BLUF

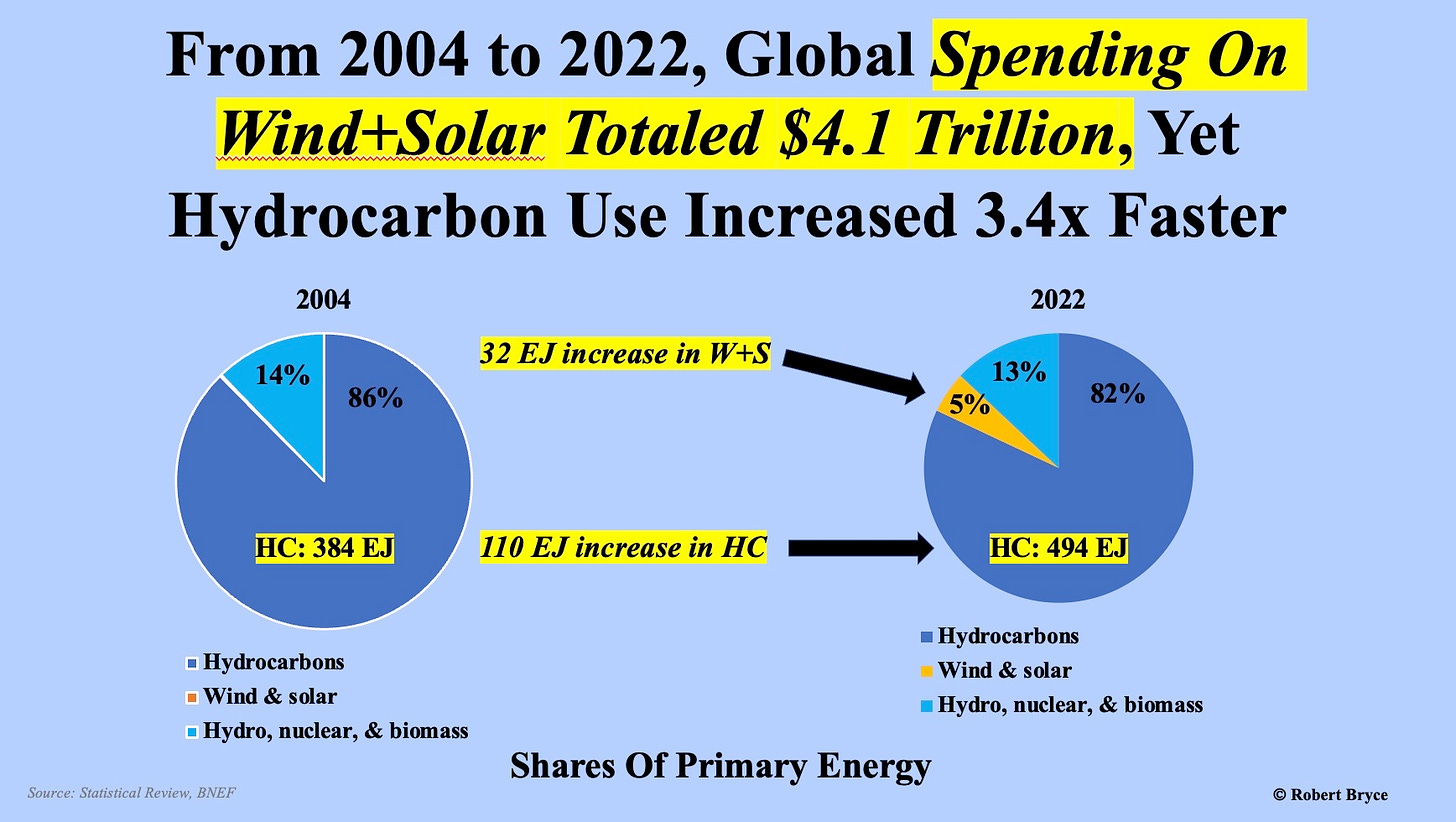

One final point: imagine how much further along the world would be today if the $4.1 trillion spent on wind and solar over the past 18 years had, instead, been spent on developing and deploying the next generation of nuclear power plants. That would be an energy transition worth writing about.

