The audio recording 👇 h/t @KarluskaPpic.twitter.com/TwNlR0h2Nq

— E 🇺🇸 (@Simply4Truth_) June 3, 2024

Category: Scratch a Lib-Find a Tyrant

Breyer’s ‘Pragmatic’ Approach to Destroying the Second Amendment

Former Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer may no longer be in a position to decide cases that come before the Court, but he’s still trying to shape the judiciary in a way that would allow for judges to uphold virtually every gun control law the anti’s could dream up.

Breyer’s new book Reading the Constitution; Why I Chose Pragmatism, Not Textualism outlines his approach to interpreting the Constitution. I’m actually surprised he managed to fill several hundred pages with material, given that his view is basically that judges should have the power to ignore what the text of the Constitution has to say if they don’t like it.

Breyer highlights the need for considering the broader context in which laws are passed and the “practical consequences” of different interpretations. He refers to the majority judgment in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022), in which he dissented. The Court held, 6–3, that New York’s law requiring a citizen to have a license to carry a gun outside his home violated the right to carry arms under the Second Amendment to the Constitution. Breyer expresses his disagreement with the ruling by emphasizing his preference to prioritize the practical implications. Considering the alarming patterns of gun violence in the US, Breyer believes the Court should have limited the access to firearms.

Does Breyer not know his history, or is he just choosing to ignore it? The Second Amendment was ratified shortly after a civil war that not only brought the United States its independence but led to small-scale reprisals between patriots and loyalists throughout the course of the war. As the Bill of Rights was being drafted and debated, the memory of Shay’s Rebellion was fresh in the mind of the Framers, while the Whiskey Rebellion broke out along the western frontier the same year the Second Amendment was ratified. The Founders knew all about “gun violence”. They just didn’t believe that disarming the American people was the answer.

Breyer’s criticism of textualism is based on his adherence to pragmatism. He contends that judges should endeavour to interpret the Constitution in a manner that is pragmatic and adaptable to the requirements of modern society. According to him, this approach is better aligned with the intentions of the Constitution’s framers, who intended for the constitution to be “workable” and responsive to evolving circumstances.

The Constitution is responsive to “evolving circumstances”, but the proper way to do that is through an amendment, not a panel of nine justices deciding that is language can be discarded because they think it’s right thing to do in our modern age.

Breyer’s not the first to adopt a “pragmatic” approach to the Constitution, of course. I’d argue that Roger Taney’s decision in Dred Scott is actually a pretty good example of the pragmatic philosophy that Breyer espouses. Taney twisted the Constitution’s text beyond recognition in order to reach his conclusion that black Americans could never be entitled to citizenship and that Congress had no power to regulate slavery in the territories. He did so in the belief that the practical implications of his ruling would make the country a more peaceful place by removing the issue of slavery and abolition (which Taney considered an act of “Northern aggression” from the national debate.

Pragmatism, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. In Bruen, Breyer (joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan) argued that the majority opinion “refuses to consider the government interests that justify a challenged gun regulation, regardless of how compelling those interests may be,” adding “the Constitution contains no such limitation, and neither do our precedents.”

The text of the Second Amendment doesn’t include a clause after “shall not be infringed” that says “unless the government thinks there’s a good reason to do so”. The entire purpose of the Bill of Rights is to restrain the government from violating our individual rights, and the Fourteenth Amendment applies those protections to abuses from state and local governments as well. The only pragmatic way to change that while remaining faithful to the Constitution is to pass another amendment negating the right to keep and bear arms. That option has been available to the gun control lobby for decades, but as we’ve seen with Gavin Newsom’s proposed constitutional amendment, it’s not feasible because the support simply isn’t there.

Since repealing the right to keep and bear arms is off the table, Breyer (and others) are left to insist that the Constitution is essentially whatever they want it to be. That judicial arrogance is at the heart of some of the worst legal decisions in this country, including Dred Scott, but thankfully was consigned to the minority in Bruen. If Democrats are able to reshape the court in their image after the November elections, however, that “pragmatic” approach could very well become the majority view on the Court. Our right to keep and bear arms could disappear as quickly as Dred Scott’s right to live free did in 1857; not because the Constitution demands that result, but because the “pragmatic” enemies of individual liberty do.

California Violated the Second Amendment by Disarming People Based on Nullified Convictions

A federal judge ruled that three men who committed nonviolent felonies decades ago are entitled to buy, own, and possess guns.

The state of California employed Kendall Jones as a correctional officer for 29 years and as a firearms and use-of-force trainer for 19 years. But in 2018, when Jones sought to renew the certificate of eligibility required for firearms instructors, the California Department of Justice (DOJ) informed him that he was not allowed to possess guns under state law because of a 1980 Texas conviction for credit card abuse. Jones committed that third-degree felony in Houston when he was 19, and his conviction was set aside after he completed a probation sentence.

According to the DOJ, that did not matter: Because of his youthful offense, which Jones said involved a credit card he had obtained from someone who falsely claimed he was authorized to use it, the longtime peace officer was permanently barred from owning or possessing firearms in California. That application of California law violated the Second Amendment, a federal judge ruled this week in Linton v. Bonta, which also involves two other similarly situated plaintiffs.

