Hog Hunting In The Time Of Coronavirus

In Texas, you can still hunt feral hogs despite the lockdowns. Just make sure you prepare like it’s the end of the world.

Preparing for a hog hunt is like preparing for the end of the world. You need a reliable rifle and ammunition, of course, but you also need a bunch of other stuff—a sidearm, maps, binoculars, compass, flashlight, knife, raingear, boots, food and water, two-way radios. Once you’re all geared up, you can’t help but think that if the end came, you’d be ready.

The feeling is even more intense when you go hog hunting during a global pandemic. It might not be the apocalypse, but when it comes to buying guns and ammo—or toilet paper—it might as well be.

I know, because I recently went on a hog hunt in East Texas. Hunting feral hogs might not seem like an essential activity during coronavirus lockdowns, but here in Texas it is.

Or at least it isn’t banned. In his March 31 executive order, Gov. Greg Abbott made it clear that hunting and fishing are not prohibited so long as proper measures are taken to prevent the spread of the disease.

Some friends and I had been planning a hog hunt for months, long before the pandemic upended our lives, and as the appointed weekend neared, we decided that if the governor said we could go and the ranch owner still wanted us to come, then we’d throw some face masks and hand sanitizer in our packs and go kill some hogs. Even if we didn’t get any, it would at least get us out of the house to somewhere besides the grocery store and Home Depot.

Yes, People Hunt Feral Hogs

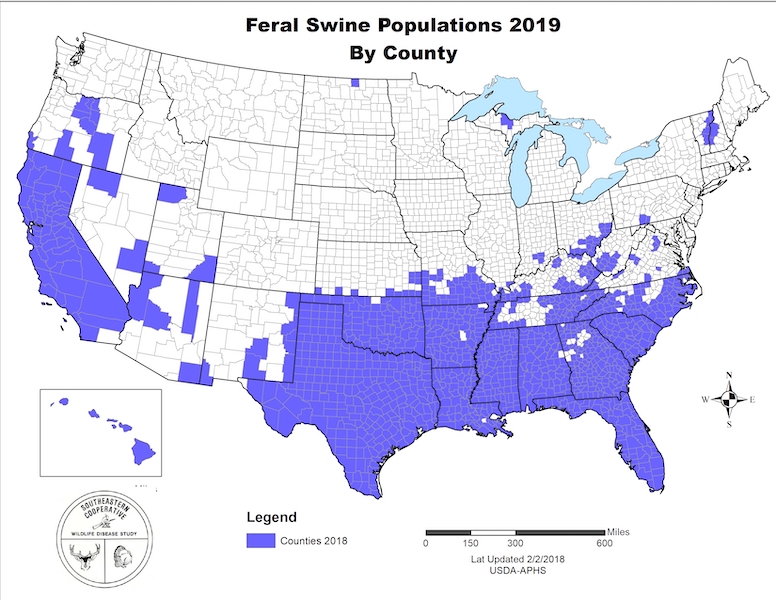

For the uninitiated, hog hunting is hugely popular across the South and especially Texas, which has the largest feral hog population in the country by far, some two million and counting (nationwide, there are between six and nine million feral hogs spread across 39 states).

Last summer, Texas lawmakers unanimously passed a law allowing anyone, resident or not, to hunt feral hogs on private land without a license, year round, with no limits. As far as the state is concerned, hunting feral hogs is pretty much like hunting rats or possums. If you see them, you can kill them.

If that seems harsh, understand that feral hogs aren’t domestic farm pigs. The term “feral hog” refers to hybrids of Eurasian wild boars (introduced to North America by Spanish conquistadors in the sixteenth century) and domesticated hogs that have escaped and gone feral. With the latter, they actually change physically, growing thick coats of hair and sharp tusks.

They’re an invasive, non-native wild species that’s incredibly destructive and sometimes dangerous. They tear up ranch land, destroy crops, infect livestock with diseases, eat endangered species, and on rare occasions will attack and kill people. In addition, they are incredibly intelligent and difficult to hunt or trap.

Many Americans have no awareness of this. Recall the “30-50 feral hogs” meme explosion that ensued when Willie McNabb, some random guy in southern Arkansas, responded to a tweet by musician Jason Isbell questioning the necessity of “assault weapons” in the wake of a mass shooting. “Legit question for rural Americans,” McNabb wrote, “How do I kill the 30-50 feral hogs that run into my yard within 3-5 mins while my small kids play?”

Everyone on the internet had a good laugh at McNabb’s expense until some people pointed out that actually, feral hogs are a problem in rural America, can be very dangerous, and sometimes travel in herds of 30 or more. The Washington Post even ran an explainer-type piece about the affair.

Four months later, after everyone had forgotten about it, Christine Rollins, a 59-year-old caretaker for an elderly couple in rural east Texas, was killed by a large herd of feral hogs after she got out of her car, right in front of the couple’s home.

Attacks like that are rare, but property damage from feral hogs is commonplace. All told, they cause about $2 billion in property damage nationwide every year, an amount that’s steadily growing. In Texas alone the annual damage estimate is in the hundreds of millions, so there’s a powerful incentive for landowners to kill or trap as many as they can.

