Suspension of Disbelief

Experts and the Power of Self-Deception

Recently, a friend fretted about what she perceived to be the dismal state of the world, based on the pronouncements of “experts” but, anticipating my response, added, “But you tend to dismiss ‘experts.’” I said she misjudged my sentiments, and that:

“I don’t dismiss experts. I simply don’t worship them. I don’t wish to grant them authoritarian power. And, out of a sense of risk-aversion and a knowledge of history, I want them kept on short leashes. As I wrote sometime back, science is a fine expert witness and a bloody dangerous judge.”

Experts are ordinary human beings, with all the fallibilities that come with membership in our species. Like everyone else, experts sometimes suppress truth and disseminate falsehoods for self-preservation or personal gain. Sometimes, they do so in service to some larger cause. Experts, short on time or resources, may cut corners, publishing information they hope is correct, while knowing it may not be. In all these situations, the expert knows his or her information is or may be false.

More interesting, more likely, and more dangerous are those situations where the expert sincerely believes his or her falsehoods to be correct, owing to the lure of self-deception. Paul Simon’s “The Boxer” sings:

“I have squandered my resistance

For a pocketful of mumbles

Such are promises

All lies and jest

Still a man hears what he wants to hear

And disregards the rest”

I don’t “dismiss” experts but am wary of their tendency to squander their resistance, hearing what they wish to hear and disregarding the rest. Such is the sway that the still small voice of self-deception holds over all of us. And that voice is not muted by a doctorate or academic chair. In Duck Soup (1933), Chico Marx asks Margaret Dumont, “Who ya gonna believe? Me, or your own eyes?” I know enough history (and enough experts) to know that one’s own eyes are often at a distinct disadvantage versus a thing devoutly to be wished.

Self-deception can be conspiratorial, communal, or solitary and can be remarkably persistent. Self-deceived expertise is extraordinarily dangerous when issued blank-check authority by governmental or religious authorities. In Bastiat’s Window, “1,600 Years of Medical Hubris” explored the groupthink that ossified Western medicine between the 2nd and 19th centuries, plus the collectively reinforced misinformation that impeded the proper treatment of autism, ulcers, and prion-borne diseases in the 20th century. In “When Sterilization Was Dogma,”

and I discussed groupthink, eugenics, and contemporary challenges. “Gloomy Saints and Wandering Virtues” recounted how Alexander Graham Bell dispensed nonsense about the heritability of deafness—contradicted by the genetic histories of his mother and his wife.

To illustrate the powers of self-deception, I’ll offer three stories:

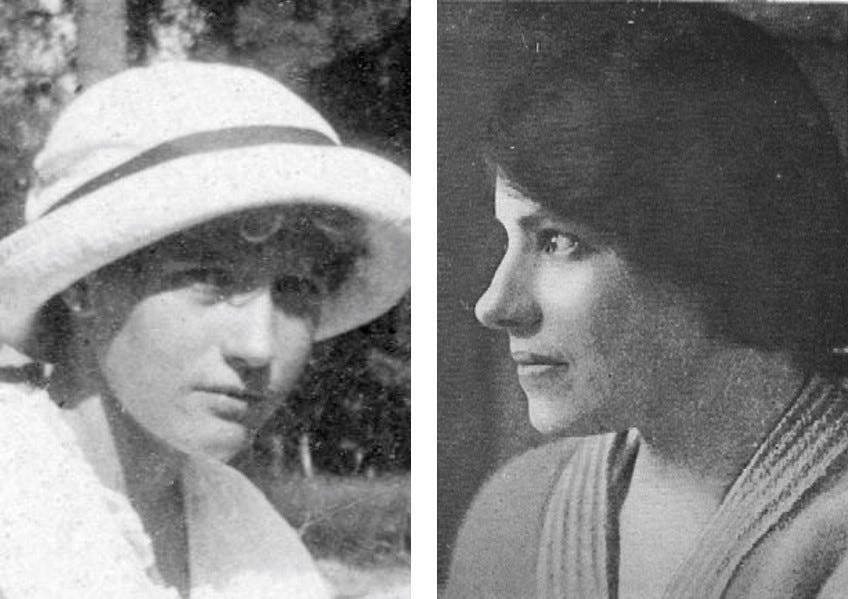

- Anna Anderson, who successfully impersonated Russia’s Grand Duchess Anastasia for over 60 years,