“Plaintiffs were convicted of non-violent felonies decades ago when they were in the earliest years of adulthood,” U.S. District Judge James Donato, a Barack Obama appointee, notes in an order granting them summary judgment. “Each conviction was set aside or dismissed by the jurisdiction in which the offense occurred, and the record indicates that all three plaintiffs have been law-abiding citizens in every respect other than the youthful misconduct. Even so, California has acted to permanently deny plaintiffs the right to possess or own firearms solely on the basis of the original convictions.” After considering the state’s cursory defense of those determinations, Donato thought it was clear that California had “violated the Second Amendment rights of the individual plaintiffs.”

Like most jurisdictions, California prohibits people with felony records from buying, owning, receiving, or possessing firearms. That ban encompasses offenses that did not involve weapons or violence, and it applies regardless of how long ago the crime was committed. Federal law imposes a similar disqualification, which applies to people convicted of crimes punishable by more than a year of incarceration (or more than two years for state offenses classified as misdemeanors). But the federal law makes an exception for “any conviction which has been expunged, or set aside or for which a person has been pardoned or has had civil rights restored.”

California’s policy is different. “The DOJ will permit a person with an out-of-state conviction to acquire or possess a firearm in California only if the conviction was reduced to a misdemeanor, or the person obtained a presidential or governor’s pardon that expressly restores their right to possess firearms,” Donato explains. The requirements for California convictions are similar.

In Jones’ case, the same state that suddenly decided he was not allowed to possess guns employed him as the primary armory officer at the state prison in Solano, where he specialized in “firearms, chemical agents, batons and use of deadly force training,” for nearly two decades. Despite all that experience, the sudden denial of his gun rights put an end to his work as a law enforcement firearms and use-of-force instructor in California. The other two plaintiffs told similar stories of losing their Second Amendment rights based not only on nonviolent offenses that happened long ago but also on convictions that were judicially nullified.

According to the 2018 complaint that Chad Linton filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, he was pulled over by state police in 1987, when he was serving in the U.S. Navy at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island in Washington. The complaint concedes that Linton was “traveling at a high rate of speed” on his motorcycle while “intoxicated” and that he initially “accelerated,” thinking “he might be able to outrun” the cops before he “reconsidered that idea, pulled over to the side of the highway, and voluntarily allowed the state trooper to catch up to him.”

Linton was charged with driving under the influence, a misdemeanor, and attempting to evade a police vehicle, a Class C felony. He pleaded guilty to both charges and received a seven-day sentence, time he had already served. In 1988, he “received a certificate of discharge, showing that he successfully completed his probation.” It “included a statement that ‘the defendant’s civil rights lost by operation of law upon conviction [are] HEREBY RESTORED.'”

Linton, who was born and raised in California, returned there in 1988 after he was discharged from the Navy. He successfully purchased several firearms after passing background checks. But when he tried to buy a handgun in 2015, the DOJ told him he was disqualified because of the 1987 felony conviction. In response, he asked the Superior Court of Washington to vacate that conviction, which it did in April 2016. The order “set aside” the conviction and released Linton “from all penalties and disabilities resulting from the offense.” But when he tried to buy a rifle in November 2016, he was rejected.

The same thing happened in March 2018, when Linton tried to buy a revolver for home protection. The following month, Donato notes, “DOJ agents came to Linton’s home and seized several firearms from him that he had legally acquired and owned for years, including an ‘antique, family-heirloom shotgun.'”

Although Linton moved to Nevada in 2020, partly because of these experiences, he still owns a cabin in California. He said he felt “unsafe and unprotected” there “without at least the option of having appropriate firearms available or at hand if needed.” He added that he “would like to be able to possess or handle firearms or ammunition for recreational purposes, such as target shooting,” while visiting friends and relatives in California.

Paul McKinley Stewart’s disqualifying offense dates back even further than Jones’ and Linton’s. In 1976, when he was 18 and living in Arizona, he “stole some tools from an unlocked truck in a commercial yard.” He was found guilty of first-degree burglary, a felony, and served three years of probation, after which he was told that his conviction had been dismissed.

Stewart moved to California in 1988 and tried to buy firearms in 2014 or 2015 (the record is unclear on the exact date). The DOJ “advised him that he was ‘disqualified’ from purchasing or possessing firearms ‘due to the presence of a prior felony conviction.'” Like Linton, Stewart went back to the court of conviction. In August 2016, Donato notes, the Arizona Superior Court “ordered ‘that the civil rights lost at the time of sentencing are now restored,’ ‘set aside [the] judgment of guilt,’ ordered the ‘dismissal of the Information/Indictment,’ and expressly held that the restored rights ‘shall include the right to possess weapons.'” The DOJ nevertheless blocked a gun purchase that Stewart attempted in February 2018, citing the 1976 conviction that officially no longer existed.

Defending these denials in federal court, the state argued that the plaintiffs were not part of “the people” whose “right to keep and bear arms” is guaranteed by the Second Amendment because they were not “law-abiding, responsible citizens.” In California’s view, Donato writes, “a single felony conviction permanently disqualifies an individual from being a ‘law-abiding, responsible citizen’ within the ambit of the Second Amendment.” He sees “two flaws” that “vitiate this contention.”

First, Donato says, “undisputed facts” establish that all three plaintiffs are “fairly described as law-abiding citizens.” Judging from the fact that “California entrusted Jones with the authority of a sworn peace officer, and with the special role of training other officers in the use of force,” that was the state’s view of him until 2018, when he was peremptorily excluded from “the people.” And as with Jones, there is no indication that the other two plaintiffs have been anything other than “law-abiding” since their youthful offenses. “Linton is a veteran of the United States Navy with a clean criminal record for the past 37 years,” Donato notes. “Stewart has had a clean criminal record for the past 48 years.”

