“If you don’t have it in your hands, it’s not really yours”

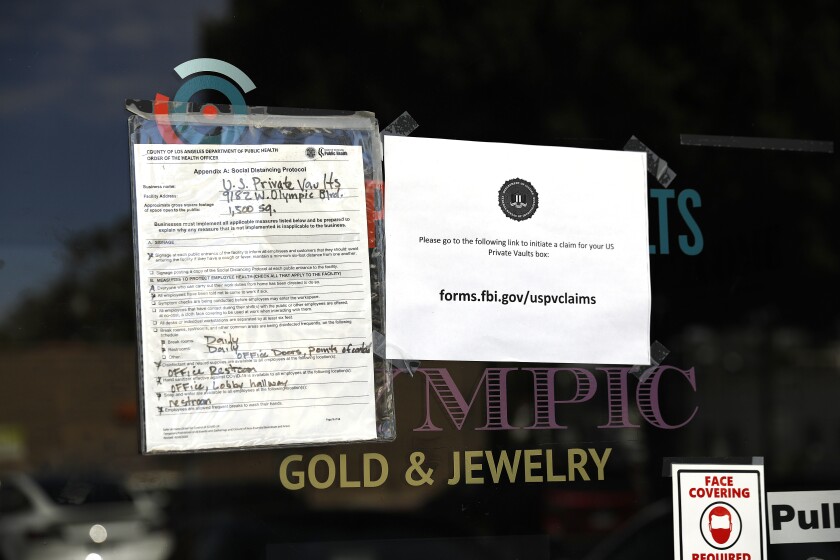

After FBI seizure of safe deposit boxes in Beverly Hills, legal challenges mount

A retired flooring contractor was watching television one night last month when he saw a news report about federal agents raiding U.S. Private Vaults, a store in a Beverly Hills strip mall that let customers rent safe deposit boxes anonymously.

He knew the place well. It’s near his home and, for years, he has rented a long, narrow box there to keep about $60,000 in cash, gold and silver. It also contained the title certificate for his pickup truck.

The 69-year-old man, who declined to be named because of privacy and safety concerns, said he has kept the stockpile of currency and precious metals since getting spooked by the 2008 financial crash. “You never know what’s going to happen, the way the world’s going today,” he said.

That financial net vanished — at least for now — in the raid.

Armed with a warrant, agents with the FBI and Drug Enforcement Administration pulled each of the store’s several hundred boxes out of the walls and seized all the contents. It took five days to inventory everything and take it to an undisclosed warehouse. Prosecutors said drugs, weapons and stacks of currency that drew the attention of drug-sniffing dogs were discovered.

To reclaim property, people must identify themselves to federal authorities and prove they are the rightful owners of the items — a bar that may prove challenging to clear when dealing with cash, gold, heirloom jewelry and other undocumented items.

The raid has set off legal challenges from five box holders who say the government violated the constitution’s ban on unreasonable search and seizure.

Klausner, however, left open the possibility that the sweeping nature of the seizures violated the box renters’ rights.

Klausner’s ruling came in the first of the five lawsuits filed by U.S. Private Vaults customers, who estimate there were 600 to 1,000 boxes in the store.

Legal scholars say the U.S. attorney’s office in Los Angeles is testing constitutional restraints on the government’s power to seize private property.

“This was at bottom executing a warrant at a business,” said Orin Kerr, a UC Berkeley law professor. “What makes it different is that hundreds of customers had their own 4th Amendment protected spaces in their safe deposit boxes. That’s what makes this unusual. It’s not just the business. It’s also users storing their things — some engaging in criminal activity, others not, I assume.”

A federal grand jury indicted U.S. Private Vaults last month on three counts of conspiracy — to distribute drugs, launder money and structure cash transactions to dodge currency reporting rules. The indictment lists four unnamed people affiliated with the business as co-conspirators but has not charged them. More charges could be filed later.

In a court statement defending the seizure, FBI agent Kathryn E. Bailey said agents searching the boxes found fentanyl, OxyContin, guns, gold bullion and stacks of $100 bills. Some of the largest-sized boxes each contained more than $1 million in cash, she said.

Customers who sued the government said prosecutors had no right to seize the contents of their boxes because they had no evidence that would give them reason to suspect the customers were stashing contraband or committing some other crime.

Jeffrey B. Isaacs, an attorney for one customer, accused prosecutors of trying to force people who want their property back to reveal their names to the FBI, subject themselves to criminal investigation and prove they lawfully acquired what they stored in the boxes.

“This is as illegal a search and seizure as I’ve ever seen,” Isaacs said. “It’s rather shocking.”

The retired Pico-Robertson contractor has not sued, but tried to file a theft report with Beverly Hills police, who refused to take it.

Klausner’s ruling rejected Doe’s request for a temporary restraining order that would have unsealed the court-approved seizure warrant; stopped inspection of any box the government has no specific justification to search; barred agents from using anything they found in such boxes in criminal investigations; and stopped the FBI from requiring personal information from people trying to retrieve their valuables.

Doe rented three boxes to store jewelry, currency and bullion, but sought a court order that applied to the whole store.

“It is possible that the government’s seizure and search of those other boxes violated the 4th Amendment rights of their owners,” Klausner wrote. But the request was “far broader than necessary” to protect Doe from harm.

The court is still considering Doe’s request for a preliminary injunction. Benjamin Gluck, his attorney, said “the government’s scheme is manifestly unconstitutional.”

In court papers filed last week, Assistant U.S. Atty. Andrew Brown said agents “seized the nests of safety deposit boxes because there was overwhelming evidence” that U.S. Private Vaults “was a criminal business.” The company’s promise of anonymity attracted criminals looking to safeguard cash, he said. Brown acknowledged some customers were “honest citizens” who should get their things back.

Standards for what makes a search legal have shifted in recent years as digital communications pose new challenges. Courts have required warrants for searches of locations where people have a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” Exceptions, however, have been made when law enforcement has sought personal data and other things that suspects have technically put in the possession of a third party like a phone company or storage facility.

In 2018, the Supreme Court narrowed those exceptions, ruling that police need a warrant to collect cellphone tracking records that can reveal everywhere a person goes. Even though the location data is kept by a private company, Chief Justice John G. Roberts wrote, “we decline to grant the state unrestricted access.”

Hadar Aviram, a UC Hastings law professor, said the warrant that remains under seal in the U.S. Private Vaults case is the key to whether prosecutors met the legal standard for breaking the box holders’ expectation of privacy. Prosecutors would need to show they had probable cause to believe evidence of criminal activity would be found in a substantial portion of the boxes — perhaps close to a third of them, she said. “There’s good cause for concern here,” she said.

Kerr, the UC Berkeley law professor, said he expected the seizure of all the boxes would ultimately hold up in court, but the legal question still did not appear “cut and dry.”

“Those property owners have their own independent rights to be secure in their persons and property,” he said. “The government can’t come in there and say, because the business allegedly did something wrong, those people are not entitled to the protections of the 4th Amendment.”