BLUF

So there you are. A return to the rule of law, being treated as just the opposite. Par for the course in today’s political discourse, alas.

The Supreme Court, Chevron, and the Political Class’s Worst Nightmare: Accountability.

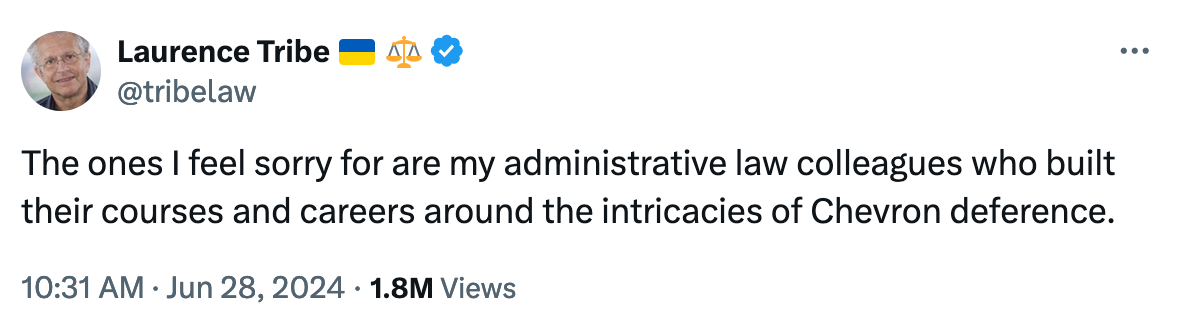

Goodbye, Chevron deference. Larry Tribe is already mourning the Supreme Court’s overturning of NRDC v. Chevron, in the Loper Bright and Relentless cases, as a national catastrophe:

Oh, the humanity!

Well, speaking as a professor of Administrative Law, I think I’ll bear up just fine. I’ve spent the last several years telling my students that Chevron was likely to be reversed soon, and I’m capable of revising my syllabus without too much trauma. It’s on a word processor, you know. As for those academics who have built their careers around the intricacies of Chevron deference, well, now they’ll be able to write about what comes next. And if they’re not up to that task, then it was a bad idea to build a career around a single Supreme Court doctrine.

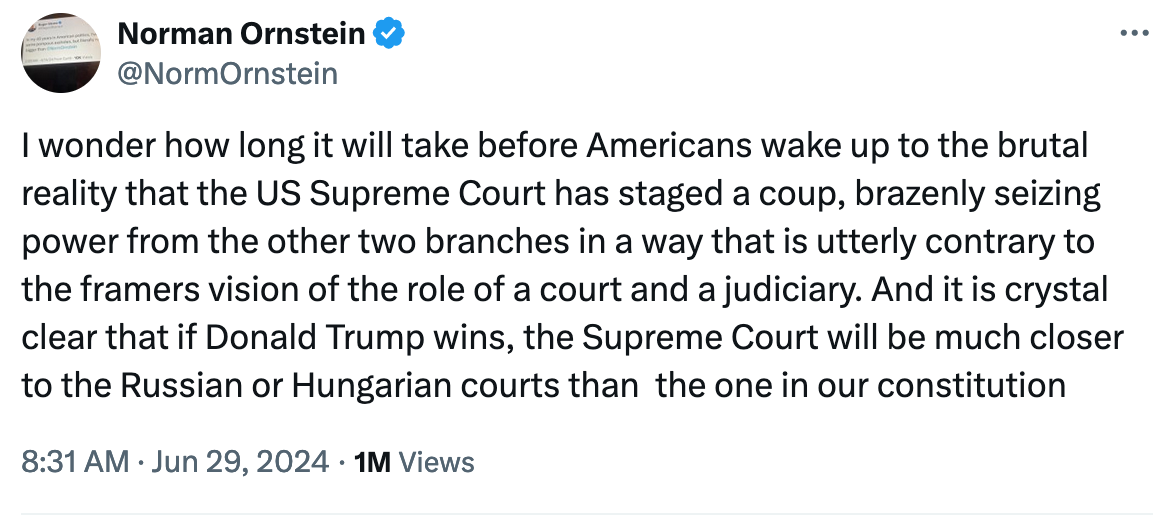

And that wasn’t the only important Supreme Court decision targeting the administrative state, a situation that has pundit Norm Ornstein, predictable voice of the ruling class’s least thoughtful and most reflexive cohort, making Larry Tribe sound calm.

Sure, Norm, whatever you say.

But how about let’s look at what the Court actually did in Chevron, and in the Loper Bright and Relentlesscases that overturned it, and in SEC v Jarkesy, where the Court held that agencies can’t replace trial by jury with their own administrative procedures, and in Garland. v. Cargill, where the Court held that agencies can’t rewrite statutes via their own regulations. I don’t think you’ll find the sort of Russian style power grab that Ornstein describes, but rather a return to constitutional government of the sort that he ought to favor.

At root, Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council is about deference. Deference is a partial abdication of decisionmaking in favor of someone else. So, for example, when we go out to dinner, I often order what my son-in-law orders, even if something else on the menu sounds appealing. I’ve learned that somehow he always seems to pick the best thing.