Second, Donato says, California failed to identify any “case law supporting its position.” In the landmark Second Amendment case District of Columbia v. Heller, he notes, the Supreme Court “determined that ‘the people,’ as used throughout the Constitution, ‘unambiguously refers to all members of the political community, not an unspecified subset.'” That holding, he says, creates a “strong presumption” that California failed to rebut.

Donato notes that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit rejected California’s argument in no uncertain terms last year, when it restored the Second Amendment rights of Bryan Range, a Pennsylvania man who had been convicted of misdemeanor food stamp fraud. “Heller and its progeny lead us to conclude that Bryan Range remains among ‘the people’ despite his 1995 false statement conviction,” the 3rd Circuit said. “The Supreme Court’s references to ‘law-abiding, responsible citizens’ do not mean that every American who gets a traffic ticket is no longer among ‘the people’ protected by the Second Amendment.”

Since Jones, Linton, and Stewart are part of “the people,” California had the burden of showing that disarming them was “consistent with this Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation”—the test that the Supreme Court established in the 2022 case New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen. “California did not come close to meeting its burden,” Donato writes. It did little more than assert that Americans have Second Amendment rights only if they are “virtuous,” a criterion that is highly contested and in any case would seem to be satisfied by the plaintiffs’ long histories as productive and law-abiding citizens.

“California otherwise presented nothing in the way of historical evidence in support of the conduct challenged here,” Donato says. “It did not identify even one ‘representative analogue’ that could be said to come close to speaking to firearms regulations for individuals in circumstances akin to plaintiffs’. That will not do under Bruen.”

Donato rejected “California’s suggestion that it might have tried harder if the Court had asked.” Under Bruen, “the government bears the burden of proving the element of a national historical tradition,” he writes. “California had every opportunity to present any historical evidence it believed would carry its burden. It chose not to do so.”

Donato was dismayed by the state’s attitude. “The Court is not a helicopter parent,” he writes. “It is manifestly not the Court’s job to poke and prod litigants to live up to their burdens of proof.”

The policy that Jones, Linton, and Stewart challenged seems inconsistent with California’s criminal justice reforms, such as marijuana legalization and the reclassification of many felonies as misdemeanors. It is also inconsistent with the way California treats voting rights, which are automatically restored upon sentence completion. Gun rights in California, by contrast, are easy to lose and hard to recover, even when they have been restored by courts in other states. That disparity seems to reflect the California political establishment’s reflexive hostility to the Second Amendment.

“This case exposes the hypocrisy of California’s treatment of those convicted of non-violent crimes,” says Cody J. Wisniewski, an attorney with the Firearms Policy Coalition, one of several gun rights groups that joined the lawsuit. “While California claims to be tolerant of those that have made mistakes in the past, that tolerance ends when it comes to those individuals [who want] to exercise their right to keep and bear arms. Now, the state has no choice but to recognize the rights of peaceable people.”

And then it’ll be who’d be allowed to exercise the rights protected by the other articles in the Bill of Rights…..

Figliuzzi: More Caution Needed on Who’s Allowed to Exercise 2nd Amendment

MSNBC contributor Frank Figliuzzi commented on the shooting at the Kansas City Chiefs parade, noting similar recent incidents of gun violence disrupting places of worship and celebrations.

While the perpetrators may have legally possessed the guns used, he argued this is insufficient and society should more carefully assess who is allowed to exercise gun ownership rights.

“It’s early, but it’s never too early to talk about the role of weapons in our society. We just last weekend were reporting on a shooting at a megachurch in Houston, people going to their place of worship and that being interrupted by gunfire and a fatality. Here we are with a joyous occasion in Kansas City, and the same thing happens,” Figliuzzi said.

Figliuzzi said the media often washes its hands of these issues if the guns were legally possessed, without further examining if those individuals should have actually had access to firearms given what is known about them.

“Too often I think what the media finds is eventually a finding that perhaps that, ‘Oh, well, the perpetrators had lawful possession of those guns. Okay.’ And then they kind of wash their hands of it without a further analysis,” he said.

“Does that mean it’s okay? Does that mean that those people should have had those guns even though they might have possessed them lawfully? What do we know about them that would have caused us to do this better in terms of assessing and vetting people for gun ownership? What can we change?” he pressed.

He stressed constitutional rights should not be taken away, but that American society needs to more carefully vet who it allows to bear arms, in order to better prevent these types of tragedies from occurring.

“That’s where we seem to fall down as a society. Not that we take constitutional rights away from people, but rather that we be more careful about who it is that we allow to exercise those rights in our society,” Figliuzzi said.

How Joe Biden’s Office of Gun Violence Prevention is directing the war on guns

The White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention has become a significant threat to our guns and our civil rights.

When the office was unveiled in September 2023, President Joe Biden said it would, “centralize, accelerate, and intensify our work to save more lives more quickly. That’s what it was designed to do. It will drive and coordinate a government and nationwide effort to reduce gun violence.”

The office wields tremendous power but operates in secrecy, without oversight. It has no website. Its budget has never been made public. Its staffing levels are not known. Only three actual members have ever been identified — the director and two deputy directors. All three are radical anti-gun zealots. One has a long association with former President Barack Obama.

