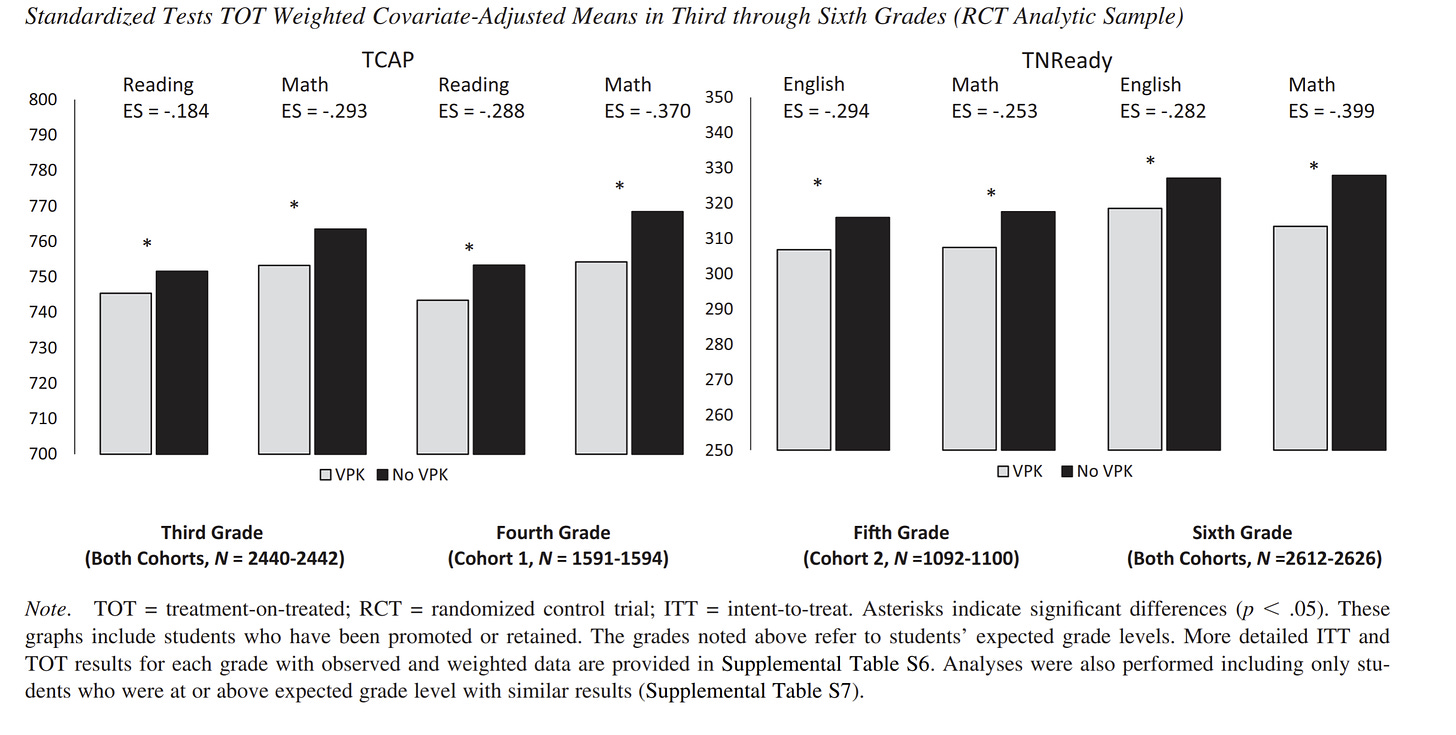

To get answers, Adams and Kim studied all 50 states and the District of Columbia from 1980 to 2018. Their study also accounted for 30 control variables—that is, factors other than constitutional carry that might raise or lower a state’s crime rate. The control variables included population density, alcohol consumption, poverty rates, unemployment rates, the Fryer crack-cocaine index, incarceration rates, age cohorts in five-year blocks from age 15 to over 65 years of age, police per capita, other gun control (such as “assault-weapons” bans), racial variables and more.

To show how important it is to consider control variables, we will first show you the results without them, and then the results with the control variables included.

Here is a short explanation on how to read the tables. Suppose you flipped a coin 100 times, and 65 of those times, it came up heads. Does that prove the coin was biased (unevenly weighted), or could the results just be random chance? In social science, the probability that the result was not due to chance is called “statistical significance.” In the tables, if there is less than a 1% chance the result is due to chance, the result has three asterisks. If the probability that a result is random is less than 5%, there are two asterisks. If less than 10%, there is one asterisk. Traditionally, statisticians use the 5% cut-off to call something “statistically significant,” but they also report results for 1% and 10%. We do the same.

Continue reading “”