‘You can’t stop the signal..’

Winnipeg Police Seize AR15 and Glock with 3D Printed Receivers

‘You can’t stop the signal..’

Winnipeg Police Seize AR15 and Glock with 3D Printed Receivers

Changing Your Carry Depending on Your Environment

Change. We’re in the middle of it. Millions of people have purchased their first guns over the last few months. Riots, looting, theft, attacks, murders. We see it daily on the news. Smart people know, or have just realized, that the police can’t be everywhere, and it highly unlikely they will be close when you are attacked.

You are your own first responder. Are you prepared?

Trainers across the country are being flooded with calls asking for private lessons. That’s good.

Let me explain something that’s not obvious to new gun owners, but which can make a big difference in your ability to have a self-defense handgun with you. It requires change. Specifically, it means you have to change your handgun as conditions change.

I’ve been carrying a pistol since about 1976. Big guns and small guns, big calibers and small calibers, double stack and single stack, short barrels and longish barrels, revolvers and autoloaders. Why so many types?

There is no one handgun that works for every situation.

You have many types of footwear so that you can have the right function for each activity. Tennis shoes, dress shoes, casual shoes, hunting boots, rubber boots, slippers, etc.

Once you get into carrying you quickly realize the need for various sizes of handguns.

Let me give examples of what I have carried, using just one gun manufacturer. I have carried Springfield Armory pistols for many years. I recently bought the XDm 4.5-inch barrel model in 10mm. Why? Because sometimes I’m in the woods where bears, mountain lions, and wolves live. I really like the idea of having 15 rounds in the magazine of special (deep-penetrating) 10mm ammo with me. It’s a full-size pistol, and it is not light weight when fully loaded. That’s okay because I use a good gun belt and a good holster to handle the weight.

But that’s not what I would carry in most concealed carry situations. For that, I often have opted for two Springfields. The XDs single stack is a dream. Slim, great trigger, and you can get a 10-round mag. Honestly, it’s just hard to go wrong there. I can conceal it when wearing almost anything, especially when I use a tuckable holster. I’ll admit, though, that I like the idea of more ammo, so I have more often carried my XDm 3.8 Compact (now discontinued). The logical replacement for that pistol is the even smaller Hellcat in 9mm, and I’d use the 13-round mag as standard. It’s incredibly small and easy to carry.

When I’m going to spend several days at a shooting school, I’ll opt for a full-size 9mm. Easier to shoot. Ammo is fairly inexpensive. I would go for the XD-M Elite 4.5 and a bag full of magazines.

Now, if you are into style, you might just want to add a sweet 1911 to the mix. Every serious handgunner needs at least one, and after the first magazine of ammo, you’ll fall in love with the trigger. If I could have only one 1911 from the Springfield line, I just might go for the new Ronin Operator in 9mm.

You match the gun to the situation. Where are you carrying? What kind of clothes? Open carry or concealed carry? Just a cover garment or deep concealment? What’s your body type? Pocket carry?

Experienced gun folks know we must change guns from time to time. This example was just using one brand. You can mix and match, of course. You might want to have a revolver in the mix. Just don’t get locked into the idea that now you have “the” gun you need.

Oh, and put serious time and money (!) into the best training you can afford. A shiny new gun will never replace the vital skills you get from serious instruction.

Be safe. Be kind. Stay dangerous. ~ Tom

Tom Gresham

Meet The USAF AR Style Survival Gun – the GAU-5A

While in the skies above, pilots in modern military aircraft often have no shortage of weapons literally at their fingertips, but a pilot who finds himself on the ground behind enemy lines is worse than a bird with clipped wings. During the First and Second World Wars, the best a pilot could have in the way of a personal defense weapon or survival gun was a sidearm. Later, during the early stages of the Cold War, the United States Air Force relied on what were some rather odd survival weapons. Let’s take a look at the various survival rifles over the years, leading up to the GAU-5A.

These included the M4 Survival Rifle, a .22 caliber bolt-action rifle that was developed by Harrington & Richardson from their commercial M265 sporting rifle. It featured a sheet metal frame with a telescoping wire buttstock. It was, simply put, “better than nothing,” but it was mainly intended as a survival gun to allow a downed aircrew to forage wild game for food rather than to deal with a hostile enemy.

The M6 Air Crew Survival Weapon was another weapon that was developed by the Ithaca Gun Company and the Springfield Armory as rifle/shotgun designed for pilots who flew over the Arctic and other uninhabited areas. Again, it was more for foraging than defending, which prompted the Air Force to explore other options.

From that came the AR-5, a bolt action takedown rifle that was still chambered for the .22 Hornet cartridge, and that led to the ArmaLite AR-7 Explorer, a semi-automatic firearm in .22 Long Rifle caliber that was developed by Eugene Stoner. Introduced in 1959 it is still in use today as an aircrew as well as civilian survival gun. While a generally reliable firearm – so much so that it has been adopted around the world, including by the Israeli Air Force — the AR-7 was lacking in stopping power.

Hence the Air Force turned to another of Stoner’s designs – namely the AR-15 platform that was adopted by the U.S. military as the M-16. The Air Force had been the first branch of the service to adopt the AR-15. They soon decided to adopt a carbine version with a 10.5-inch barrel and 4-inch flash hider. The Air Force, unlike the Army or Marines, had no naming convention for small arms and simply put the weapon in its aircraft gun category. Thus was born the GAU-5/A. It became the standard issue weapon for Security Police dog handlers and other specialized personnel. GA was meant to denote an automatic gun while U was for “unit” hence: “Gun, Automatic, Unit.”

Where it gets confusing is that the U.S. Army adopted a nearly identical version of the weapon, which Colt –then the sole maker of the CAR-15 line of military firearms – called the XM177E1. Both versions select fire with semi- and full-automatic fire modes and each was officially classified by Colt as submachine guns. This was despite the fact that these still were chambered in the .223 Remington cartridge rather than a pistol cartridge that is typically used in submachine guns

The Air Force’s GAU-5 was updated as the GUU-5/P, which featured a longer 14.5-inch barrel with a 1-in-12 twist. Otherwise, the firearm kept the modular design that had made the CAR-15s popular with the military.

During the Vietnam War, the Air Force also developed the Model 608 CAR-15 Survival Rifle, which was meant for use by downed aircrews. This model, which resembled the Colt Commando, also featured a 10-inch barrel. Its modular design allowed it to be broken down into two subassemblies and stowed in a seat pack.

In recent years the Air Force has again considered the benefits of a modular takedown weapon. This has included the GAU-5A. The new version is a modified M-4 carbine, the same type that is currently used by the U.S. Army and United States Marine Corps, as well as Air Force security personnel. This version is a modified “takedown”. It can break into two major pieces for storage within an aircraft that includes the ACES II ejection seat.

These new versions were designed by the Air Force Gunsmith Shop, which was first formed in 1958 to repair and refurbish small arms for the Air Force. The crafty Airmen at the Gunsmith Shop have made numerous modifications to the M4. One modification was replacing the standard 14.5-inch barrel with a 12.5-inch to reduce the overall length. This was done in part to ensure that it can fit in the aforementioned ejection seat. That is no ordinary barrel but rather the specialized Cry Havoc Tactical Quick Release Barrel (QRB) kit, which allows the gun to neatly break into two pieces.