Neither Biden nor Vice President Kamala Harris, who oversees the office — at least officially — has ever clearly articulated what the office is supposed to do, other than “reduce gun violence” and “build on historic actions taken by President Biden to end gun violence.”

Biden’s “historic actions” are well known and include calls for red flag laws; universal background checks, which would open the door to firearm registration; banning popular semi-automatic firearms and standard capacity magazines; revoking licenses of gun dealers for minor clerical errors; and pushing Congress to pass laws that would force gun owners to comply with firearm storage regulations, which would likely be followed by mandatory home inspections to insure compliance.

Using open-source and other data, the Second Amendment Foundation examined the office’s key personnel, budget and operations. The findings reveal a Star Chamber of sorts, designed to come up with ways to chip away at the Second Amendment and then push them out to the states, without any scrutiny from Congress, the courts or the public.

“For the first time in the history of the United States a president has created an office within the White House solely to find ways to circumvent and violate the Constitution,” said SAF founder and Executive Vice President Alan M. Gottlieb. “And do not forget that taxpayer dollars are supporting this abomination. We are paying the Biden-Harris administration to violate our civil rights.”

https://t.co/rh9fDpBr38 pic.twitter.com/7xdmj77v8z

— Adam Piersen (@AdamPiersen) February 19, 2024

Soon to be followed by demand for book titles owned and what religion is practiced……..

For years, California Democrats have been hostile to gun owners. California Democrats frequently attempt to erode Second Amendment rights in the state.

A bill in the Democrat-controlled California State Assembly that was introduced on February 16th, would force homeowners and renters to disclose information about firearms they own. Assembly member Mike Gipson, and State Senator Catherine Blakespear are the two leading California Democrat lawmakers pushing this legislation.

Section 2086 will be an addition to the Insurance Code pertaining to AB-3067.

The questions include information as to the number of firearms in the home, the method of storage, and how many firearms are stored in vehicles on the property. The questions include whether or not the firearms are in locked containers or not.

A bill has been filed in California that would require homeowner's and renter's insurance companies to ask how many guns people own and to report that information to the state: https://t.co/giLP0e6DKI pic.twitter.com/XsKgKtCdKX

— Firearms Policy Coalition (@gunpolicy) February 17, 2024

Financial Big Brother is Watching You

A brief note on an overlooked nightmare.

