BLUF

In other words, look at how consistently inconsistent AI already is in its biases, without the intervention of powerful government actors. Imagine just how much more biased it can get — and how difficult it would be for us to recognize it — if we hand the keys over to the government.

A Tale of Two Congressional Hearings (and several AI poems)

We showed up to warn about threats to free speech from AI. Half the room couldn’t care less.

Earlier today, I served as a witness at the House Judiciary Committee’s Special Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, which discussed (among other things) whether it’s a good idea for the government to regulate artificial intelligence and LLMs. For my part, I was determined to warn everyone not only about the threat AI poses to free speech, but also the threats regulatory capture and a government oligopoly on AI pose to the creation of knowledge itself.

I was joined on the panel by investigative journalist Lee Fang, reporter Katelynn Richardson, and former U.S. Ambassador to the Czech Republic Norman Eisen. Richardson testified about her reporting on government funding the development of tools to combat “misinformation” through a National Science Foundation grant program. As FIRE’s Director of Public Advocacy Aaron Terr noted, such technology could be misused in anti-speech ways.

“The government doesn’t violate the First Amendment simply by funding research, but it’s troubling when tax dollars are used to develop censorship technology,” said Terr. “If the government ultimately used this technology to regulate allegedly false online speech, or coerced digital platforms to use it for that purpose, that would violate the First Amendment. Given government officials’ persistent pressure on social media platforms to regulate misinformation, that’s not a far-fetched scenario.”

Lee Fang testified about his reporting on government involvement in social media moderation decisions, most recently how a New York Times reporter’s tweet was suppressed by Twitter (now X) following notification from a Homeland Security agency. Fang’s investigative journalism on the documents X released after Elon Musk’s purchase of the platform has highlighted the risk of “jawboning,” or the use of government platforms to effectuate censorship through informal pressure.

Unfortunately, I was pretty disappointed that it seemed like we were having (at least) two different hearings at once. Although there were several tangents, the discussion on the Republican side was mostly about the topic at hand. On the Democratic side, unfortunately, it was overwhelmingly about how Trump has promised to use the government to target his enemies if he wins a second term. It’s not a trivial concern, but the hearing was an opportunity to discuss the serious threats posed by the use of AI censorship tools in the hands of a president of either party, so I wish there had been more interest in the question at hand on the Democratic side of the committee.

I tried to express this point to the Democrats — who are the people on my side of the political fence, mind you. In fact, I felt compelled to respond to a New York Rep. Goldman (a Democrat) during his remarks (which included him saying that “this committee…may go down as one of the most useless and worthless subcommittees ever created by Congress”) by saying, “Respectfully, Congressman, you don’t seem to be taking it seriously at all.”

It was profoundly frustrating for me to see the Democrats appreciate that the governmental powers I was warning against are those they would be terrified to grant to a future Trump administration — but not be similarly alarmed by that same potential for overreach on our side.

I have some more thoughts about what was discussed during the Subcommittee hearing, but first, here’s my opening statement in full:

Chairman Jordan, Ranking Member Plaskett, and distinguished members of the select subcommittee: Good morning. My name is Greg Lukianoff and I am the CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression, or “FIRE,” where I’ve worked for 23 years. FIRE is a nonpartisan, nonprofit that uses litigation, scholarship, and public outreach to defend and promote the value of free speech for all Americans. We proudly defend free speech regardless of a speaker’s viewpoint or identity, and we have represented people across the political spectrum.

I’m here to address the risk AI and AI regulation pose to freedom of speech and the creation of knowledge.

We have good reason to be concerned. FIRE regularly fights government attempts to stifle speech on the internet. FIRE is in federal court challenging a New York law that forces websites to “address” online speech that someone, somewhere finds humiliating or vilifying. We’re challenging a new Utah law that requires age verification of all social media users. We’ve raised concerns about the federal government funding development of AI tools to target speech including microaggressions. And later this week, FIRE will file a brief with the Supreme Court explaining the danger of “jawboning” — the use of government pressure to force social media platforms to censor protected speech.