The weapon weighs less than seven pounds and can be put together in just about 30 seconds. That might still be more time than most pilots would like to spend on the ground in hostile territory. Still, it will give those flyers some much-appreciated firepower.

Unlike the original survival weapons that were primarily only good for foraging, the GAU-5A fires the high-velocity 5.56mm round. So it can take down large game. More importantly, it can take down any enemy soldier who finds a pilot with the unfortunate luck of being shot down.

To date, the Air Force’s Gunsmith Shop has built and shipped out some 2,700 of the new weapons. The cost to develop the system was around $2.6 million. So the GAU-5A price tag is less than $1,000 or what a reasonably decent civilian AR-15 would cost.

This Historic Colt 1911 Pistol Carried at Iwo Jima Is About to Go Up for Auction

Rock Island Auction Company will soon be taking bids for the 1911 Colt .45 automatic pistol, and other kit, carried by a decorated Marine combat photographer during the Battle of Iwo Jima in World War II.

Following the recent 75th anniversary of Iwo Jima — a brutal battle that stretched from February 19 to March 26, 1945 — the Rock Island, Illinois, auction house will hold its Premier Firearms Auction #79, featuring 2,500 lots of firearms and related items June 5-7.

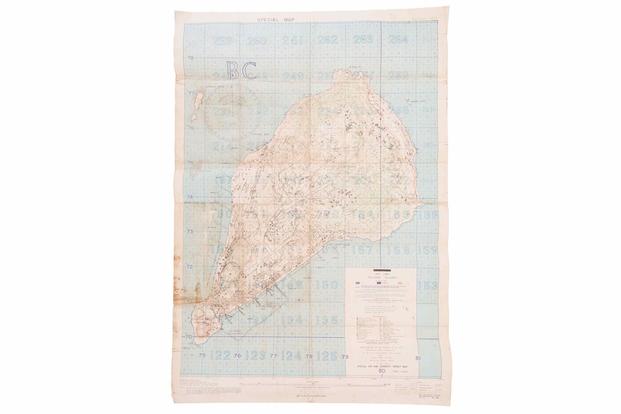

One of the lots, number 1516, will feature items such as the sidearm, pistol belt rig and rare Iwo Jima battle map that belonged to Marine Sgt. Arthur J. Kiely Jr., who passed away in 2005, according to a recent news release from the auction company.

Kiely joined the Marine Corps in 1943 and served as a combat photographer, taking pictures under heavy enemy fire on island engagements such as Iwo, the release states.

Kiely’s Colt 1911 was originally shipped to the Marine Corps in 1917 and features “85% of its original blue finish showing a mixed brown and gray patina on the grip straps and trigger guard, bright edge wear, and mild spotting and handling marks overall,” according to the auction’s website.

The pistol’s refinished grips have some “dents and tool marks on the screws” and the “modified, refinished replacement trigger sticks a bit,” the website states.

Lessons Learned From Col. Jeff Cooper

In Col. Jeff Cooper’s armory, sitting with the legend himself, I suffered a negligent discharge—with words, not bullets.

It was bad enough that I committed a grievous English error, because I had been reading Cooper’s books since the late 60s, riding my Schwinn Varsity a couple of miles from my house to the library in Clovis, Calif. When I bought my first pistol in 1987, it was a Colt 1911 in .45 ACP, just like the colonel carried.

In 1992, working as a TV reporter, I somehow convinced my station to do a story about Gunsite Academy. Bill Jeans, rangemaster at the time, ushered me into the inner sanctum.

Cooper was equally renowned for his precision with language, and he did not tolerate incompetence. In the armory, I asked him about his personal philosophy of self-defense.

He opened his mouth, but no sound came out. It took almost two agonizing seconds—I timed it because I still have the video—for him to speak.

“I am not sure of that sentence, ‘A personal philosophy…’ What’s an impersonal philosophy?”

At that moment, I felt as tall as a .22 Long Rifle cartridge. But like all hard lessons, it stuck. Words are like ammo. Don’t spray and pray.

I continued to learn from the colonel. I bought a used Tikka Scout, a .308 Win. with a Leupold 2.5X scope in front of the action. In his book, “To Ride, Shoot Straight and Speak the Truth,” Cooper praises this setup: “This forward mount, properly used and understood, is the fastest sighting arrangement available to the rifleman.”

In 2017, on my friend’s ranch in central California, I went pig hunting with Col. Craig Boddington. I had been reading his articles for years, and I’d also watched him on TV. I didn’t want to screw up in front of him or my friend, Anthony Lombardo, even though Tony is used to it. So, of course, I missed shot after shot.

In the Jeep, I got pretty lonely in the back when the discussion focused on my rifle. There were two skeptics in the front seats who had me outgunned.

Other shooters disagree with the scout concept, or have abandoned the idea, including the veteran hunter who sold me his Tikka. But an unconventional scope mount wasn’t causing me to jerk the trigger. Surprise Break, I heard Cooper whisper. Surprise Break.

Then I saw three pigs. Not trophies, but we were hunting for meat anyway. I picked the largest of the trio. My handload—45.5 grains of Varget under a Nosler 150-grain E-Tip—staggered the big one. Boddington held off until I connected, then joined me with his .270 Winchester as we cleaned up.

“Great shooting, partner!” Boddington is so polite that I think he was just being kind, but I gratefully accepted the compliment.

I also have a forward-mounted scope on a 30-40 Krag that once belonged to my beloved Uncle Harry. Like the Tikka, this rifle isn’t a true Scout. But Col. Cooper shared my admiration for the Krag, and I hope he would approve. When we rescue vintage guns from the back of our safes, we honor the past. The true innovators, such as Jeff Cooper, live on.

My video of the colonel’s interview includes his famous mindset lecture. I shared it with some Gunsite grads. Wyoming’s Ed Cassidy said it best: “I miss him every day.”

The Fire Control Unit X03

Fire Control Unit first started its work with the XO1 PDW conversion for the SIG P320. Being a drop-in enhancement system for the pistol, much like the CAA Micro Conversion Kit. They’re now working on the X03 project by taking the fire control unit of the SIG and dropping it into an AR platform.

Meet the gun safety instructor holding ‘office hours’ on Zoom

Gun rights advocates are promoting safety training in response to record-breaking numbers of arms sales amid Covid-19

On a recent afternoon in San Jose, California, Chuck Rossi held up his AR-15 in front of his computer camera, talking through how to hold the weapon safely, and how to load it with ammunition.

“AR-15s are modular. They’re like Legos for men,” Rossi said. The man on the other side of the Zoom call chuckled.

Rossi is an activist turned safety instructor, one of the many gun owners across the country who are using Zoom or social media to teach new gun owners how to use their weapons.