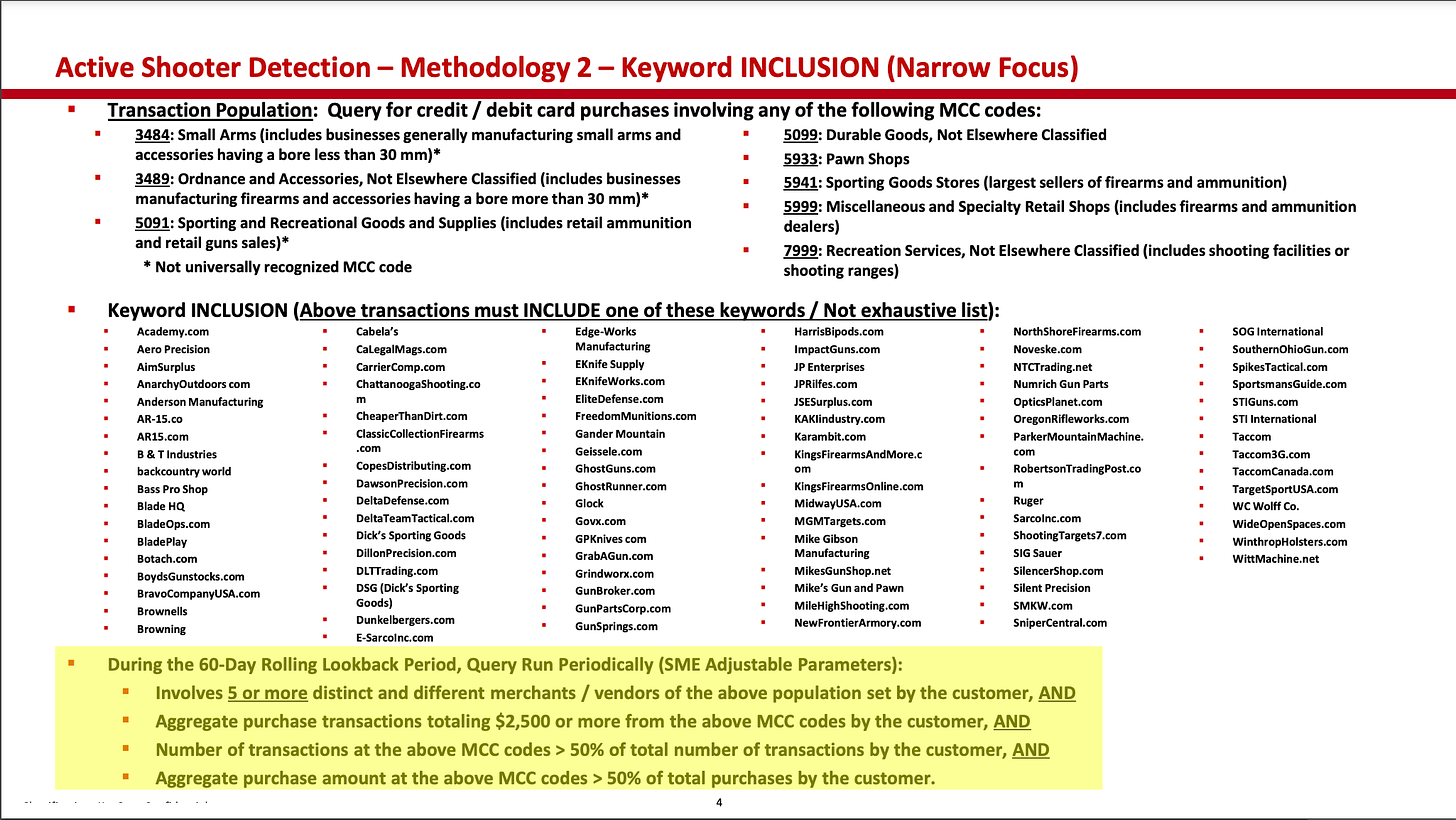

A few weeks ago, Ohio congressman and Judiciary Committee chairman Jim Jordan’s office released a letter to Noah Bishoff, the former director of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN, an arm of the Treasury Department. Jordan’s team was asking Bishoff for answers about why FinCEN had “distributed slides, prepared by a financial institution,” detailing how other private companies might use MCC transaction codes to “detect customers whose transactions may reflect ‘potential active shooters.’” The slide suggested the “financial company” was sorting for terms like “Trump” and “MAGA,” and watching for purchases of small arms and sporting goods, or purchases in places like pawn shops or Cabela’s, to identify financial threats.

Jordan’s letter to Bishoff went on:

According to this analysis, FinCEN warned financial institutions of “extremism” indicators that include “transportation charges, such as bus tickets, rental cars, or plane tickets, for travel to areas with no apparent purpose,” or “the purchase of books (including religious texts) and subscriptions to other media containing extremist views.”

During the Twitter Files, we searched for snapshots of the company’s denylist algorithms, i.e. whatever rules the platform was using to deamplify or remove users. We knew they had them, because they were alluded to often in documents (a report on the denylist is_Russian, which included Jill Stein and Julian Assange, was one example). However, we never found anything like the snapshot Jordan’s team just published:

The highlighted portion shows how algorithmic analysis works in financial surveillance. First compile a list of naughty behaviors, in the form of MCC codes for guns, sporting goods, and pawn shops. Then, create rules: $2,500 worth of transactions in the forbidden codes, or a number showing that more than 50% of the customer’s transactions are the wrong kind, might trigger a response. The Committee wasn’t able to specify what the responses were in this instance, but from previous experience covering anti-money-laundering (AML) techniques at banks like HSBC, a good guess would be generation of something like Suspcious Activity Reports, which can lead to a customer being debanked.

If Facebook, Twitter, and Google have already shown a tendency toward wide-scale monitoring of speech and the use of subtle levers to apply pressure on attitudes, financial companies can use records of transactions to penetrate individual behaviors far more deeply. Especially if enhanced by AI, a financial history can give almost any institution an immediate, unpleasantly accurate outline of anyone’s life, habits, and secrets. Worse, they can couple that picture with a powerful disciplinary lever, in the form of the threat of closed accounts or reduced access to payment services or credit. Jordan’s slide is a picture of the birth of the political credit score.

There’s more coming on this, and other articles forthcoming (readers who’ve noticed it’s been quiet around here will soon find out why). While the world falls to pieces over Tucker, Putin, and Ukraine, don’t overlook this horror movie. If banks and the Treasury are playing the same domestic spy game that Twitter and Facebook have been playing with the FBI, tales like the frozen finances of protesting Canadian truckers won’t be novelties for long. As is the case with speech, where huge populations have learned to internalize censorship rules almost overnight, we may soon have to learn the hard way that even though some behaviors aren’t illegal, they can still be punished with great effectiveness, in a Terminator-like world where computers won’t miss anything that moves.

What a crazy time we live in! See you from the Nevada caucus, and watch this space for other news soon.

"The spirit of Aloha clashes with a federally-mandated lifestyle that lets citizens walk around with deadly weapons during day-to-day activities." pic.twitter.com/DdwnHubRmK

— Firearms Policy Coalition (@gunpolicy) February 7, 2024

Of course you interview Putin: The media now opposes freedom of the press. We live in Bizarro World.

Tucker Carlson announced on Twitter that he will be interviewing Vladimir Putin. It will be posted on Twitter.

Carlson explained why: “Here’s why we’re doing it. First, because it is our job. We’re in journalism. Our duty is to inform people.”

He went on for another four minutes but in 20 words, he gave the only explanation that matters. I wish he would drop the imperial first-person.

Among the many replies, Ian Miles Cheong said, “Massive credit to Elon Musk for allowing the video to be posted uncensored. It’ll surely be banned elsewhere.”

Alex Barnicoat tweeted, “Tucker Carlson is about to save us from World War 3 with Russia. The West needs to hear the other side of the story.”

Preventing World War 3? This is why they hate him and why they hate Trump. These idiots want another world war and they really don’t care if America loses.

All evidence points to their desire to lose so they can set up a totalitarian government. The traitors in Washington have emasculated the military and literally cut the balls off generals. They opened the border to allow our enemies in. The traitors welcome Muslim terrorists and Chinese spies. The traitors depleted our military supplies by giving them away to Afghanistan and Ukraine.