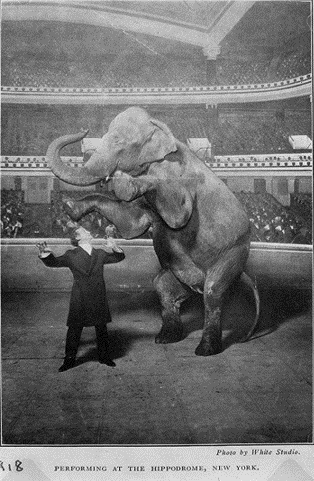

- Harry Houdini, who persuaded thousands of viewers that he could make an elephant vanish from an open stage, and

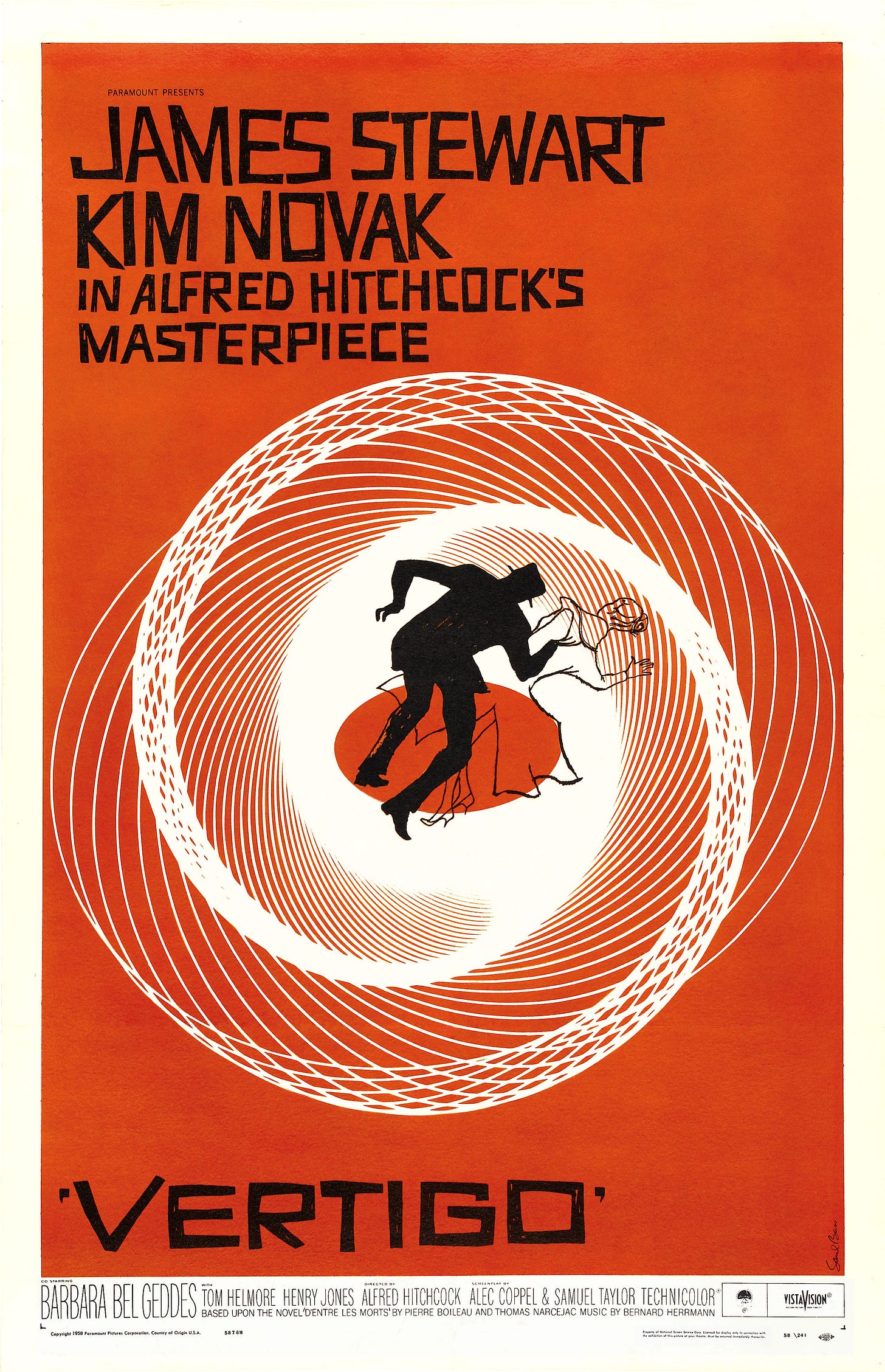

- Scottie Ferguson, the fictional detective in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, who blindly missed the true connection between two women with whom he was destructively in love.

A famous Russian saying advises, “Trust, but Verify” (“Доверяй, но проверяй”/“Doveryai, no Proveryai.”) When I was an undergraduate in Charlottesville, Virginia, in the 1970s, a community of Czarist émigrés seemed to follow a different philosophy: “Trust, Don’t Verify” (“Доверяй, нe проверяй”/“Doveryai, nye Proveryai.”)—at least in the matter of Anna Anderson (Manahan), a.k.a. Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna.

We University of Virginia students often saw Anderson and her husband, Jack Manahan, around town and, for a brief while, I lived two doors down from their beautiful home, which was then surrounded by waist-high weeds, garbage, and an estimated 60 cats. In 1974, I watched then-Governor Jimmy Carter engage in such a remarkably adroit and fluid conversation with a sizable audience that I left saying, “I think that guy will be the next president.” The only moment when Carter was speechless was after Jack Manahan asked him a bizarre, convoluted question about Watergate. (For more on the Manahans, read Jack & Anna: Remembering the Czar of Charlottesville Eccentrics” and watch this video.)

For decades, Anderson alternated between mental institutions and a circle of nobles and celebrities, including pianist/composer Sergei Rachmaninov, who housed her for a while. She came to Charlottesville at the behest of Gleb Botkin, son of Czar Nicholas’s imperial physician, who was murdered along with the Czar and his family. Gleb Botkin had been the real Anastasia’s childhood playmate and swore till his death that Anna Anderson was that playmate. (Botkin was also archibishop of his own Church of Aphrodite.) Anderson attracted the devotion of Russian émigrés, clinging desperately to the belief that one Romanov had survived the hellish slaughter in Yekaterinburg.

