As I heard it explained many years ago; ‘Fast with a gun’ didn’t mean the “quickdraw” that western movies, TV & some artists have made famous. It meant the man was fast -as highlighted below – in deciding that he would draw and shoot and then not hesitate in doing so.

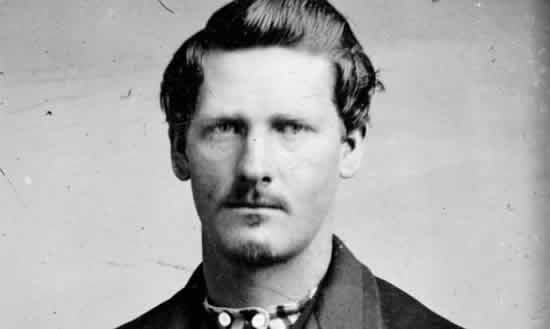

Lessons on Gunfighting from Wyatt Earp.

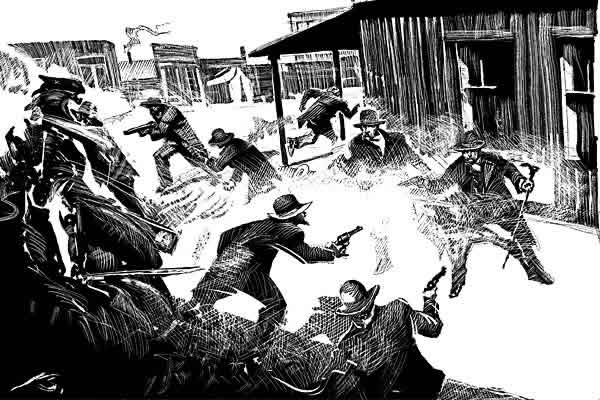

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American Old West gambler, a deputy sheriff in Pima County, and deputy town marshal in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, who took part in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which lawmen killed three outlaw cowboys.

Here is an interview that Wyatt Earp shares on “gunfighting“. This was dated back in the 1910 he offered to give an interview about his thoughts on using a gun. In his own words, Wyatt is going to explain how he became one of the most feared and accurate gunslingers… even if he was about the slowest.

The interview was originally posted on primaryandsecondary.com forum.

The most important lesson I learned from those proficient gunfighters was the winner of a gunplay usually was the man who took his time. The second was that, if I hoped to live long on the frontier, I would shun flashy trick-shooting—grandstand play—as I would poison.

I was a fair hand with pistol, rifle, or shotgun, but I learned more about gunfighting from Tom Speer’s cronies during the summer of ’71 than I had dreamed was in the book. Those old-timers took their gunplay seriously, which was natural under the conditions in which they lived. Shooting, to them, was considerably more than aiming at a mark and pulling a trigger. Models of weapons, methods of wearing them, means of getting them into action and operating them, all to the one end of combining high speed with absolute accuracy, contributed to the frontiersman’s shooting skill.

The sought-after degree of proficiency was that which could turn to most effective account the split-second between life and death. Hours upon hours of practice, and wide experience in actualities supported their arguments over style.

When I say that I learned to take my time in a gunfight, I do not wish to be misunderstood, for the time to be taken was only that split fraction of a second that means the difference between deadly accuracy with a sixgun and a miss. It is hard to make this clear to a man who has never been in a gunfight.

Perhaps I can best describe such time taking as going into action with the greatest speed of which a man’s muscles are capable, but mentally unflustered by an urge to hurry or the need for complicated nervous and muscular actions which trick-shooting involves. Mentally deliberate, but muscularly faster than thought, is what I mean. (What Wyatt meant is that he made the decision to shoot a long time before the trigger was pulled.)

In all my life as a frontier police officer, I did not know a really proficient gunfighter who had anything but contempt for the gun-fanner, or the man who literally shot from the hip. In later years I read a great deal about this type of gunplay, supposedly employed by men noted for skill with a forty-five.

From personal experience and numerous six-gun battles which I witnessed, I can only support the opinion advanced by the men who gave me my most valuable instruction in fast and accurate shooting, which was that the gun-fanner and hip-shooter stood small chance to live against a man who, as old Jack Gallagher always put it, took his time and pulled the trigger once.

Cocking and firing mechanisms on new revolvers were almost invariably altered by their purchasers in the interests of smoother, effortless handling, usually by filing the dog which controlled the hammer, some going so far as to remove triggers entirely or lash them against the guard, in which cases the guns were fired by thumbing the hammer.