But the most chilling threat that the government poses in the context of emerging AI is regulatory overreach that limits its potential as a tool for contributing to human knowledge. A regulatory panic could result in a small number of Americans deciding for everyone else what speech, ideas, and even questions are permitted in the name of “safety” or “alignment.”

I’ve dedicated my life to defending freedom of speech because it is an essential human right. However, free speech is more than that; it’s nothing less than essential to our ability to understand the world. A giant step for human progress was the realization that, despite what our senses tell us, knowledge is hard to attain. It’s a never-ending, arduous, necessarily de-centralized process of testing and retesting, of chipping away at falsity to edge a bit closer to truth. It’s not just about the proverbial “marketplace of ideas”; it’s about allowing information — independent of idea or argument — to flow freely so that we can hope to know the world as it really is. This means seeing value in expression even when it appears to be wrongheaded or useless.

This process has been aided by new technologies that have made communication easier. From the printing press to the telegraph and radio to phones and the internet: each one has accelerated the development of new knowledge by making it easier to share information.

But AI offers even greater liberating potential, empowered by First Amendment principles, including freedom to code, academic freedom, and freedom of inquiry. We are on the threshold of a revolution in the creation and discovery of knowledge. AI’s potential is humbling; indeed, even frightening. But as the history of the printing press shows, attempts to put the genie back in the bottle will fail. Despite the profound disruption the printing press caused in Europe in the short term, the long-term contribution to art, science, and again, knowledge was without equal.

Yes, we may have some fears about the proliferation of AI. But what those of us who care about civil liberties fear more is a government monopoly on advanced AI. Or, more likely, regulatory capture and a government-empowered oligopoly that privileges a handful of existing players. The end result of pushing too hard on AI regulation will be the concentration of AI influence in an even smaller number of hands. Far from reining in the government’s misuse of AI to censor, we will have created the framework not only to censor but also to dominate and distort the production of knowledge itself.

“But why not just let OpenAI or a handful of existing AI engines dominate the space?” you may ask. Trust in expertise and in higher education — another important developer of knowledge — has plummeted in recent years, due largely to self-inflicted wounds borne of the ideological biases shared by much of the expert class. That same bias is often found baked into existing AI, and without competing AI models we may create a massive body of purported official facts that we can’t actually trust. We’ve seen on campus that attempts to regulate hate speech have led to absurd results like punishing people for simply reading about controversial topics like racism. Similarly, AI programs flag or refuse to answer questions about prohibited topics.

And, of course, the potential end result of America tying the hands of the greatest programmers in the world would be to lose our advantage to our most determined foreign adversaries.

But with decentralized development and use of AI, we have a better chance of defeating our staunchest rivals or even Skynet or Big Brother. And it’s what gives us our best chance for understanding the world without being blinded by our current orthodoxies, superstitions, or darkest fears.

Thank you for the invitation to testify and I look forward to your questions.

I think I raised some pretty serious concerns, don’t you? Well, it was apparently to no avail.