But Anna Anderson was not Anastasia, but rather, Franziska Schanzkowska—a Polish factory worker. In 1991, DNA tests demonstrated that Anderson was not related to the Romanovs. A few years later, tests showed that she was related to the Schanzkowskis—a Polish working-class family. (Further tests in 2007 demonstrated conclusively that all seven Romanovs had died at Yekaterinburg.)

For some of Anderson’s enthusiasts, the DNA evidence was sufficient to cause 75+ years of scales to fall from their eyes. Some told interviewers that they finally understood why “Anastasia” could not speak Russian, why she had a German or Polish accent, why her nose was different from Anastasia’s, why she lacked considerable knowledge of the Romanov family and court, why various acquaintances of Anastasia had declared her an imposter in the 1920s, and why the Schanzkowskis had always said that she was their mentally unbalanced sister. How had intelliegent, knowledgeable people from the imperial family’s circle overlooked all of this glaring evidence? Because they wanted the beautiful young Anastasia to have survived, and they wanted Anna Anderson to be that child as an adult. And because Anastasia’s venerators had talked one another into believing an unbelievable fantasy. (Some czarist acolytes apparently still insist that Anderson was Anastasia and that the DNA tests should be discounted along with all of the other inconvenient facts.)

Where Did Jennie Go?

On January 7, 1918, the great magician Harry Houdini performed one of his most celebrated tricks ever on the world’s largest stage—New York City’s Hippodrome. At the climax of his act, he walked Jennie, a five-ton elephant, into a relatively small box (small for an elephant, anyway), closed the box, and had a dozen or so men turn the box slowly around. When the box stopped turning, Houdini opened the box, and the elephant was gone. Where, the audience wondered, had Jennie gone, and how had Houdini spirited her off the vast stage, which was in plain view of the audience?