The coronavirus pandemic has driven record-breaking numbers of gun sales in the United States, as gun sellers have succeeded in being categorized as “essential businesses”. At least anecdotally, many of the millions of guns sold during the pandemic have gone to first-time gun buyers, sparking concerns about potential increases in domestic violence, gun accidents and child gun deaths. Gun control advocates say the panic-buying during a time of anxiety, uncertainty and economic distress has also made gun suicide a particular concern.

In response, gun rights advocates have focused on safety training, with some offering free sessions to make sure new gun owners understand how to operate their weapons – and feel welcomed to the gun community.

Rossi was an early Facebook employee who left the company in 2018, and still lives in San Jose. He co-founded Open Source Defense, a Silicon Valley gun rights group. The group’s founders live across the country, but many of them are current or former tech workers. Between 20% and 30% of Americans say they personally own a gun, a number that has fallen for decades, and the group aims to grow the base of American gun owners by being friendly, digitally savvy and “zero percent” focused on culture wars. Zoom “office hours” for new owners is one of their initiatives.

When he signed up for a Zoom gun safety session, one new gun owner, a 40-year-old tech company worker from San Jose, said he expected he would be chatting with “some hillbilly NRA guy”.

“Is he even going to be nice to me?” the tech worker, who is black, wondered. Instead he got Rossi, who works in the same industry and lives in the same town. Just a few years ago, the new gun owner, who asked that his name not be used, said he was someone who had believed that AR-15s should be banned.

In early March, as concerns about coronavirus grew, his company told employees not to worry, that “the government has it under control, there’s going to be a vaccine.” Then he went to grocery store, “and there was nothing” so he had to go to his parent’s house to get toilet paper.

He starting thinking about stories of civil unrest during the Los Angeles riots or Hurricane Katrina and said he worried about desperate people, hungry people, who might see homes in his nice San Jose neighborhood as soft targets.

“People take from those who have,” he said. How likely was it that he would ever be a target? “One in a million,” he said. “I consider it an extreme impossibility. But why not be prepared?” In mid-March he went to buy self-defense weapons: a handgun and, because shotguns were sold out, an AR-15, which retails for about $1,000.

The new gun owner’s parents were appalled, and worried about the safety of his young children, ages three and one. His mother tried to get his brother to intervene. Instead, his brother bought himself three guns and thousands of rounds of ammunition.

The new gun buyer said the Zoom session was part of his attempt to be responsible. Rossi, hefting his own high-end AR-15, recapped the principles of gun safety: always keep the weapon’s muzzle pointed in a safe direction. Keep your finger off the trigger until you’re ready to fire. Be aware of what might be behind the target you’re shooting at. Treat every gun as if it’s loaded.

They did some troubleshooting: what should he do if an ammunition round got jammed inside his gun? How long would his military-surplus ammo be usable? Ammo didn’t go bad, Rossi said. He was still “shooting rounds” from the second world war and “surplus from the Korean war”.

While “white Americans tend to be more vocal about their gun ownership”, the new owner said, being a black gun owner didn’t feel special. But it came with different concerns. He was more afraid a police officer might shoot him than that someone else might attack him on the street; he would “never” carry a gun in public.

If he ever had to call the police to his home, he said, he would emphasize: “The black guy with the gun is the homeowner.” Owning guns had already shifted some of his political opinions. He said he still supported limits on larger-capacity ammunition magazines. But when he bought his guns, he said, he had to wait 10 days to get them. “That was an eternity to me,” he said. “Are these really common sense gun laws?”

Rossi was encouraged to hear this, and said he’d try to persuade the new gun owner about why he actually needed larger-capacity magazines next. The two men made a plan to go shooting in person as soon as possible.

From my experience, and from some others I worked with who use guns for the most extreme circumstances, if you go with dot sights on your self defense handguns, you go totally dot sight on them.

Between irons and dots, there’s enough difference on how the gun has to be presented to acquire your sight picture, that switching back and forth will cause you to take extra time to get on target.

And since time is of the essence if you need to use a gun to defend yourself, you can’t afford to waste any chasing the dot down.

So, it’s one or the other. Don’t mix them for your self defense inventory.

A good reasonable argument. I might make the choice between a shotgun and a rifle moot by having both, but that’s just me.

Three Firearms for Emergency Preparation

A firearm that is kept specifically for self-defense is akin to a fire extinguisher: it is life-saving emergency equipment maintained for rapid and unexpected deployment to mitigate a threat. A safe home should have both tools readily available to authorized users, and both should be maintained regularly. For those of us that are firearms and shooting enthusiasts, guns become more than just life-saving equipment; they may be our hobby or even integral to our lifestyle or work. Regardless, let us remember the most essential role of the firearm.

During this current pandemic, which has been declared a national emergency, we are experiencing something rather unique in the lifetimes of most currently living. While civility has, for the most part, been maintained thus far, people are scared. This is manifest by the current panic buying of firearms and ammunition, among many other commodities. First-time gun buyers have stripped the shelves bare of firearms inventory and ammo at a rate we have not witnessed in a while. This current situation has served as a reminder that our stability in firearms supply is as delicate as our supply in any other commodity, perhaps even less so.

The answer to such periods of high demand and low supply should be obvious: we should be sure to have stocked what we need before such catastrophes happen. What we need to keep on hand will vary extensively from one individual to another. Most non-gun enthusiasts are probably well enough served by having a pistol and a box of ammo in the drawer. For those of us that consider firearms an essential part of our preparation, however, we are looking at more equipment than that.

How much is enough?

How many guns and how much ammo should you have on hand? This is an endless debate. If you are relatively new to firearms, or if perhaps you are a hobby shooter but not yet squared away in regards to a dedicated arsenal of personal protection, you might be trying to figure out where to start. Obviously, having a single pistol and a box of ammo may well be all you ever need, but those who are motivated to prepare seek to equip themselves beyond this. While we would all love to have dozens of guns and tens of thousands of rounds of ammo on hand for our preparation and range entertainment, this is not realistic for most, nor necessary.

3-Gun Emergency Setup

I truly believe in a three-gun setup for emergency preparation as a starting point. This is a realistic place to begin and is more obtainable than having a huge safe full of guns. And it will likely fill all self-defense needs for those who never go beyond these three guns. What I suggest is as follows:

#1. Primary Defensive Pistol

First priority: a primary defensive pistol, preferably a full-size service pistol or compact version thereof. Think Glock 17 or Glock 19, Smith and Wesson M&P full size or compact, Sig P320 full size or compact, etc… A double-stack auto loader chambered in 9mm is hard to beat for most. This gun can be carried and is formidable enough to serve as a good home defense pistol as well. While a dedicated concealed carrier may need a smaller option as well to provide deep concealment, the full-size or compact pistol serves as an ideal go-to handgun option.

#2. Duplicate Primary Pistol

Second Priority: A duplicate of your primary pistol. That’s right, a backup to this primary defensive weapon. Perhaps your primary is a full size, and the secondary is the same gun, but the compact version. This would work well as it allows magazine compatibility between the two. A backup to your primary pistol is in order to be truly prepared.

