No matter what SloJoe babbles on about ‘his’ 1994 gun ban, the facts are:

The Data files for the data used below is available here.

A large amount of research has been done on the federal assault weapons ban that was in effect from 1994 to 2004. It has consistently found no statistically significant impact on mass public shootings or any other type of crime.

This holds true even for research funded by the Clinton administration. Criminology professors Chris Koper and Jeff Roth concluded in a 1997 report for the National Institute of Justice, “The evidence is not strong enough for us to conclude that there was any meaningful effect (i.e., that the effect was different from zero).” Messrs. Koper and Roth suggested that it might be possible to find a benefit after the ban had been in effect for more years. In 2004, they published a follow-up NIJ study with fellow criminologist Dan Woods. They found: “We cannot clearly credit the ban with any of the nation’s recent drop in gun violence. And, indeed, there has been no discernible reduction in the lethality and injuriousness of gun violence.”

Dr. John Lott and others have done similar research on both state and federal assault weapons bans. They’ve found no evidence that any such ban reduced the frequency or deadliness of mass public shootings or had a beneficial impact on any other crime rate. The third edition of “More Guns, Less Crime” (University of Chicago Press, 2010) examined the impact of federal and state assault weapon bans both before, during, and after the federal ban was in effect.

Even a 2014 survey by the left-leaning ProPublica concluded that despite some claims by Democratic politicians, there was no compelling evidence that the federal assault weapons ban had any impact on any type of crime.

In looking at mass public shootings, most researchers have used the traditional FBI definition. And we have also done so in all of our posts on mass public shootings (e.g., here, here, here, and here). There are several parts to this definition.

- The official FBI definition of mass public shootings excludes “shootings that resulted from gang or drug violence” or that occurred in the commission of another crime such as robbery. It isn’t that gang deaths aren’t important, but just that the causes and solutions are dramatically different from the type of mass public shootings at schools, movie theaters and malls where the point of the attack is simply to kill as many people as possible. Indeed, the amount of coverage given to these different events shows that the media also treats these two types of cases quite differently.

- The FBI only includes shootings in “public places” such as commercial areas (malls, stores, and other businesses), schools and colleges, open spaces, government properties (including military bases and civilian offices), houses of worship, common areas at apartment buildings, and healthcare facilities. [Residences were included in the total deaths only when “where casualties occurred inside a private residence before a shooter moved to a public area, those incidents were categorized at the location where the public was more at risk.” For example, their cases would involve a residence and then a school.]

- From the 1980s to 2013, the original FBI definition of “mass killings” had been “four or more victims slain, in one event, in one location,” not including the offender in the victim count (CRS, July 30, 2015). In 2013, the definition was changed to “three or more killings.” The vast majority of academics have continued to use the four-or-more definition. This includes researchers such as James Alan Fox. See also studies from years ago such as, “The Impact of Right-to-Carry Concealed Firearm Laws on Mass Public Shootings,” (Grant, Kovandzic, Moody, Homicide Studies, Nov. 1, 2002). Even groups such as Bloomberg’s Everytown for Gun Safety, which Snopes cites approvingly, has recently used the four-or-more definition.

Some recent work by Louis Klarevas has gotten a lot of attention for claiming that the 1994-2004 Assault Weapon ban supposedly reduced the number of mass shootings. While his research isn’t peer-reviewed research, we will still spend some time discussing it. Klarevas starts by making an unusual decision in terms of how he limits his research to shootings with 6 or more fatalities. We don’t know of any other study that does this, and Klarevas doesn’t provide an explanation. Nor does he explain why he mixes together public shootings with gang shootings. Klarevas merely uses the alternative phraseology of “high-fatality” mass shootings.

Here are two graphs, the first by the Washington Post and the second by former Labor Secretary Robert Reich, that make use of Klarevas’ numbers.

Academics wouldn’t make the types of comparisons that Klarevas makes. They would see how death rates changed in states where the federal ban actually affected the ability of citizens to own assault weapons. Then they would compare these states with other states where the law effectively remained unchanged because state-level bans were already in place. That is the way Koper and Roth did it in their studies, as did Lott, and it resulted in not finding any impact from assault weapon bans.

The rate of mass shootings or mass public shootings may go up and down for many reasons over time. But if the assault weapons ban reduced these attacks, the share of attacks committed with “assault weapons” should have decreased. If the gun control advocates are right, banning assault weapons ought to reduce attacks or murders committed with assault weapons.