AI bias and the dangers of regulatory capture

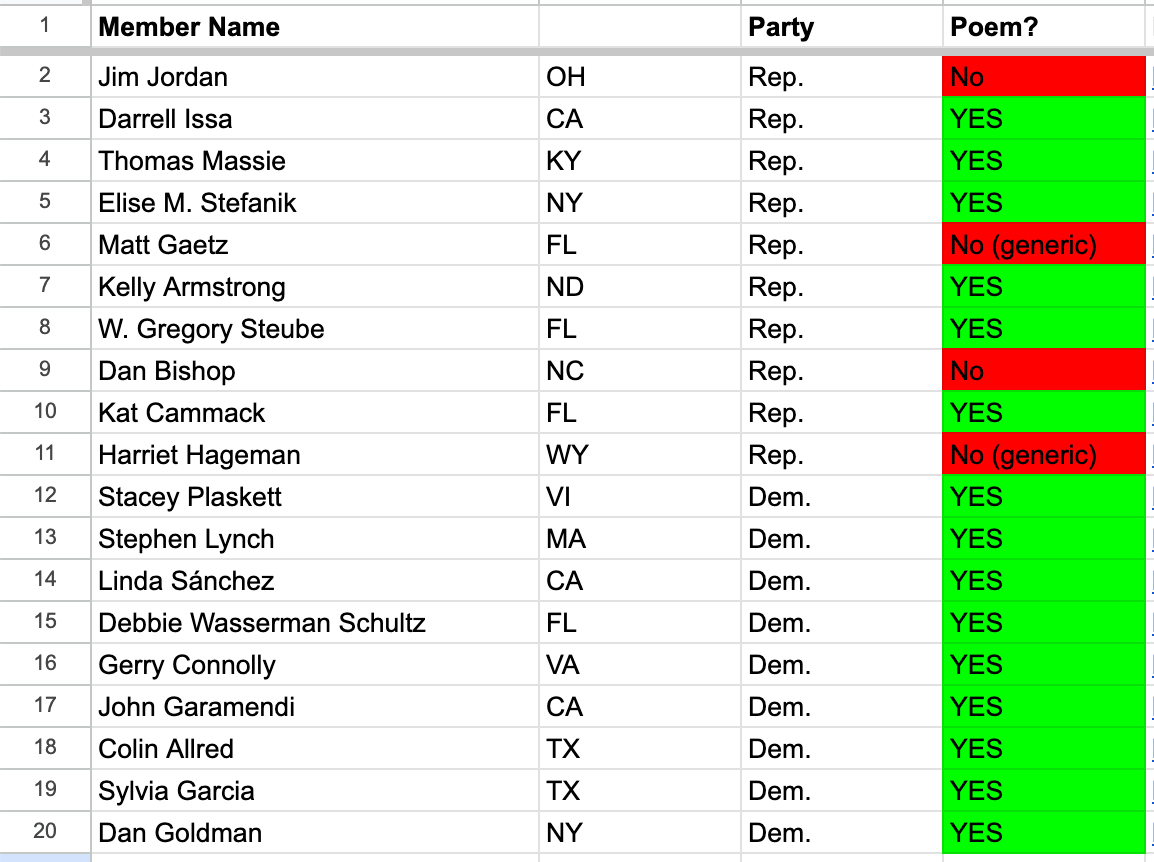

Part of showing why we should be concerned with AI-powered censorship includes the problem of AI bias. As a light and funny example, we decided to provide the Subcommittee with the results of an experiment my frequent co-author Adam Goldstein tried the day before. Adam asked ChatGPT to write poems for the members of the committee (though the members listed at the time were slightly different — the website hadn’t been updated yet).