You know, FDR never gave away a daggone thing. He made our allies take out loans to pay for the war materiel we sent them.

The traitors oppose giving Putin’s side of the story, as self-servingly ridiculous as it likely will be. Carlson told the Swiss magazine, Die Weltwoche, last fall that the Biden administration prevented him from interviewing Putin.

Carlson said, “I tried to interview Vladimir Putin, and the U.S. government stopped me. By the way, nobody defended me. I don’t think there was anybody in the news media who said, ‘Wait a second. I may not like this guy, but he has a right to interview anyone he wants, and we have a right to hear what Putin says.’

“You’re not allowed to hear Putin’s voice. Because why? There was no vote on it. No one asked me. I’m 54 years old. I’ve paid my taxes and followed the law.”

Nevertheless, Adam Kinzinger of CNN, a former congressman, tweeted, “He is a traitor.”

Not to be outdone, Bill Kristol said, “Perhaps we need a total and complete shutdown of Tucker Carlson re-entering the United States until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on.”

White House Wants Schools to Gaslight Parents About Guns

The White House wants to enlist school officials to help hoodwink parents about its gun control plans, according to a statement issued last week.

The reason is simple: They want to take advantage of the officials’ credibility, which the White House lacks, especially when it comes to guns.

Teachers and administrators, the White House said in the statement, “can be trusted, credible messengers when it comes to providing guidance on gun violence prevention and safe firearm storage options.”

“This issue matters to the President. It weighs on his heart every day. And he’s not going to stop fighting until we’ve solved it,” Jill Biden said last week while touting the plan at a “Gun Violence Prevention Event,” which was held in the Indian Treaty Room of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building.

From a civil rights perspective, the most worrisome portion of the White House plan is a customizable “communications template,” which school officials “can use to engage with parents and families about the importance of safe firearm storage and encourage more people to take preventive action by safely storing firearms.”

The template is designed so school officials can insert the name of the school and their letterhead to make it appear as though the document came from the school and not the White House. In fact, neither the White House nor the Biden-Harris administration are even mentioned in the document.

and

Sincerely, [INSERT NAME OF SCHOOL OR SCHOOL DISTRICT ADMINISTRATOR]

“We encourage all school leaders to consider taking steps to build awareness in your school community about safe firearm storage, such as:

- Share information about safe firearm storage with parents and families in your school communities. You can use the enclosed letter as a resource for parents, families, guardians, and caregivers—as well as teachers and school staff—to help build awareness around safe firearm storage, including what people can do to safely store firearms in their homes and spaces that children may occupy. You can also customize the letter to better meet your community’s needs.

- Partner with other municipal and community leaders to help improve understanding of safe firearm storage and broader gun violence prevention efforts.

- Engage other organizations and partners within your community, such as parent organizations, out-of-school time program leaders, nonprofit agencies, and other community-based youth-serving entities who routinely interact with children, teens, families, guardians, and caregivers, to inform them about the importance of safe firearm storage.

- Integrate information about safe firearm storage into your communications with families, guardians, and caregivers about overall emergency preparedness and school safety.”

Propaganda

There is a lot going on here, and none of it is good.

The White House’s template is classic propaganda, in which a target audience is unaware they are being influenced and unaware of the true source of the message.

It is a psychological operation, or psyop, which targets unsuspecting Americans. Before the Bidens moved into the White House, that wasn’t supposed to happen. Nowadays, it’s become commonplace.

That the White House and its gun control office would publicly propose such a plan proves they do not fear exposure from the legacy media. This, too, is telling. They know who their friends are and don’t worry about repercussions.

School officials will have little choice but to participate in this scam. Secretary Cardona’s letter will see to that.

Joe Biden, or more likely his handlers and puppeteers, have rewritten the rules to further their war on our guns. Now, anything goes, including psyops and other forms of gaslighting and deception.

The White House statement also mentions that faith leaders and law enforcement have credibility in their communities.

There’s little doubt the Biden-Harris administration will make a run at the nation’s clergy next.

Just me, but if Texas is going to buck a tyrannical DC about the border, why not about building LNG plants and drilling for more and telling DC where they can go and how to get there?

Land Commissioner Says Biden Stopped Approval of LNG Exports in Retaliation of Texas’ Defiance

The Texas Land Commissioner is accusing President Joe Biden of deliberately ending the approval of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) exports.

Dawn Buckingham believes Biden is playing political games with Texas after the state “took a bold stand in defending our border against foreign invaders.”

Stopping the approval of(LNG) exports looks “more like retaliation than a sound policy decision,” Buckingham said.

On January 26, Biden announced he was placing a “temporary pause on pending decisions of Liquified Natural Gas exports.” This was the same day the Department of Homeland Security sent a letter to the State of Texas demanding access to Shelby Park in Eagle Pass, Texas.

Buckingham called the decision “reckless,” saying that it was done in spite rather than of policy decisions.

“I will always defend Texas’ right to energy independence and stand up for the hardworking families and countless Texas schoolchildren this move will harm,” the commissioner said.

In defense, Biden claimed his decision was aligned with his policies to “tackle the climate crisis at home and abroad. While MAGA Republicans willfully deny the urgency of the climate crisis, condemning the American people to a dangerous future, my Administration will not be complacent.”

Texas is the largest exporter of natural gas in the United States and the third-largest in the world.