Deference doesn’t mean “I’ve heard your argument and I’m persuaded by it,” (though something like that is misleadingly called “Skidmore deference, “ but isn’t actually deference at all). Deference means “even if I would have decided this question differently, I’m going to go with your judgment instead.”

Under Chevron deference, when an agency interprets a statute it administers (e.g., the EPA and the Clean Air Act), a court will uphold its interpretation so long as it is (generously assessed) a reasonable one, even if it is not the interpretation the court would have come up with on its own. As you might imagine, this, at least potentially, gives agencies a lot more leeway, particularly when, as is often the case, Congress has drafted the statute ambiguously.

With Chevron overturned, courts will now apply their own judgment instead of deferring to agencies. Of course, this isn’t as big a deal as Larry and Norm seem to think, because Chevron has been dying the death of a thousand cuts for a while. Under the “major questions doctrine,” courts already decline to defer to agency interpretations where the issue has major social or economic ramifications.

So the upshot now is that if Congress wants agencies to do things, it has to tell them to. If agencies think their statutes are inadequate to their purpose, they can ask Congress to amend them. Rather than a threat to democracy, this is a modest return of decisionmaking to democratically elected legislators, and out of the hands of unelected bureaucrats.

I say modest because Chevron was dying for years, and because it was never entirely clear just how much difference it made where the rubber meets the road. Some post-Chevron studies found it made a modest difference in how often agency actions were upheld by courts post-Chevron; others held that it didn’t make much difference at all. It is, if anything, most significant as a statement of who is actually supposed to be boss in our system, and perhaps a notice that the judiciary is supposed to ride herd on agencies more closely than it has done in the past.

With that in mind, the other cases make sense too. In SEC v. Jarkesy, the Securities and Exchange Commission the Court did something similar. To quote the NCLA press release on this case (where NCLA was an amicus on the winning side):

George R. Jarkesy, Jr. was an investment professional and host of a nationally syndicated talk-radio program at the time when SEC conducted its administrative proceeding against him. He raised a constitutional claim against the SEC’s ALJs, who enjoy multiple layers of protection from removal by the President. In an earlier precedent called Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Co. Accounting Oversight Board, the Supreme Court made clear that officers of the U.S. may not be insulated from removal by multiple layers of protection without running afoul of the clause in Article II of the Constitution that requires the President to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

In addition to dismissing Mr. Jarkesy’s constitutional removal claim, SEC violated his Seventh Amendment jury-trial rights as well as the equal protection component of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The Dodd-Frank Act empowers SEC to obtain a jury trial by suing in federal court or avoid a jury trial by initiating an administrative proceeding. Enforcement targets, like Jarkesy, do not have a similar option. Thus, the law unfairly deprives them of the same right to demand a jury trial that SEC has—a blatantly discriminatory rule.

In June 2024, the Supreme Court ruled in SEC v. Jarkesy that the Seventh Amendment jury trial right applies to administrative proceedings, a historic NCLA victory.

So the SEC attempted to do administratively, via an in-house proceeding, what it is constitutionally required to do only via an Article III court with a life-tenured judge and a jury. The Supreme Court told it to follow the Constitution. Norm Ornstein thinks this is Putin-like. Spoiler: It’s not.

Then there’s Garland v. Cargill, the “bump stock” case. (This case was actually brought by the NCLA). After the still-unexplained mass shooting in Las Vegas, the BATFE rewrote its regulations to treat “bump stocks” as “machine guns.” Under the applicable statute, a machine gun is something that fires more than one round when the trigger is pulled.

Bump stocks don’t do that. Instead, they make it possible for you to essentially hold your finger steady while the gun vibrates or bounces against it, causing the trigger to be pulled more rapidly than most people can do it with a finger alone. But it’s still one trigger-pull per bullet leaving the barrel.

ATF argued, essentially, that the end result was kinda like a machine gun. The Court held that “kinda like” isn’t enough for a criminal statute. If Congress wants to make bump stocks illegal, it can (probably, subject to Second Amendment limitations) pass a law banning bump stocks. ATF, however, can’t pass laws. All it can do is adopt regulations interpreting laws, and regulations interpreting laws so that those laws do things that Congress didn’t enact aren’t “interpretations “at all, but the equivalent of new laws, which only Congress can pass. (Article I of the Constitution states plainly that “all legislative powers herein granted” belong to Congress and nobody else.)

So there we are. Rather than “brazenly seizing power from the other two branches,” the Supreme Court has returned power to Congress, where the Constitution put it to begin with. The brazen seizing, in fact, was undertaken by the unelected administrative state, what even FDR’s Commission on Administrative Government called a “headless fourth branch of government.” And that was in 1937; there’s been a lot more seizing since then.

Of course, the political class likes the administrative state for the precise reason it is constitutionally dubious – because it is not accountable to the voters. Instead, it is run by people like them, screening their often-subjective policy preferences behind confusing nomenclature, complex procedure, and (often dubious) claims of expertise. Like anything else that is a threat to the political class’s power or prestige, a return to something closer to constitutional government generates fear, hostility and – as we can see – over-the-top language. The good news is, nobody listens to the political class much anymore.

So there you are. A return to the rule of law, being treated as just the opposite. Par for the course in today’s political discourse, alas.