#3. Defensive Long Gun

Third Priority: A defensive long gun. Rifle or shotgun, the choice is yours. The bottom line is that a long gun brings far greater ballistic capability to a fight. So having a dedicated defensive long gun that is ready for home defense makes good sense.

Simplify Your Defensive Arsenal

If you are a new firearms owner and want to acquire a minimum defensive arsenal that will serve your needs, these three weapons should do so quite well. Even if you are a gun person, and perhaps you shoot as a hobby, but you have found that your selection of weaponry is disorganized, then settling on these three options and prioritizing them as your go-to defensive weapons is in order.

Ammo and Magazines

With the selection of these three weapons, you realistically have to stock only two forms of ammunition, and two kinds of magazines (unless your selected long gun is a tube fed weapon such as a shotgun). This will greatly simplify your preparedness for such emergencies, like the one we are currently witnessing, in which firearms and ammunition is now hard to come by due to panic buying. Having only a single pistol caliber and a single long gun cartridge to stock for your defensive purposes will make maintaining a needed supply of ammunition easier. Even if you are a gun collector, with multiple pistols in all of the various chamberings, settle on your primary platform and be sure you have enough magazines and ammunition always on hand for that particular platform.

How much ammo is enough?

Everyone will have a different answer. But I will propose one that I believe is more realistic for most people who live within a budget that must be spread across not only firearms but all other preparation concerns as well. My suggestion for an initial goal to work towards is to have 1,000 rounds on hand for your defensive handguns, and 1,000 rounds on hand for a defensive rifle. Premium defensive ammunition is expensive. So having perhaps 200 rounds of premium hollow point ammo for each is in order. You can back this up with ball ammo. This is not ideal for defensive use, but a lot better than no ammo in a crisis. Always keep your defensive firearms loaded with the premium ammunition. If your long gun is a shotgun, having 200 rounds of buckshot on hand is in order. 1000 rounds of buckshot is quite bulky and expensive.

These weapons and ammunition are for emergency use, be it everyday self-defense or for the event of an extended emergency. If budget allows, keeping a year’s supply of practice ammo on hand makes sense as well. But defensive ammunition is first priority, of course.

Keeping Parts on Hand

Want to go a step further? Maintaining a parts kit with the most likely parts that break for your handguns makes sense. For a long gun, you can do the same. Keep a spare bolt carrier group for an AR15 on hand. This allows you to drop in a replacement for any of the most likely issues.

Prioritize this small, yet capable, assemblage of weaponry for the next emergency. This will give you confidence in at least that part of your preparedness.

Five Key Features of a Good Pocket Pistol

Pocket pistols, or sometimes called backup guns (BUG), are all over the place and are generally really popular. I think there are a couple of reasons for this. They are usually pretty cheap, comparatively speaking, running around $350 or less for the most part. They are also really easy to carry. So easy to carry that people usually don’t have to change anything about how they dress or what they do to be able to carry it. We still rely on these guns to save our lives, though, so here are some things to look for next time you are on the hunt for a new blaster gat to stuff in your pocket.

Sights

Not all pistol sights are created equal, and that is really true when we start talking about pocket guns. Some of them barely even have “sights.” Looking at the Ruger LCP, and almost everyone else who makes a pocket pistol. For most of the pocket-sized guns that do have sights, they are small, and non-adjustable and cannot be changed. If your particular sample of said gun doesn’t shoot to the sights, oh well, too bad. However, there are some exceptions. Seek out those exceptions, and at least give them some consideration. Just because these guns are small doesn’t mean the things we may need them to do are equally small. Having mostly proper sights that can be seen, are adjustable if needed, or can be changed to something closer to our preference, can be a big deal.

Reliable

As guns get smaller, the amount of reliability we expect from them also gets smaller. Or at least it seems that way. Getting an itty bitty machine to run reliably is a difficult job, and sometimes the manufacturers miss. However, we really need these guns to work well because they really only have one purpose, and there are no second chances sometimes. Unfortunately, we can’t tell if a gun will be reliable until after we have bought it and invested enough resources of time and ammunition to find out. It is the way the world is, though.

Manageable Trigger

Most triggers on full-size handguns are manageable. They may not all be to our personal taste, but someone who has a decent grasp of skill can make it work in a pinch. Triggers on pocket guns are not always the same. Again, it comes down to the size of the gun, and getting a decent trigger in that package is apparently a tough thing to do because few seem to pull it off. A good trigger is not the lynchpin that holds good shooting together, but it definitely makes it easier.

Holster Support

Guns that are meant to be carried should be carried in holsters. A gun without holster support is not nearly as useful as a gun with it. There are many pocket holsters out there on the market, but as with most things, they are not all good. In fact, there are probably fewer good ones than bad ones. Before buying a new handgun, I always check to see if holsters are available first.

Parts Support

Everything breaks eventually. Guns are no different. Full-size guns require periodic maintenance. Even more so their smaller counterparts. There are many things that can go wrong on a handgun, especially if it is a small one. Having access to the parts to make it right again, instead of having to send it off to the manufacturer and wait for it to come back, is a worthwhile thing to need a gun

Every handgun also requires periodic maintenance. In larger guns, those intervals are into the thousands of rounds before a gun needs a new spring to as reliable as possible. In pocket-sized guns, those intervals can get really small. As few as 500-1000 rounds in some cases. It is critical that end-users be able to acquire those parts to maintain the highest level of reliability possible.

There you have it. Five things to look for in that new micro-sized handgun. What else do you guys look for in guns that are this size? Hit is in the comments to let us know what we missed

Turbiaux Le Protector Palm Pistol

Photo Courtesy Cody Firearms Museum

Over the past few years, smaller and more concealable guns have hit the market — even a gun that simulates the size, shape, and appearance of a smartphone. Whether that’s a good idea or not isn’t for this historian to judge … yet. The idea of concealment in all shapes and sizes isn’t new. Back in the 1800s, many curios items came onto the market, including firearms like the Palm Protector Pistol.

This pistol is a revolver with a small barrel that fits between your fingers, kind of like parents tell their kids to do with their car keys. Instead of the cartridges being arranged in parallel around the cylinder’s axis, they were placed like spokes in a wagon wheel, much like earlier vertical turret revolvers. To fire, a shooter simply squeezes the gun. The design was first patented and sold in France in the early 1880s as the Turbiaux le Protector, but it soon saw production in the United States. Marketed by the Minneapolis Firearms Company as the Protector, it was manufactured in Springfield, Massachusetts. We don’t know of any FBI ballistic gelatin tests, but 32 Extra Short was a centerfire cartridge that made Volcanic Repeating Arms Company’s Rocket Ball ammunition look, well, still not great. Although, before we get too judgmental about the cartridge’s energy, Smith & Wesson got going thanks to sales of its number-one revolver that was chambered in the black powder 22 Short cartridge.

Peter Finnegan, who licensed the design, closed the Minneapolis Firearms Company and created the Chicago Fire Arms Company to sell a slightly different version of the guns. The manufacturing this time was done by the Ames Sword Company. Finnegan intended to have 15,000 ready by the Chicago World’s Fair, but Ames didn’t meet the deadline and a lawsuit ensued. The guns sold into the early 1900s.