Bill Gates: AI Will Save ‘Democracy,’ Make ‘Humans Get Along With Each Other’ & ‘Be Less Polarized’

Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates has suggested that he hopes artificial intelligence (AI) will dictate how “humans” behave toward one another.

According to Gates, powerful AI technology will “help” society to “be less polarized.” Gates believes allowing the human race to have different opinions regarding politics and society is a “super-bad thing” because it “breaks democracy.”

In a Thursday podcast discussion with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, Gates said that AI can fix these alleged problems by making “humans” “get along with each other.”

Gates also expressed his vision of how AI could lead to increased world peace and social cohesion in an ideal world in the episode of “Unconfuse Me with Bill Gates” posted to GatesNotes, the billionaire’s blog website.

On Thursday, Microsoft briefly usurped Apple to become the world’s biggest company by market value. The company’s soaring value is due to the boom in artificial intelligence, which has given a massive boost to Microsoft.

The software company’s shares climbed around 1 percent in early trading on Thursday to take its market value to $2.87tn, just ahead of the iPhone maker, whose shares fell by almost 1 percent.

Both Microsoft and OpenAI, along with their main figureheads, have been involved in AI regulatory talks with the White House, senators, and world leaders. “I do think AI, in the best case, can help us with some hard problems,” Gates stated. “Including polarization because potentially that breaks democracy and that would be a super-bad thing.”

During the podcast, Gates and Altman also discussed the potential for AI to establish world peace.

“Whether AI can help us go to war less, be less polarized; you’d think as you drive intelligence, and not being polarized kind of is common sense, and not having war is common sense, but I do think a lot of people would be skeptical,” Gates said. “I’d love to have people working on the hardest human problems, like whether we get along with each other. I think that would be extremely positive if we thought the AI could contribute to humans getting along with each other.”

“I believe that it will surprise us on the upside there,” Altman responded. “The technology will surprise us with how much it can do. We’ve got to find out and see, but I’m very optimistic. I agree with you, what a contribution that would be.”

LISTEN:

Same energy https://t.co/QLlDO2EX7S pic.twitter.com/SVtFluReJg

— Matthew Foldi (@MatthewFoldi) January 8, 2024

It's good when the mask slips to reveal the reactionary left fascist writhing underneath.

— TANSTAAFL6817 (@tanstaafl6817) January 6, 2024

Incompetent ‘Contagious Disease’ Diagnosis for Guns a Prescription for Tyranny

“New Mexico Democratic Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham held a recent press conference to praise herself for implementing dubious gun control measures,” the National Shooting Sports Foundation reported. “‘I won’t rest until we don’t have to talk about (gun violence) as an epidemic and a public health emergency,’ the governor said.”

If a prominent politician declares an epidemic and imposes edicts and orders to enforce them, it’s fair to ask, “Where’s the science?”

“Lujan Grisham was born in Los Alamos and graduated from St. Michael’s High School in Santa Fe before earning undergraduate and law degrees from the University of New Mexico,” the governor’s official biography states. Neither her education nor her claimed career highlights show her qualified to make such a proclamation on her own, which makes it fair to ask, “Who’s advising her?”

That would be Patrick M. Allen, her New Mexico Health Department Secretary.

“In simple terms, violence, especially gun violence, behaves like a contagious disease,” Allen pontificates in his op-ed, “Tackling Gun Violence: A Public Health Challenge — DOH secretary says rapidly-spreading violence behaves like a contagious disease.”

“Imagine treating violence as if it were an infectious disease. Just as we study diseases’ origins to combat them effectively, we can apply the same approach to violence,” Allen proclaims. “How do we address gun violence as the contagious disease it is? Gun violence is a public health emergency.”

He sounds like he knows what he’s talking about, doesn’t he? The thing is, like the governor, the secretary in charge of the Land of Enchantment’s public health doesn’t have a qualified medical background, either.

Civilizational Jenga

Bit by bit, our ruling class is eliminating our societal safety margins

Politics makes me sad sometimes.

Oh, not just because politicians are doing dumb things. Not even because politicians are corrupt. Politicians have always been dumb and corrupt, as any study of history will demonstrate.

And it doesn’t matter if they hold office by election, inheritance, or swords distributed by strange women lying in ponds. Stupidity and corruption are human characteristics, and politicians are very, very human. (Though recent history is such that strange women lying in ponds distributing swords look better as the basis for a system of government . . . .)

Sometimes their stupidity and corruption make me angry, and sometimes they make me laugh. But, given my low expectations, it takes a special kind of stupidity and corruption to actually make me sad.

What makes me sad now is the ongoing game of Civilizational Jenga that our ruling class is playing. One by one, they’re withdrawing the supports of civil society, in a process that will inevitably lead to a collapse. They’re taking what was a very robust society, and consuming all the safety margins, bit by bit.

What really makes me sad is that while some of the people involved – let’s call them “the morons” for convenience’s sake – are doing this out of shortsightedness, cupidity, or sheer partisan bloodthirstiness, I’m increasingly convinced that there’s a contingent at the top that knows exactly what it’s doing, and is fine with it.

Roger Kimball gets at it in a recent piece:

“This is the same old trick,” Trump said when he got the news that the Colorado Supreme Court voted 4-3 to keep him off the primary ballot for the 2024 presidential election.

Oops. Sorry. I got my papers mixed up. That was actually Abraham Lincoln in 1860 when he got the news that some Southern states had voted to keep him off the ballot. Eventually 10 states did so.