This is not to be confused with fanning, in which the triggerless gun is held in one hand while the other was brushed rapidly across the hammer to cock the gun, and firing it by the weight of the hammer itself. A skillful gun-fanner could fire five shots from a forty-five so rapidly that the individual reports were indistinguishable, but what could happen to him in a gunfight was pretty close to murder.

I saw Jack Gallagher’s theory borne out so many times in deadly operation that I was never tempted to forsake the principles of gunfighting as I had them from him and his associates.

There was no man in the Kansas City group who was Wild Bill’s equal with a six-gun. Bill’s correct name, by the way, was James B. Hickok. Legend and the imaginations of certain people have exaggerated the number of men he killed in gunfights and have misrepresented the manner in which he did his killing. At that, they could not very well overdo his skill with pistols.

Hickok knew all the fancy tricks and was as good as the best at that sort of gunplay, but when he had serious business at hand, a man to get, the acid test of marksmanship, I doubt if he employed them. At least, he told me that he did not. I have seen him in action and I never saw him fan a gun, shoot from the hip, or try to fire two pistols simultaneously. Neither have I ever heard a reliable old-timer tell of any trick-shooting employed by Hickok when fast straight-shooting meant life or death.

That two-gun business is another matter that can stand some truth before the last of the old-time gunfighters has gone on. They wore two guns, most of six-gun toters did, and when the time came for action went after them with both hands. But they didn’t shoot them that way.

Primarily, two guns made the threat of something in reserve; they were useful as a display of force when a lone man stacked up against a crowd. Some men could shoot equally well with either hand, and in a gunplay might alternate their fire; others exhausted the loads from the gun on the right, or the left, as the case might be, then shifted the reserve weapon to the natural shooting hand if that was necessary and possible. Such a move—the border shift—could be made faster than the eye could follow a top-notch gun-thrower, but if the man was as good as that, the shift would seldom be required.

Whenever you see a picture of some two-gun man in action with both weapons held closely against his hips and both spitting smoke together, you can put it down that you are looking at the picture of a fool, or a fake. I remember quite a few of these so-called two-gun men who tried to operate everything at once, but like the fanners, they didn’t last long in proficient company.

In the days of which I am talking, among men whom I have in mind, when a man went after his guns, he did so with a single, serious purpose. There was no such thing as a bluff; when a gunfighter reached for his fortyfive, every faculty he owned was keyed to shooting as speedily and as accurately as possible, to making his first shot the last of the fight. He just had to think of his gun solely as something with which to kill another before he himself could be killed. The possibility of intimidating an antagonist was remote, although the ‘drop’ was thoroughly respected, and few men in the West would draw against it.

I have seen men so fast and so sure of themselves that they did go after their guns while men who intended to kill them had them covered, and what is more win out in the play. They were rare. It is safe to say, for all general purposes, that anything in gunfighting that smacked of show-off or bluff was left to braggarts who were ignorant or careless of their lives.

I might add that I never knew a man who amounted to anything to notch his gun with ‘credits,’ as they were called, for men he had killed. Outlaws, gunmen of the wild crew who killed for the sake of brag, followed this custom. I have worked with most of the noted peace officers — Hickok, Billy Tilghman, Pat Sughre, Bat Masterson, Charlie Basset, and others of like caliber — have handled their weapons many times, but never knew one of them to carry a notched gun.

There are two other points about the old-time method of using six-guns most effectively that do not seem to be generally known. One is that the gun was not cocked with the ball of the thumb. As his gun was jerked into action, the old-timer closed the whole joint of his thumb over the hammer and the gun was cocked in that fashion. The soft flesh of the thumb ball might slip if a man’s hands were moist, and a slip was not to be chanced if humanly avoidable. This thumb-joint method was employed whether or not a man used the trigger for firing.

On the second point, I have often been asked why five shots without reloading were all a top-notch gunfighter fired, when his guns were chambered for six cartridges.

The answer is, merely, safety. To ensure against accidental discharge of the gun while in the holster, due to hair-trigger adjustment, the hammer rested upon an empty chamber. As widely as this was known and practiced, the number of cartridges a man carried in his six-gun may be taken as an indication of a man’s rank with the gunfighters of the old school. Practiced gun-wielders had too much respect for their weapons to take unnecessary chances with them; it was only with tyros and would-bes that you heard of accidental discharges or didn’t-know-it-was-loaded injuries in the country where carrying a Colt was a man’s prerogative.”

NOTE: My great grandfather Captain Fred Newton Scofield was a friend to Wyatt and a judge in Tombstone in 1880. Later they went in business together in Bakersfield California. My Uncle was bounced on the knee of Wyatt Earp as he was a frequent visitor to the home of Great Grandpa Scofield.