Original French guns were 10-shot .22-caliber pieces, while most of the later American ones were .32 caliber, although some .41-caliber examples are reported. Originally, the guns were considered curio and relics but have since moved into the antique category under U.S. law.

Selecting a Personal-Defense Handgun: Size and Fit.

Selecting a personal-defense handgun is a very subjective endeavor. We may see a certain write-up in one of the gun magazines and think that that is just the gun for us. So we go plunk down our hard-earned cash only to find out that the gun is far from ideal. This is not necessarily the fault of a particular gun so much as it is a case of a gun that just doesn’t suit us.

As a young shooter, I was really impressed with the writings of Elmer Keith. And I quickly decided that a double-action .44 Mag. was just about the only handgun that a fellow would ever need. When I finally got the cash and took home that big DA .44, you can imagine my disappointment when I discovered that I just didn’t shoot it very well at all. The distance between the face of the trigger and the backstrap was just too long to fit my hand size. I tried all different kinds and sizes of grips, but that didn’t help. Because I couldn’t hold the revolver properly, that .44 Mag. cartridge just really beat my hand up. I know that was the case because I continue to enjoy the .44 Mag. cartridge, but in a single-action revolver, which fits my hand much better.

In order to shoot the handgun quickly and accurately, it must fit the shooter’s hand. When it does, the shooting grip feels comfortable and natural. It is this good fit that translates into quick, accurate shooting.

When a defensive shooter sets out to purchase a new handgun, this business of proper fit should be uppermost in mind. If one is not knowledgeable about handguns, it’s a good idea to take someone along who has plenty of experience so they can make sure that only quality guns are being considered. While one might have their heart set on the latest double-stacked auto, they may find that the single-stack version fits better. That experienced helper can also advise when a gun’s fit might be improved by changing to a different size of stock.

When considering a defensive revolver, there are a number of different sized stocks that can change the fit of the gun. If a 1911 might be the choice, there are long triggers and short triggers, thick stocks and thin stocks, all of which make a difference. In striker-fired pistols, the prominent companies have been good about making essentially the same gun in a double-stack version or single-stack. Many have different grip panels or backstraps to better fit the pistol to the individual’s hand.

We are blessed to live in a time when so many good defensive handguns are available for us to choose from. When making your selection, it is a good idea to choose from the best quality guns that you can possibly afford. And, among those guns, be sure to choose the one that fits your hand the best. You will find that you feel more secure with it because your grip feels comfortable and natural, more importantly, you can shoot it quickly and accurately.

Special Operations Community Embraces ‘Wildcat’ Calibers

One phenomenon that has emerged from the U.S. special operations community over the last 10 to 12 years involves exploration and acquisition of small arms in new ballistic calibers.

Rather than the better known weapon designs in 5.56 mm, 7.62 mm, .50 caliber, and even the U.S. Army’s emerging 6.8 mm Next Generation Squad Weapon, the community has embraced calibers like the .300 AAC (Advanced Armament Corporation) Blackout (.300 BLK), 6.5 Creedmoor, .300 PRC (Precision Rifle Cartridge), and both .300 and .338 Norma Magnum.

Often created as so-called “wildcat” rounds, prior to their broader acceptance and expanded production availability, these new caliber cartridges each provide a staggering array of design and performance specifics, experts said.

Recent requests for information released by U.S. Special Operations Command have identified specific command interest in a compact personal defense weapon chambered in .300 BLK.

“We’re dealing in whole different types of mission sets,” explained C.J. Dugan, vice president of business development at Maxim Defense, which has developed its own personal defense weapon designs. “The old way was, if you were doing ‘low vis’ close target reconnaissance or protection, you really only had an MP5 [9×19 mm Parabellum], which is hard to deal with these days because of parts. The only other answers you had were a pistol or a Mk18 [M4A1 (5.56×45 mm NATO) with a Close Quarters Battle Receiver variant with 10.3-inch barrel]. So trying to deal with a weapon system that would give you the right combination of distance and accuracy, and then trying to maneuver in a civilian vehicle with either only a pistol or ‘a 10.3,’ which you then had to keep out of sight, and then deal with and try to react to something, you kind of had limited expectations.”

Crediting the early development work done by Advanced Armament Corp., Dugan offered a general description of the .300 BLK design, which included “taking a 5.56 [mm] case and necking it out to a .30 cal projectile, but utilizing pistol powder inside of that, which gives you a lot of muzzle velocities that you were losing in a short barrel with a rifle round.

“In my opinion, that was the genesis of why the 300 Blackout became popular in the SOF community,” he said. “Because now, with the 300 Blackout — a .30 cal projectile loaded in a 5.56 case and burning pistol powder — you’re now getting 2,000 feet per second out of a five-and-a-half-inch gun.”

“Take a PDW for what it is — a personal defense weapon,” he summarized. “If you are pulling that thing out, things have gone really bad. … And if I am going to make a decision to engage a threat, I want to make sure that I have the best possibility for the terminal ballistics to eliminate that threat. So I combined all of that and we sat down and worked through a product deal with Fort Scott [Munitions], and I took their projectile and we put a bunch of it through our weapons and optimized different calibers for our weapons, both in the five-and-a-half-[inch barrel] and eight-and-a-half variants.”

In addition to its own PDW designs, Maxim Defense has also introduced an ammunition line and is one of more than two dozen U.S. manufacturers that currently produce a .300 BLK option.

Dugan noted that the Maxim .300 BLK is based in part on the “tumble upon impact” designs of Fort Scott Munitions, which continue to “tumble” at ballistic speeds down to 500 feet per second.

Many of Dugan’s observations were echoed by Lanse Padgett, chief executive officer of PCP Tactical LLC and Gorilla Ammunition Co.

“Gorilla Ammunition was established in 2013, and basically was founded on .300 Blackout,” he said. “We started making .300 Blackout right out of the gate, when it was just coming on the scene.”

The company has recently worked with Northrop Grumman, current operators of the government-owned Lake City Army Ammunition Plant, to manufacture “some Blackout loads for military testing.”

Describing the .300 BLK as “a phenomenal cartridge for engagements inside of 200 yards,” Padgett offered, “It is excellent for [close quarters battle]- type operations — room clearing/house clearing/building/clearing — where you can take a short barrel rifle and have almost the same ballistics as a long barrel rifle. But it makes it so much more maneuverable. And you have a much bigger projectile going at the intended target.

“For instance, the 5.56 round was designed for an M16 that had a 20-inch barrel. But now everyone wants to shoot it out of a 10-inch barrel or an eight-inch barrel and you have lost so much velocity by shaving all those inches off your barrels. So you’re now shooting a projectile that was designed to be shot at a certain velocity at much, much less velocity and you don’t have the same terminal effects that you had. … But with .300 Blackout, you’re able to shoot shorter barrels with more lethality. That’s really where I think you gain the advantage.”

Recent SOCOM requests for proposals have also identified interest in weapon designs chambered in 6.5 Creedmoor, with one recent announcement identifying a desire for a lightweight assault machine gun in 6.5 Creedmoor as a possible replacement to the current MK48 assault machine gun chambered in 7.62×51 mm NATO.