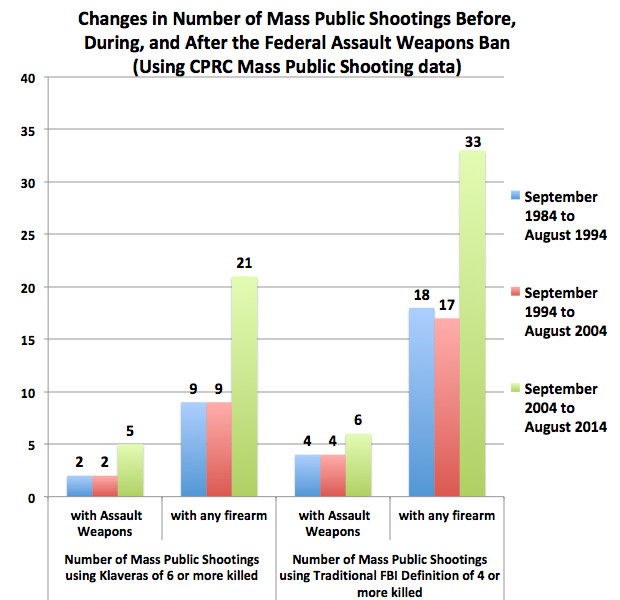

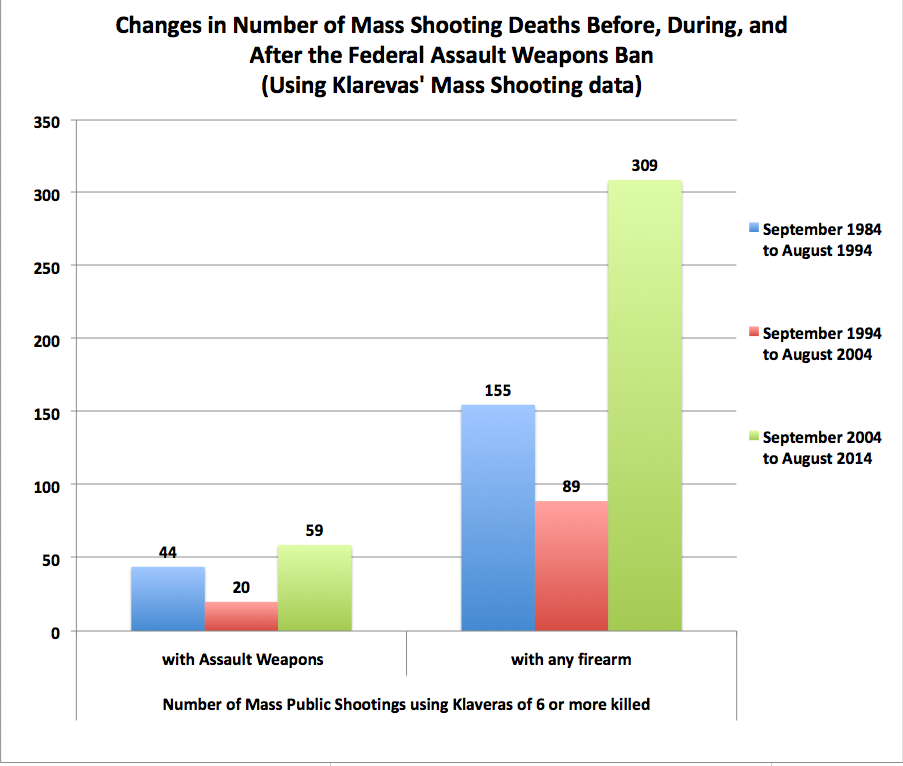

But just for the sake of argument, let’s initially follow Klarevas in looking at the total number of attacks before, during, and after the assault weapons ban. We will use the cases that Klarevas identifies in his book as mass shootings (here and here) as well as mass public shootings collected by Mother Jones and the CPRC. Klarevas doesn’t provide any breakdown for only shootings committed with assault weapons, even though the assault weapons ban is the subject of his research.

In an email to writer Jon Stokes, Klarevas identified seven mass shootings with assault weapons over the ten years from January 1984 though 1993 (the earliest being the San Ysidro, California attack on a McDonald’s in July 1983). Using Klarevas’ definition, we identified two cases with assault weapons in the ten years when the federal Assault Weapons Ban was in effect from September 1994 to September 2004 (the Columbine shooting in 1999 and an attack in Wakefield, Massachusetts in 2000 with an AK-47). Even using Klarevas’ cases, our numbers differ slightly from his because we look at the 10-year periods from September 1984 to August 1994, September 1994 to August 2004, and September 2004 to September 2014. We only include part of 1984 and 2014 in our time range, whereas Klaveras includes both years in their entirety.