We are inundated with claims about the “energy transition.”

In February, E&E News, reporting on the State of the Union speech said, “President Joe Biden laid out his vision for the energy transition Tuesday night.” In March, a reporter for Politico declared “The U.S. energy transition is well underway.”

Also in March, during a speech at the CERAWeek conference in Houston, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said that “As this transition progresses, our energy mix will change.” Or consider the March 9 press release from the White House, which said “The Administration is continuing to implement the Inflation Reduction Act, which is already galvanizing our clean energy transition and making clean and energy efficient technologies more affordable for American families.”

I could list many more examples like the ones above. But the hard truth is this: the energy transition isn’t. The numbers from the just-released Statistical Review of World Energy show, once again, that despite rapid growth in wind and solar, those two forms of energy are not even keeping pace with the growth in hydrocarbons. That’s true both globally and in the U.S.

And here’s the key point: hydrocarbons are prevailing despite staggering amounts of spending on wind and solar. According to a January report by Bloomberg New Energy Finance, some $6.7 trillion was spent on alt-energy globally between 2004 and 2022, with the vast majority of that, some $4.8 trillion spent on renewables. And the vast majority of that $4.8 trillion — about $4.1 trillion — was spent on wind and solar.

I’ll come back to the U.S. numbers — which like the global numbers, show hydrocarbon growth outstripping wind and solar — in a moment.

Before I do so, it’s important to provide some context and to understand why we are hearing so much — call it what it is, propaganda — about the energy transition.

First, the context. Yes, wind and solar are growing rapidly. In 2022, nearly all of the growth in global electricity generation (about 645 terawatt-hours) was met by the surge in wind and solar production, which grew by 251 and 263 TWh respectively. Global wind output grew by 13% in 2022 and solar increased by 24%. The U.S. saw almost identical percentage increases, with wind and solar generation growing by 15% and 24%, respectively. Those are impressive increases. As the EIA reported on March 27, in the U.S., “generation from renewable sources — wind, solar, hydro, biomass, and geothermal — surpassed coal-fired generation in the electric power sector for the first time.” It also noted that generation from all renewables “surpassed nuclear generation for the first time in 2021.”

These increases are important. But electricity only represents about a fifth of final energy demand. (Final energy, as Hannah Ritchie of Our World in Data explains, is what “a consumer buys and receives, such as electricity in their home, heating, or petrol at the fuel pump.”) So if growth in hydrocarbons is outstripping the growth in wind and solar, why are we being flooded with claims about the energy transition? The short answer: it’s part of a media campaign that has surged under the Biden Administration.