Introduced by Hornady Manufacturing Co. around 2007, Padgett said that 6.5 Creedmoor is one of five calibers of polymer cased ammunition currently manufactured by PCP Tactical, along with .50 caliber, .338 Norma Magnum, 7.62×51 mm NATO, “and some work with .260 Remington for the SOF guys.”

It was best to compare the 6.5 Creedmoor to the “traditional” 7.62×51 mm NATO round, he said.

“My ballistician would say this much more eloquently, but basically to get a better ‘ballistic coefficient,’ you want a longer, skinnier projectile,” he explained.

“The 6.5 Creedmoor offers just that in a package that is the same overall length as a .308 (7.62×51 mm) cartridge case. But now you’re getting increased velocity and a better ballistic coefficient, which means you’re going to have increased engagement distance. It’s not going to drop as fast. It’s not going to be affected by wind as much as the traditional 7.62. You’re gaining engagement distance and lethality with the extra benefit that it works in existing 7.62 length chambers. So it’s basically a barrel swap to take existing guns and turn them into 6.5 Creedmoor guns.”

Few programs more clearly reflect the embrace of new calibers better than SOCOM’s acquisitions of bolt-action sniper rifles over the past 10 to 12 years.

An example can be found in its 2009 solicitation for the Precision Sniper Rifle. Planners called for a weapon that could be switched between calibers that would include 7.62×51 mm NATO, .300 Winchester Magnum (Win Mag), and .338 Lapua Magnum. By the time that the subsequent Advanced Sniper Rifle solicitation was released in May of 2018, it specified 7.62×51 mm, .300 Norma Magnum and .338 NM — not the same as .338 Lapua.

It is broadly understood that the .338 NM represents the anti-materiel solution, the .300 NM represents the anti-personnel solution, and the 7.62×51 represents a training option that could also be applied to shorter range urban settings.

In March 2019, Barrett Manufacturing announced that its Multi-Role Adaptive Design system had been selected for the Advanced Sniper Rifle, subsequently designated as the MK22 Mod 0.

The MK22 Mod 0 is one of two Barrett sniper rifles currently being provided to special operations customers. A similar weapon, identified as the “DoD” system, is also being provided to a community element chambered in a Hornady-developed caliber identified as .300 PRC.

“Around November 2016 the Department of Defense issued a procurement for a direct and immediate warfighter capability for the .300 PRC,” said Joel Miller, director of global military sales for Barrett. “It was essentially to provide operators some greater capabilities in stand-off distances and to ensure overmatch.”

Asked about ballistic comparisons between the .300 PRC and the .300 Norma Magnum included on the ASR, Miller deferred to Hornady Manufacturing, which developed the .300 PRC.

According to Neal Emery, senior communications manager for Hornady, all of the other “big 30s” have some type of inherent design issues and the development of the .300 PRC reflected an attempt “to have something that will easily handle the long, heavy, high performance style, .30 caliber bullets with the greatest consistency possible for extended long-range shooting.”

Another long-range projectile that has been embraced by SOCOM over the last few years is the .338 Norma Magnum, with the design of both the .300 NM and .338 NM credited to ballistician Jimmie Sloan in the 2006 to 2007 timeframe.

Community acceptance of the rounds not only contributed to the change in evolution in sniper rifle requirements noted above, but has also been reflected in Special Operations Command — and Marine Corps — interest in belt-fed machine gun designs in .338 NM.

In response, General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems has been exhibiting its .338 NW Lightweight Medium Machine Gun design for the last few years.

And in January, SIG Sauer announced the safety certification and delivery of a number of its own new “338 MG” systems for special operations combat evaluations.

According to Jason St. John, director of government products in SIG Sauer’s defense strategies group, both the .338 NM and .338 Lapua reflect a sniper community desire for a flatter trajectory, larger bullet, more wind-resistant long-range capability to extend the battlefield for the sniper.

“The .308 [7.62×51 mm] was limited at about 800 meters; 1,000 to 1,200 meters for .300 Win Mag; and they wanted to push it a little bit further,” he said. “That grew into an extended range capability to have standoff with your enemy from an anti-personnel perspective.”

Noting that the .338 NM design results in a 300-grain projectile traveling at 2,900 feet per second, he credited the cartridge with “a tremendous anti-materiel capability” delivered from a 20-pound package.

“The M2A1 [.50 caliber] is an 80-pound machine gun,” he asserted. “We’re looking at a system that’s 60 pounds lighter and actually combines an anti-materiel solution and anti-personnel solution in one trim package.”

He acknowledged “some challenges” in direct comparisons with a .50 cal that has different specialized projectiles, adding, “However, when you’re looking at something like steel penetration with a .338 compared to steel penetration with a .50 cal, they are comparable at 1,200-plus meters, and in some aspects the .338 is superior in mild steel penetration at comparable distances.”

As noted earlier, the representative samples cited here are not intended to serve as complete ballistic profiles. Rather they are intended to highlight the unique characteristics of special operations missions and some of the ballistic overmatch solutions available to Special Operations Forces.

Dillon Aero completes developmental testing of their 503D .50 caliber gatling gun.

Hog Hunting In The Time Of Coronavirus

In Texas, you can still hunt feral hogs despite the lockdowns. Just make sure you prepare like it’s the end of the world.

Preparing for a hog hunt is like preparing for the end of the world. You need a reliable rifle and ammunition, of course, but you also need a bunch of other stuff—a sidearm, maps, binoculars, compass, flashlight, knife, raingear, boots, food and water, two-way radios. Once you’re all geared up, you can’t help but think that if the end came, you’d be ready.

The feeling is even more intense when you go hog hunting during a global pandemic. It might not be the apocalypse, but when it comes to buying guns and ammo—or toilet paper—it might as well be.

I know, because I recently went on a hog hunt in East Texas. Hunting feral hogs might not seem like an essential activity during coronavirus lockdowns, but here in Texas it is.

Or at least it isn’t banned. In his March 31 executive order, Gov. Greg Abbott made it clear that hunting and fishing are not prohibited so long as proper measures are taken to prevent the spread of the disease.

Some friends and I had been planning a hog hunt for months, long before the pandemic upended our lives, and as the appointed weekend neared, we decided that if the governor said we could go and the ranch owner still wanted us to come, then we’d throw some face masks and hand sanitizer in our packs and go kill some hogs. Even if we didn’t get any, it would at least get us out of the house to somewhere besides the grocery store and Home Depot.

