Why this is even a question is what’s amazing;

“Unrealized” gains – emphasis on the word unrealized –are not ‘income’ since they haven’t been paid or credited.

This is simply the goobermint exercising power over people. They don’t need our money, they print it at leisure. Taxing keeps the people from using for their own purposes.

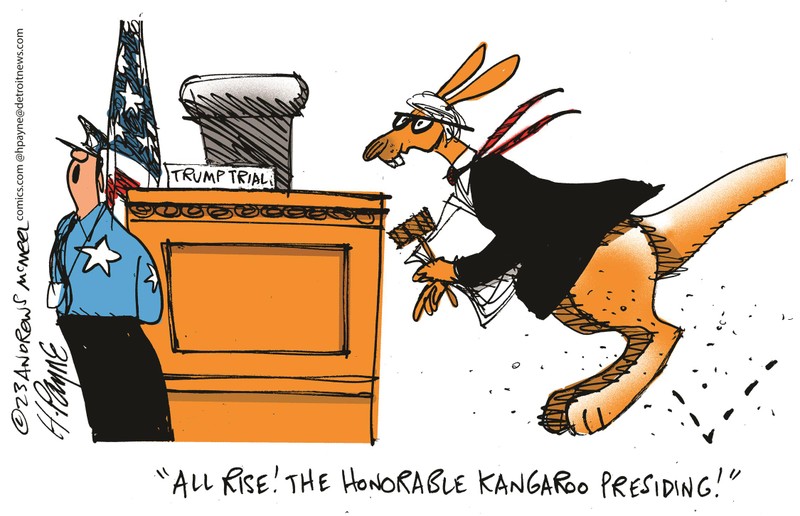

The stakes are high as Supreme Court considers this obscure, unconstitutional tax

Word games are usually fun. They become less fun, however, when the government uses them to levy unjust and unconstitutional taxes from the citizenry.

The Supreme Court is set to determine whether Congress , for the purposes of taxation, may classify unrealized capital gains as “income.” Should the justices rule in Moore vs. United States rule against the plaintiffs, the federal government effectively would gain seismic new powers to tax almost any property from which it hopes to extract revenue. This would conflict directly with the Constitution ’s plain text and original meaning.

Charles and Kathline Moore, the case’s plaintiffs, have challenged an obscure provision in 2017’s landmark Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. This provision created a “mandatory repatriation tax” (MRT), which subjects Americans who own stock in foreign companies to a one-time tax on some of those companies’ earnings over the previous 30 years. Congress classified it as an “income” tax.

The Moores in 2006 purchased a 13% share of an Indian company, KisanKraft, that provides farming equipment to impoverished regions. Since then, they never have received any dividend or other form of compensation or profit from this investment. They have seen no “income.” Nonetheless, they found themselves subjected to the MRT.

“The Moores were … taxed as if KisanKraft … had … distributed to the Moores a dividend worth 13% of KisanKraft’s total earnings since 2006,” the Cato Institute explains in its amicus brief.

Beginning with dictionary definitions, the government’s arguments wilt. “Income has a plain and longstanding meaning: for something to be ‘in-come,’ it must, in some way, ‘come in,’” as the Chamber of Commerce writes. Moreover, early-1900s legal authorities believed “income” necessarily implied realization of gains. Put differently, “income” by nature requires the taxable money to become separated from the capital asset; an asset’s increased value cannot alone suffice. This interpretation corresponds with 19th-century caselaw, discussions surrounding the 16th Amendment’s ratification, contemporaneous state statutes, the Revenue Act of 1913 (which instituted the newly constitutional income tax), and subsequent Supreme Court precedent.

The Framers worried much about abusive federal taxation, and the Constitution originally disallowed Congress to institute any direct tax not apportioned based on state population. The 16th Amendment (ratified in 1913) exempted income taxes from this restriction. Far from a blanket mandate, this amendment’s drafters and ratifiers intended it as a defined carveout to authorize a specific sort of tax.

Only if the Supreme Court adopts the government’s bastardized definition of “income” can the non-apportioned MRT stand.

Further, the MRT required U.S. shareholders to pay tax on foreign companies’ earnings dating back to 1987. Demanded a percentage of 30-year-old earnings (which, to be clear, are better labeled simply as “private property”) resembles more a property tax, taking, or a confiscation than a traditional tax.

Indulging congressional whim by expanding this definition radically (as the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit did when it ruled against the Moores) greatly increases the federal government’s de facto taxation powers. “Without the guardrails of a realization component, the federal government has unfettered latitude to redefine ‘income’ and redraw the boundaries of its power to tax without apportionment,” the outnumbered Ninth Circuit judge Patrick Bumatay argued in dissent.

Indeed, prominent politicians such as President Joe Biden already have advocated an unrealized capital gains tax; the president’s latest budget proposal featured one on wealth exceeding $100 million. A mistaken Supreme Court decision would feed this effort and far worse ones.

“The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined,” James Madison stated in Federalist No. 45.

However, if the Supreme Court in Moore rules that Congress — simply by adopting erroneous interpretations of legally settled terminology — can arrogate to itself vast authorities, an important constitutional guardrail against tyranny would effectively have no force.