The precise details of the trick are still debated a century later, but the truth seems to be that the box was much larger than the dimensions that Houdini told the audience—and that the box had an extra room into which Jennie was led while the box was being turned. (A fuller explanation is here.) An audience member with sufficient presence of mind could likely have seen through the false measurements that Houdini had given them. But from all accounts, attendees were uniformly mystified by an astonishing trick.

The trick worked because, as Houdini understood well, the audience wanted it to work. They wanted to go home having witnessed one of the greatest magic performances in history, with no idea how it was done. Unlike the Anastasia venerators, the audience had not arrived with a desire for a disappearing elephant; nor had they talked with one another to fortify this hope. But Houdini understood psychology and the power of self-deception. He understood that 10,000 people would all want Jennie to vanish without a trace—and that almost all would happily overlook evidence to the contrary.

Vertigo: Falling, Falling, Falling

In Vertigo, an emotionally fragile ex-San Francisco police detective, Scottie Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart), falls deeply in love with Madeleine Elster (Kim Novak), a troubled woman who seems to commit suicide before his eyes. Incapacitated by grief and guilt, he suffers a severe mental breakdown and is institutionalized for a time. Later, he meets and strikes up a romantic relationship with Judy Barton (also Kim Novak). His interest in Judy, though, is perverse. Somehow, she reminds him of Madeleine, despite the fact that Judy is brunette, earthy, and plainly dressed, while Madeleine was blonde, elegant, and regally attired. In a sort of demented Henry Higgins maneuver (as in Pygmalion or My Fair Lady), Scottie coerces a resistant Judy into dyeing her hair, replicating Madeleine’s wardrobe, and altering her demeanor and voice to become the resurrection of Madeleine. Her makeover works spectacularly because, in fact, she is Madeleine. The suicide was staged as part of a criminal plot which included murdering the real Madeleine, whom Scottie never met. Ultimately, Judy lets a clue slip, Scottie’s detective skills kick in, and he realizes he has been duped.

When I first saw Vertigo, it didn’t work for me. The screenplay and acting were as good as they get. The cinematography is among the most beautiful ever committed to film. But I had trouble suspending disbelief. It seemed impossible to me that anyone, let alone a detective, would not realize that his “dead” love and a current flame were one and the same. Evolution has given humans remarkable facial and vocal recognition skills, and I couldn’t imagine that someone close to me could hide their identity from me using hair dye, clothes, and vocal stylings.

A few years later, I saw Vertigo once again and recognized it as the masterpiece is it. Perhaps owing to a few years of acquired wisdom, I understood that Scottie was deceived because he wanted to be deceived. He wanted the seemingly dead Madeleine to remain good and pure, rather than an amoral fraud. And he wanted Judy to become the resurrection of that lost love. The truth would shatter both of those wants (as Judy’s slip-up eventually does). With the passage of time, I had intuitively learned that desire can utterly blind one to the obvious.

I was not the only one who was slow to warming up to Vertigo, by the way. Every ten years, the British Film Institute’s Sight and Sound publication polls nearly a thousand critics, academics, and others to compile a list of the greatest films ever made. In 1962, four years after Vertigo’s release, the film was nowhere to be found in the polling results. In 1972, it was voted #17, and then steadily rose: #9 in 1982, #4 in 1992, and #2 in 2002. In 2012, Vertigo was finally rated #1, bumping Citizen Kane down to #2 after 50 years in the top spot. (In 2022, the two were voted #2 and #3 behind a 1972 Belgian/French film with the unwieldy title, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.) My pet theory is that it requires a certain icy bleakness of spirit to allow mere facts to overcome the intense desires for Anastasia’s survival, Jennie’s vanishment, or Madeleine’s purity. In 1962, the world may have just been a tad too upbeat to accept Scottie’s self-deception.

Conclusion

So, to my good friend and correspondent, I do respect experts. I listen to them, I weigh their pronouncements in the balance. But I do not and will not view their words as proof texts. I worry much more about experts who are sincere than about those who are knowing frauds. The latter tend to move on to other frauds or, like Judy Barton, slip up and reveal their dishonesty. The true believer with imposing credentials, on the hand, is much harder to catch, as they have no need to plot out lies. And statements like “97 percent of scientists believe this” is no more persuasive than “97 percent of Houdini’s audience believed that Jennie had somehow been whisked off of the stage.”