Yes, People Hunt Feral Hogs

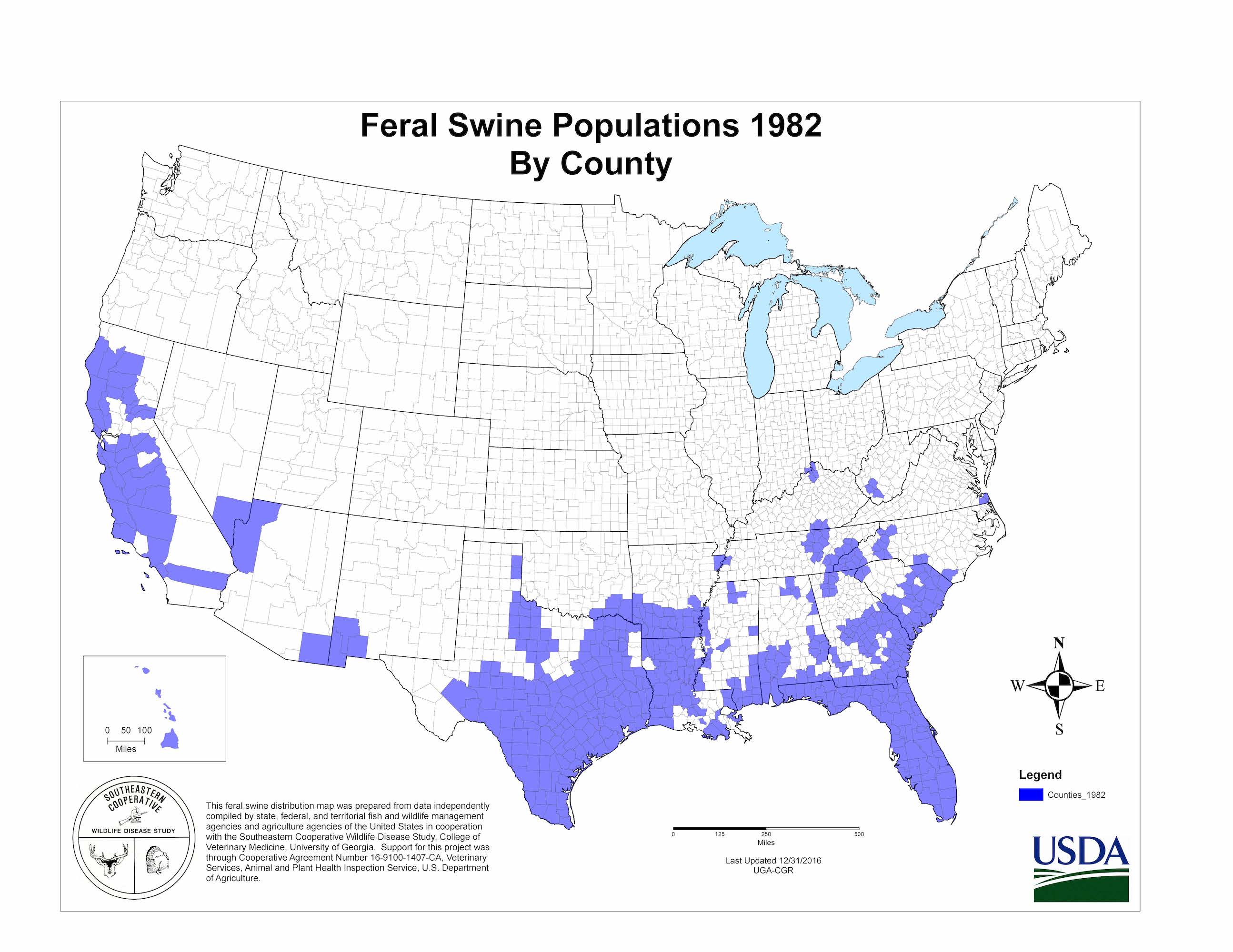

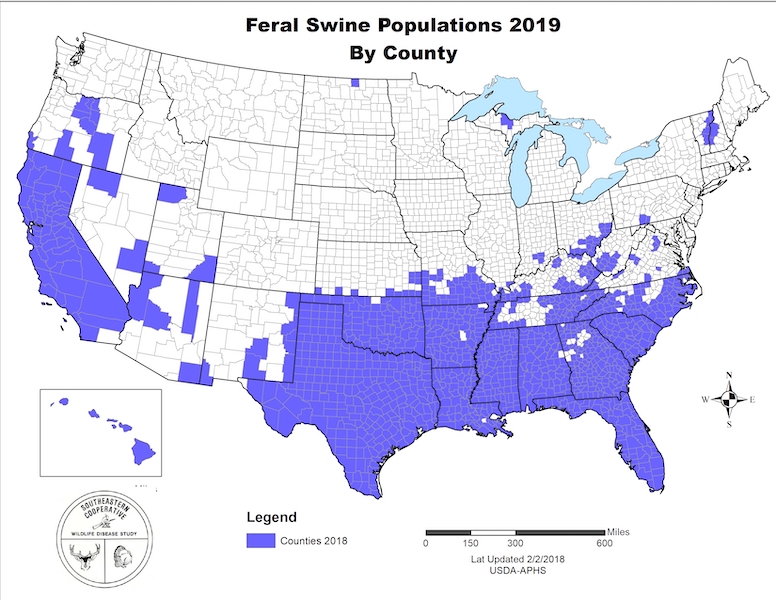

For the uninitiated, hog hunting is hugely popular across the South and especially Texas, which has the largest feral hog population in the country by far, some two million and counting (nationwide, there are between six and nine million feral hogs spread across 39 states).

Last summer, Texas lawmakers unanimously passed a law allowing anyone, resident or not, to hunt feral hogs on private land without a license, year round, with no limits. As far as the state is concerned, hunting feral hogs is pretty much like hunting rats or possums. If you see them, you can kill them.

If that seems harsh, understand that feral hogs aren’t domestic farm pigs. The term “feral hog” refers to hybrids of Eurasian wild boars (introduced to North America by Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century) and domesticated hogs that have escaped and gone feral. With the latter, they actually change physically, growing thick coats of hair and sharp tusks.

They’re an invasive, non-native wild species that’s incredibly destructive and sometimes dangerous. They tear up ranch land, destroy crops, infect livestock with diseases, eat endangered species, and on rare occasions will attack and kill people. In addition, they are incredibly intelligent and difficult to hunt or trap.

Many Americans have no awareness of this. Recall the “30-50 feral hogs” meme explosion that ensued when Willie McNabb, some random guy in southern Arkansas, responded to a tweet by musician Jason Isbell questioning the necessity of “assault weapons” in the wake of a mass shooting. “Legit question for rural Americans,” McNabb wrote, “How do I kill the 30-50 feral hogs that run into my yard within 3-5 mins while my small kids play?”

Everyone on the internet had a good laugh at McNabb’s expense until some people pointed out that actually, feral hogs are a problem in rural America, can be very dangerous, and sometimes travel in herds of 30 or more. The Washington Post even ran an explainer-type piece about the affair.

Four months later, after everyone had forgotten about it, Christine Rollins, a 59-year-old caretaker for an elderly couple in rural east Texas, was killed by a large herd of feral hogs after she got out of her car, right in front of the couple’s home.

Attacks like that are rare, but property damage from feral hogs is commonplace. All told, they cause about $2 billion in property damage nationwide every year, an amount that’s steadily growing. In Texas alone the annual damage estimate is in the hundreds of millions, so there’s a powerful incentive for landowners to kill or trap as many as they can.