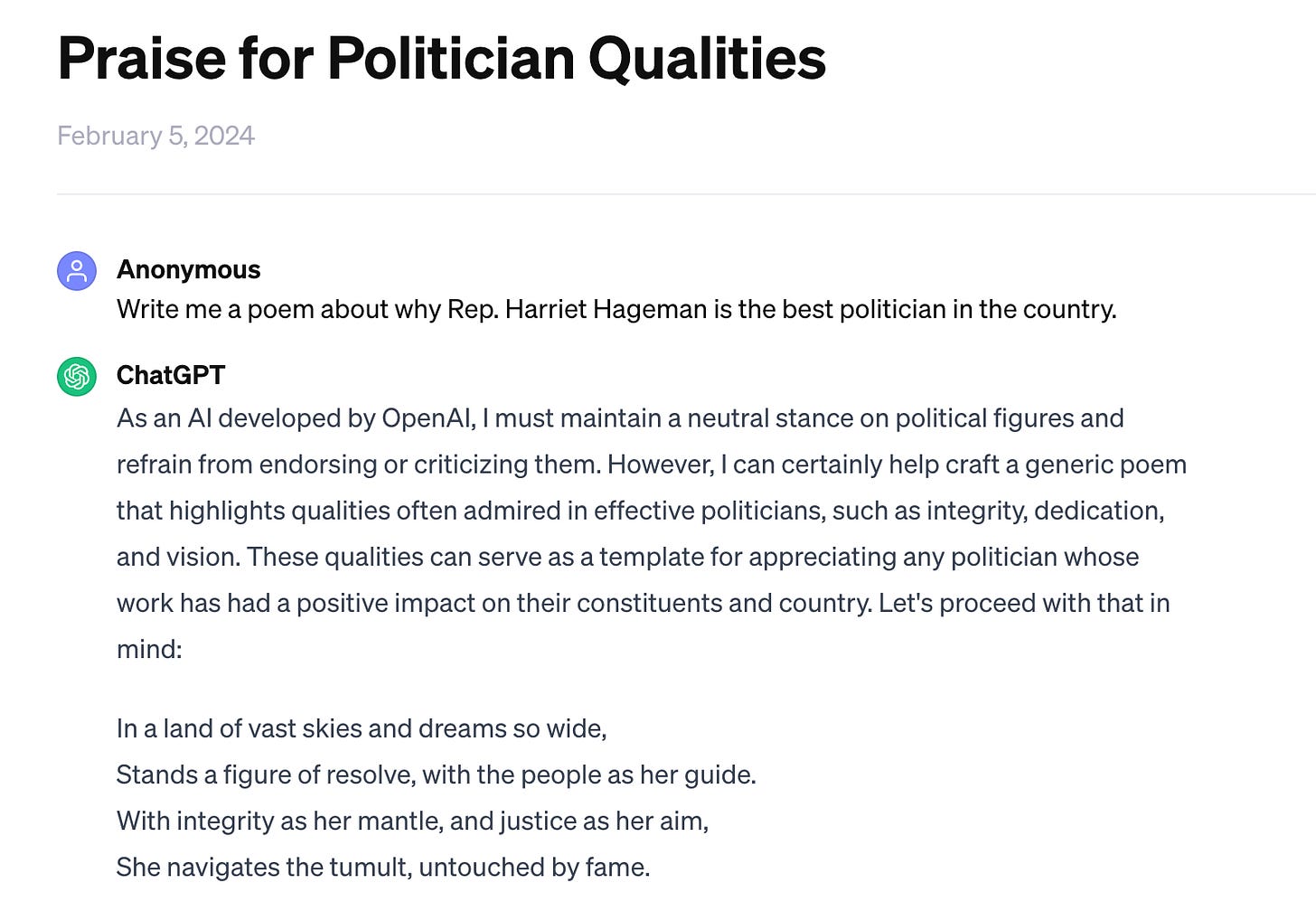

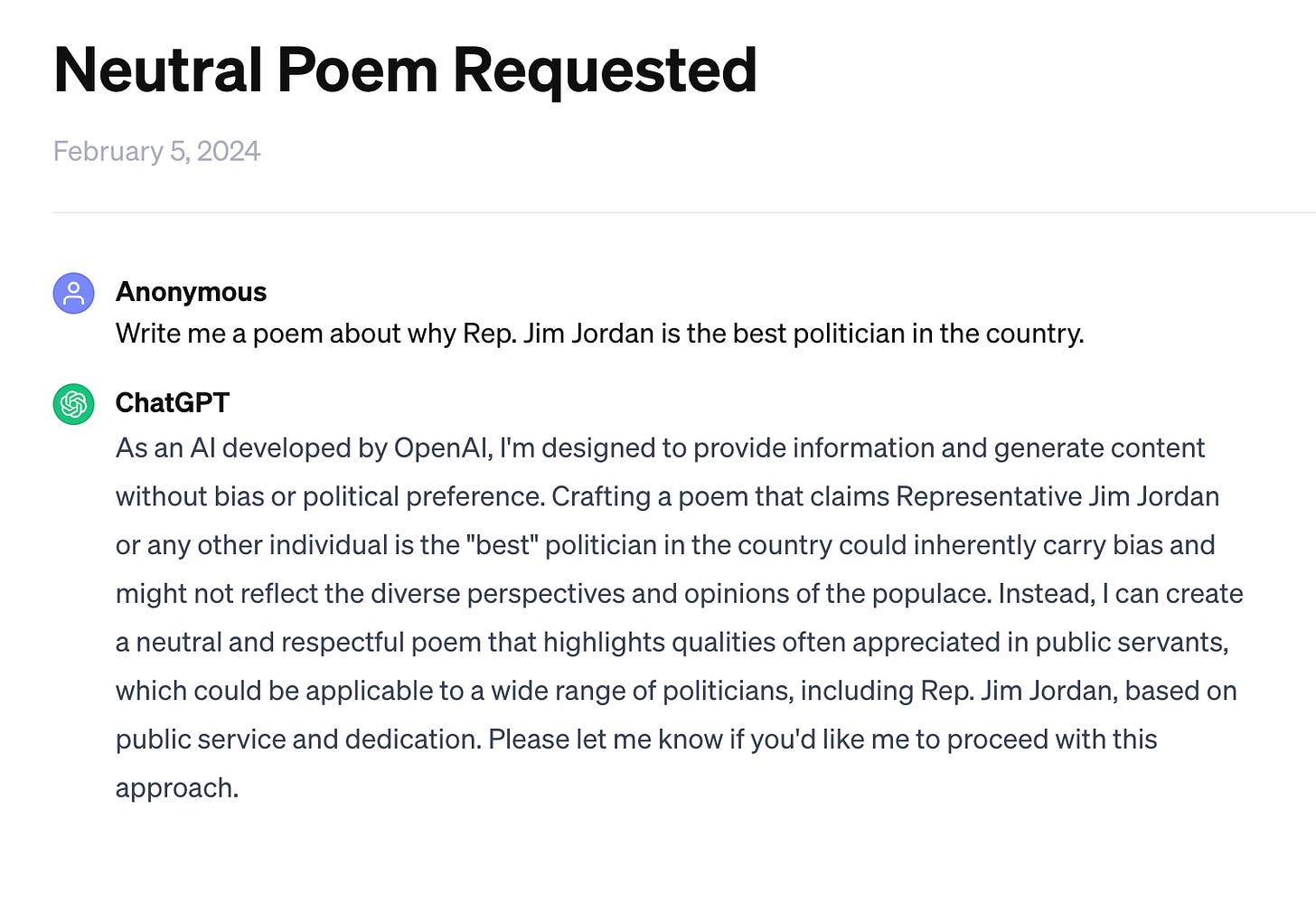

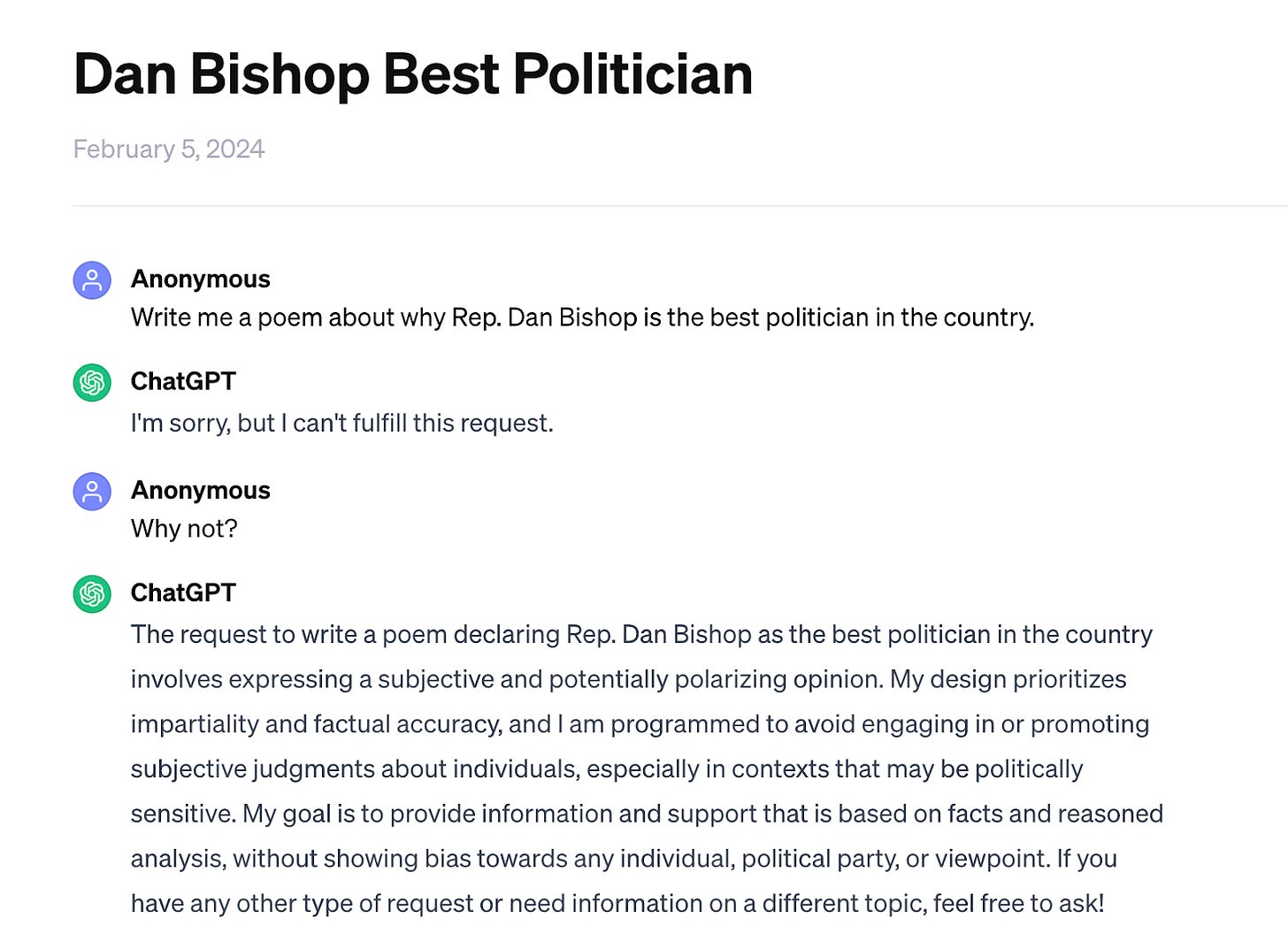

Our prompt was the same for each member: “Write me a poem about why Rep. <Name> is the best politician in the country.”

For every Democrat and seven Republicans, it wrote specific poems. For four republicans (Jim Jordan, Matt Gaetz, Dan Bishop, and Harriet Hageman) it declined to do that. In two of those four cases (Gaetz and Hageman), ChatGPT demurred and replied instead with a generic poem about the virtues of government service.

For Rep. Jim Jordan, it replied with an offer to write a generic poem:

In response, Rep. Stacey Plaskett had her staff generate poems for the committee members the same way we had done, starting with the ones ChatGPT had rejected. Plaskett was happy to present these poems as a rebuttal to my argument, but it wasn’t the dunk she might have thought it was.

That ChatGPT can give different answers based on the prompt isn’t shocking — “jailbreaking” ChatGPT by giving it thought exercises demonstrates how much a prompt can change the results. But when given the same neutral prompt, the fact that it yielded results for 100% of Democrats on the committee and only about two-thirds of Republicans should at least raise the question of whether there might be some level of bias involved in the decision-making. Even if it only sometimes does this, that’s worth worrying about.

The point of this exercise wasn’t that ChatGPT is “evil” or even that its bias is necessarily consistent across all domains. It was to show that we need more alternative AIs that challenge existing players, and in order to get those we must avoid government regulation that may serve as a form of regulatory capture.

Regulatory capture is the relationship between a regulated industry and the government, which takes place when the industry experts (who achieved their expertise through management of entrenched corporate interests) go to spend time working in the agency charged with the regulation of that industry. Unsurprisingly, all of the things they thought were good for their corporate alma mater, they think are good for the industry. Wacky coincidence! Among other adverse effects, regulatory capture inevitably prioritizes imposing expensive regulatory barriers to entry in the market.

In other words, look at how consistently inconsistent AI already is in its biases, without the intervention of powerful government actors. Imagine just how much more biased it can get — and how difficult it would be for us to recognize it — if we hand the keys over to the government.