In recent years, they’ve begun outsourcing that killing to hunters, and in the process have managed to monetize the hog problem. Today, Texas hog hunting is its own little industry. Ranches all over the state offer almost every conceivable hog hunting experience, from traditional blind hunting, walking and stalking, night hunts with thermal and night vision optics, and for those willing to spend a couple thousand dollars—at least—helicopter hunts, including helicopter hunts with fully automatic rifles. There are even places that will take you hog hunting with a pack of trained dogs and a knife. (The dogs attack and pin the hog, and you come in with a knife and stab it in the heart.)

But no matter how many hogs are hunted down, it doesn’t make a dent in the population. Every year, hunters in Texas kill tens of thousands of the animals, but there’s no way to kill or trap them faster than they can reproduce. Females can begin breeding as young as six months old and produce two litters every 12 to 15 months, with an average of four to eight piglets per litter, or in the case of older sows, 10 to 13 piglets.

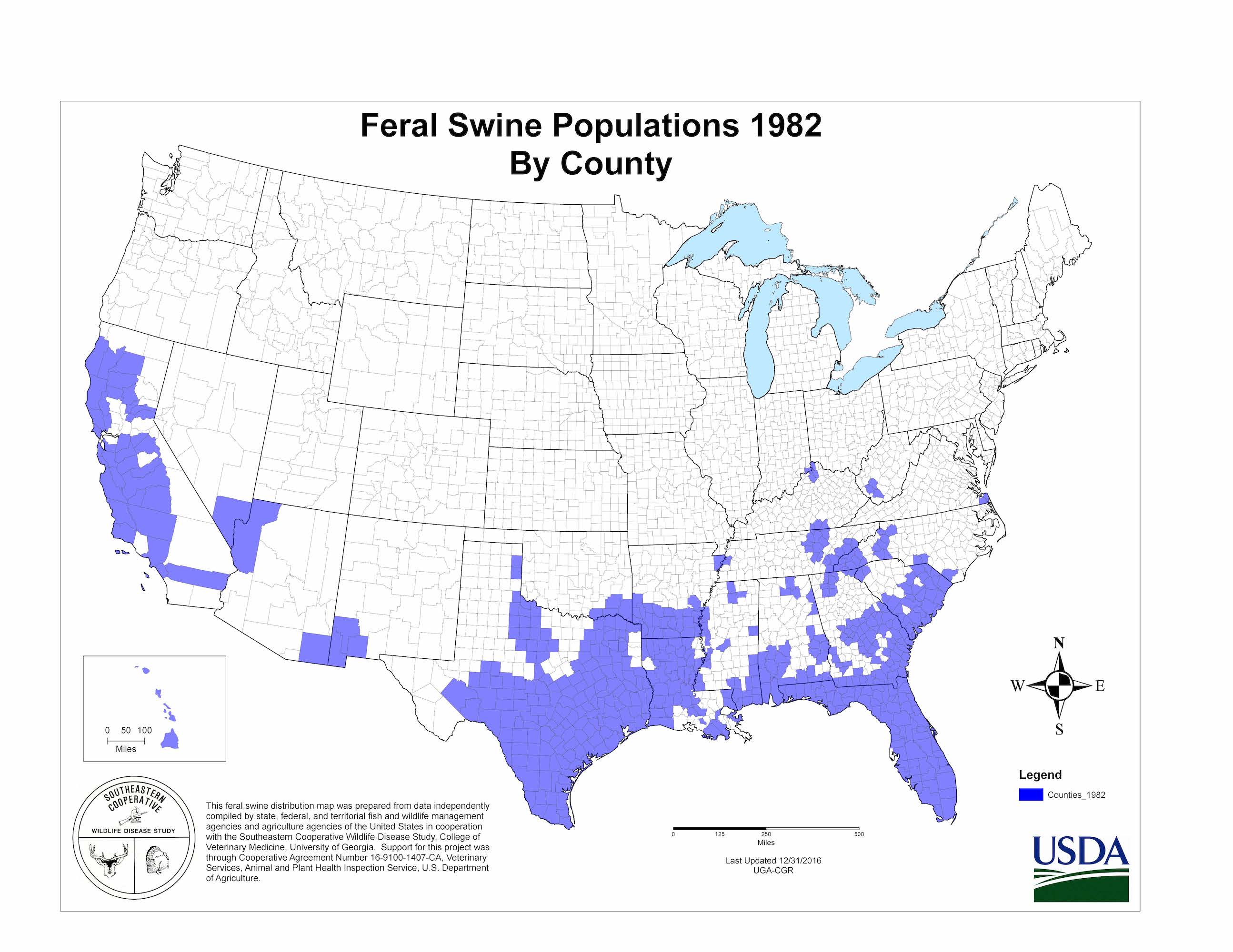

Hence, the population explosion of feral hogs over the past four decades:

Once primarily a rural problem, feral hogs are now becoming a problem in suburban areas. The federal government has even taken notice. In 2014, the U.S. Department of Agriculture created an office devoted to the wild hog problem, the National Feral Swine Damage Management Program, which produced a 250-page report last year on mitigation efforts……………