In recent years, they’ve begun outsourcing that killing to hunters, and in the process have managed to monetize the hog problem. Today, Texas hog hunting is its own little industry. Ranches all over the state offer almost every conceivable hog hunting experience, from traditional blind hunting, walking and stalking, night hunts with thermal and night vision optics, and for those willing to spend a couple thousand dollars—at least—helicopter hunts, including helicopter hunts with fully automatic rifles. There are even places that will take you hog hunting with a pack of trained dogs and a knife. (The dogs attack and pin the hog, and you come in with a knife and stab it in the heart.)

But no matter how many hogs are hunted down, it doesn’t make a dent in the population. Every year, hunters in Texas kill tens of thousands of the animals, but there’s no way to kill or trap them faster than they can reproduce. Females can begin breeding as young as six months old and produce two litters every 12 to 15 months, with an average of four to eight piglets per litter, or in the case of older sows, 10 to 13 piglets.

Hence, the population explosion of feral hogs over the past four decades:

Once primarily a rural problem, feral hogs are now becoming a problem in suburban areas. The federal government has even taken notice. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Agriculture created an office devoted to the wild hog problem, the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, which produced a 250-page report last year on mitigation efforts……………

2020 CMP NATIONAL RIFLE AND PISTOL MATCHES CANCELLED

After thoughtful consideration and reflection, the Board of Directors of the Civilian Marksmanship Program announces the cancellation of the 2020 National Matches at Camp Perry.

“This decision was not arrived at lightly, but was prompted by restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. These matches date back to 1903 and have been held at Camp Perry since 1906,” said Judith Legerski, CMP Board Chairman.

“The health and safety of our competitors, participants, vendors, military support, volunteers and staff members is of the upmost importance — overriding even the historical imperative of maintaining the continuity of the Matches,” agreed Legerski, with Chief Operating Officer Mark Johnson and Programs Chief Christie Sewell.

“We were unable to come up with a manner in which we could safely produce the Matches. Housing and pit duty were amongst the many insurmountable problems faced by the CMP Board,” Legerski explained.

The CMP looks forward to the 2021 National Matches at Camp Perry as the best marksmanship celebration ever! In the meantime, please stay safe and healthy at home, as we prepare for the new normal ahead of us.

All CMP operations have been shut down since mid-March and a full resumption of business remains undetermined. Full refunds will be made to those who have already registered.

5 CCW Tips For Older Armed Citizens

By Sheriff Jim Wilson

As we get older, we must keep in mind that we can still be a target for criminal attack. In fact, we may become even more of a target as the years catch up with us. The crooks see the gray hair, the wrinkles and figure that we will be less likely to resist and less likely to be armed. Age may cause us to have physical problems to deal with, but many of them can be overcome. We owe it to ourselves and our families to be as tough a target as is humanly possible. Here are a few ideas to help older defensive shooters deal with their issues.

1. Use The Most Powerful Handgun That You Can Shoot Quickly And Accurately.

You may be surprised to learn that this is what I tell all shooters, regardless of their age. However, you may have found that, due to infirmities, you can no longer manage that .357 Mag. or .45 ACP pistol. This doesn’t mean that you should quit. It means that you should scale down to a 9 mm Luger, .38 Spl., .380 ACP, or even .22 LR, depending upon your particular needs and abilities.

These smaller calibers may not be as capable, but they sure do beat fighting with your fists…..

2. Consider Changing Carry Positions.

One of the most common defensive carry techniques is to wear the handgun on your strong-side hip, just behind the hip bone. Unfortunately, with aging, many shooters lose mobility in their joints. To make a draw from this popular position, your shoulder must move up and back, and it must do it quickly. Some folks just have a tough time with this…………

3. Dealing With Fuzzy Sights.

About the time that we hit middle age, the sights on a handgun sure do start to look fuzzy, and a clear sight picture rapidly becomes a thing of the past. Some folks deal with this natural phenomenon by using the close-range portion of their bifocals. However, for all of us, glasses are the answer.

Even if you don’t use bifocals, your optometrist can have a corner of your glasses ground so that you can see the sights clearly through that portion of the lens. …………

4. Weakness In The Hands And Forearms.

Some older shooters find that, due to arthritis or some other ailment, they can no longer work the slide on a semi-automatic pistol. In most cases, I have found that they have been doing it wrong in the first place.

Too many shooters want to hold the auto pistol in their hand with the arm almost fully extended. Then they use the thumb and index finger of their support hand, at the very back of the slide, to work the slide and chamber a round. This whole technique looks very much like the way we shot slingshots when we were kids. Regardless of age, this is a very poor technique and is an indication of someone who is a real tenderfoot regarding this business of self-defense.

The closer your hands are to your chest, the more strength you have in your hands and arms. Hold the pistol close to your chest and parallel to your chest, with the muzzle pointed to the side. However, you should be conscious that the muzzle is still pointed in a safe direction at all times.

Put your support hand over the top of the pistol, in the area of the ejection port, and grasp the slide firmly with your whole hand and all of your fingers. At the same time that you pull the slide to the rear with your support hand, you should push forward with your strong hand. The isometric push-pull, along with holding the gun close to the body, utilizes much more of your bodily strength and is a much more positive way to charge your auto pistol.

However, there are those who simply are dealing with issues that make them too weak to run an auto slide. They might consider making the transition to a double-action revolver.

5. Increase Mobility With Exercise.

The older we get, the more important exercise is to our maintaining our body strength and mobility. If you have health issues, it is critical that you do not start an exercise program without consulting with a physician. Just as with the optometrist, you may find it a bit more comfortable to find a physician who enjoys the shooting sports.

When you start hunting for a doctor who is a member of our shooting fraternity, you will be amazed at just how many of them there are. I don’t want to sound “New Age” here, but the fact is that a yoga class, especially one for older folks, is a great way to increase your agility and mobility. However, if you have any doubts about your ability, take the time to consult with a physician.

In August 2013, DEFCAD released the public alpha of its 3D search engine, which indexes public object repositories and allows users to add their own objects. The site soon closed down due to pressure from the United States State Department, under the pretense that distributing certain files online might violate US Arms Export ITAR regulations.

From 2013 to 2018, DEFCAD remained offline, pending resolution to the legal case Defense Distributed brought against the State Department, namely that ITAR regulations placed a prior restraint on Defense Distributed’s free speech, particularly since the speech in question regarded another constitutionally protected right: firearms. While the legal argument failed to gain support in federal court, in a surprise reversal in 2018, the State Department agreed that ITAR did in fact violate Defense Distributed’s free speech. Therefore, for a brief period in late 2018 DEFCAD was once again publicly available online.

Shortly thereafter, 20 states and Washington DC sued the State Department, in order to prevent DEFCAD from remaining online. At its core, this new suit (correctly) cited a procedural error: the proper notice had not been given prior to enacting the change in how ITAR applied to small arms. As such, DEFCAD was once again taken offline, pending the State Department providing proper notice via the Federal Register.

On March 28, 2020, DEFCAD once again became publicly available online

Gun-Rights Activist Releases Blueprints for Digital Guns

Cody Wilson calls the move impervious to legal challenge