The Mother Jones dataset also includes cases that don’t meet the FBI’s definition of Mass Public Shootings, but since it is a widely cited source of cases we have used it for our comparisons.

No matter which dataset we use, the number of mass shootings committed with assault weapons is very small compared to the total number of mass shootings. Looking at the number of attacks with assault weapons, the Mother Jones list shows a difference of only one or two between each of the three, ten-year periods. This holds true whether we use the traditional FBI definition of 4-or-more killed or Klarevas’ definition of 6-or-more killed. The CPRC data is similar, showing differences of either zero, two, or three attacks. None of these changes are large enough to prove the ban had any impact on attacks.

Looking at attacks committed with any type of firearm, the differences that Klarevas finds between the pre-ban and ban periods either completely disappears or becomes just one or two attacks.

When we instead look at the number of fatalities, we see again that the results are very sensitive to how Klarevas sets it up. When looking at mass public shootings, there is very little evidence of a significant drop in deaths from the assault weapons ban. Using the Mother Jones list of cases, we find that compared to the preceding ten years, there is drop of only four deaths in the decade of the assault weapons ban. That comes to 0.4 fewer deaths per year. The CPRC data actually shows a slight increase in deaths from the ban when it was in effect.

There is a similar pattern in deaths from mass shootings with 6 or more fatalities. However, the difference between pre-ban and ban fatalities is reduced when examining cases with 4 or more fatalities.

As we mentioned before, while it still doesn’t account for the fact that the federal law didn’t change the law in all states, looking at the share of attacks or deaths specifically from assault weapons seems a much more useful way of testing Klarevas’ and other gun control advocates’ claims. But whether we use Klarevas’ list of cases and definition of mass shootings or the Mother Jones or CPRC lists and definitions, none of the results are consistent with what Klarevas would predict. The share of attacks using assault weapons should be lowest during the federal assault weapons ban. For both Klarevas and Mother Jones, there was a continual drop over time in the share of attacks committed with assault weapons. In both cases, the ten years after the end of the assault weapons ban (September 2004 to August 2014) saw the lowest share of shootings using assault weapons.

The same analysis can be done of the share of mass shooting and mass public shooting deaths from assault weapons. Again, Klarevas’ data shows a continual decline over time. The Mother Jones and CPRC data show even steeper declines. Instead of the decade with the assault weapons ban showing the lowest share of deaths from assault weapons, the pattern is clearly the exact opposite of what gun control advocates would predict. This is true whether one uses the traditional FBI definition of 4-or-more killed or Klarevas’ definition of 6-or-more killed.

“Arbitrariness”

Klarevas has claimed that Lott’s definition of mass public shootings was “arbitrary.” But Lott was using the traditional FBI definition, and the point of doing so is to focus only on the sorts of attacks that get the attention of the news media. These attacks are intended to kill people in public places to generate fear and media attention. But Klarevas doesn’t explain what he thinks is wrong with the FBI definition.

In any case, as we have just shown, even Klarevas own numbers don’t show that both the share of attacks and deaths from mass shootings is not at its lowest during the federal assault weapon ban. Instead, his own numbers show a continual decline over time. This is not consistent with his theory.

Conclusion

To do a proper analysis, one has to consider that some states had assault weapons bans both before and after the federal ban. We want to compare these states with those where the federal law actually imposed a new ban. How did changes in the number of attacks in one type of state compare to the changes in the other type of state?

Even if one doesn’t follow this approach, it still makes more sense to look at the number of attacks or deaths from assault weapons, and compare those changes with the changes for all firearms. When we do so, even Klarevas’ own definition of mass shootings doesn’t support his prediction that the federal ban caused a decrease in attacks and deaths. And using Mother Jones or CPRC data, we find evidence for the opposite of what Klarevas would predict about deaths from mass shootings.

Looking at just the number of attacks or deaths, as Klarevas wants people to do, shows why he looked at all attacks with firearms and not specifically at attacks using assault weapons. It explains why he looks at mass shootings with six or more deaths, and not at mass public shootings using the traditional FBI definition of 4-or-more deaths. While Klarevas describes cases that meet the FBI’s definition of mass public shootings, he doesn’t account for why he applies the FBI definition to mass shootings but not to mass public shootings. He provides no explanation for why he only picks cases where 6 or more people have died.