So here we are again. It’s a bit like that Army Major in the Vietnam war who explained that they had to destroy a village in order to save it. Just so, the virtuous people of Colorado have decided that in order to save democracy they need to destroy it.

In fact, what they have just voted to preserve is not democracy but “Our Democracy™.” Here’s the difference. In a democracy, people get to vote for the candidate they prefer. In “Our Democracy™,” only approved candidates get to compete.

Donald Trump is the opposite of an approved candidate. The untrammeled hermeneutical ingenuity of the American legal profession had be let loose against Trump. As I write, he faces huge legal battle in four states. . . .

Trump is guilty not because of anything he has done but because of who he is. He is an enemy, not of the state, exactly, but of the state of mind that constitutes “Our Democracy™.” When he unexpectedly won the presidency in 2016, the beautiful people, beginning with his opponent Hillary Clinton, couldn’t believe it. They denounced the election as fraudulent. “Our Democracy™,” you see, means “rule by Democrats.”

Now they are warning that, should Trump be reelected, he would be a “dictator,” a new Hitler, etc. He would weaponise the Department of Justice against his enemies, they claim, and use the FBI to harass his opponents. Stay tuned for the seminar on what the Freudians call “projection”: it meets this afternoon in a democratic redoubt near you.

In a more civilized version of America – one that existed just a few decades ago – the notion of waging this sort of unrestricted lawfare against a leading presidential candidate, much less a former president – would have been considered ridiculous, and had it been taken seriously, would have been seen as enormously risky.

A federal judge in Illinois has declined to temporarily delay a portion of the state law banning some high-power semiautomatic weapons from going into effect.

U.S. District Judge Stephen McGlynn on Friday declined a request from several gun rights groups that would have delayed the Jan. 1 deadline for residents of Illinois to register their guns that are under the ban, according to the Chicago Tribune.

According to the report, those who have guns or accessories that are included in the ban are required to file “endorsement affidavits” with the Illinois State Police on their website.

Individuals who fail to register could be charged with a misdemeanor for the first offense and a felony for any offenses after.

McGlynn wrote in his opinion that a temporary injunction would “create further delays in this litigation when the constitutional rights of the citizens demand an expeditious resolution on the merits.”

President of Federal Firearms Licensees of Illinois, Dan Eldridge, told the outlet that the issue could end up in the Supreme Court.

“There’s a lot of stuff in motion in here,” Eldridge said.

The ban, signed by Democratic Gov. J.B. Pritzker in January, includes penalties for individuals who, “carries or possesses… manufactures, sells, delivers, imports, or purchases any assault weapon or .50 caliber rifle.”

The law also includes statutory penalties for anyone who, “sells, manufactures, delivers, imports, possesses, or purchases any assault weapon attachment or .50 caliber cartridge.”

Any kit or tools used to increase the fire rate of a semiautomatic weapon are also included in the ban, and the law includes a limit for purchases of certain magazines.

On Dec. 14, the Supreme Court allowed the law to remain in place after the National Association for Gun rights asked for a preliminary injunction.

In November, a 7th District U.S. Court of Appeals panel also refused a request to block the law. In August, the law was upheld by the Illinois Supreme Court in a 4-3 decision.

Biden Administration Urges Supreme Court To Overturn Injunction on Federal Agencies Influencing Tech Censorship

Biden wants the Supreme Court to support its censorship efforts.

The US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit recently affirmed an injunction against federal agencies to stop the current White House from colluding with Big Tech’s social media.

And now, the Biden Administration is going to the US Supreme Court in a last-ditch attempt to reverse this decision.

The big picture effect – or at least, the intended meaning – of the Fifth Circuit ruling was to stop the government from working with Big Tech in censoring online content.

There’s little surprise that this doesn’t sit well with that government, which now hopes that the federal appellate court’s decision can be overturned.

The White House says the ruling is banning its “good” work done alongside social media to combat “misinformation”; instead of admitting its actions to amount to collusion with Big Tech – which has been amply documented now, not least by the Twitter Files – the government insists its actions are serving the public, and its “ability” to discuss relevant issues.

We obtained a copy of the petition for you here.

US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy is back again here – to say that what those now in power in the US (a message amplified by legacy media) did ahead of the 2020 presidential election, as well as subsequently regarding the pandemic “misinformation” – which is now fairly widely accepted to be censorship (“moderation”) – is what Murthy still calls, justified.

By what, though? Because the appellate court’s ruling looked into the government’s “persuasive actions” (and no, you’re not reading a line from a gangster movie script, where “coercion” is spelled as, “urging”, etc.).

In any case, the appellate court found these actions were in fact coercive and unconstitutional.

Well, Murthy believes the court got it all wrong. The Fifth Circuit is accused of “improperly applying new and unprecedented” remedies. (No – he was not talking about the Covid vaccine(s). The reference was to the court’s allegedly flawed “legal theories”).

Murthy and other administration representatives are telling the Supreme Court that what the Fifth Circuit found to be unconstitutional, was actually “lawful persuasive governmental actions.”

The “grand” argument here is that, historically, US governments have been using free speech as a vehicle to promote their policies. And so – why would this case of “urging” Big Tech be any different?

“The Biden administration’s urging of social media platforms to enforce their content moderation policies to combat misinformation and disinformation is no different,” the government said.