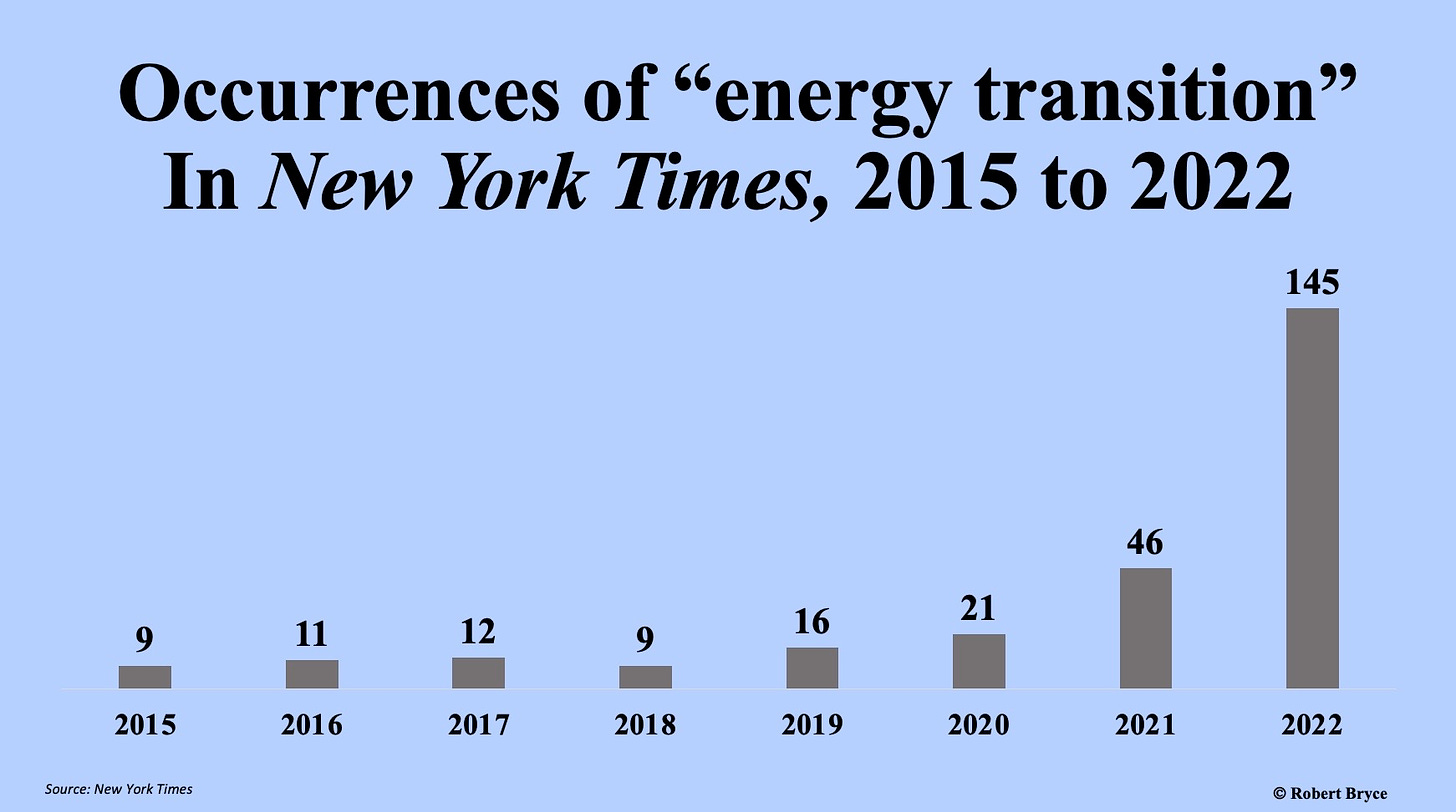

Evidence of the marketing effort can be seen in the number of times the phrase in question has appeared in the New York Times over the past few years. (Hat tip to Roger Pielke Jr., who used this to illustrate a media trend. If you haven’t subscribed to his Substack, you should. Roger published a good piece on the energy transition on Thursday.) As can be seen in the graphic above, from 2015 to 2020, “energy transition” occurred only a few times per year. But in 2021, the year Biden took office, the mentions doubled, and then tripled to 146 mentions in 2022.

The energy transition claims are increasing because that narrative is relentlessly promoted by alt-energy NGOs like the Rocky Mountain Institute (2022 revenue: $115 million) that have massive budgets and scads of sympathetic reporters at legacy media outlets. Those NGOs are part of the anti-industry industry, which is collecting untold millions of dollars in dark money to push claims about the energy transition and the fiction that the global economy can be run solely on wind, solar, batteries, and a dollop of hydropower and hopium.

Last month, the Rocky Mountain Institute published a report which claimed “this is the pivotal decade in the energy transition,” and that “solar and EVs will rise to dominate sector sales by 2030” and renewables will hit “price tipping points in every major area of energy demand.”

It’s essential to note that the Colorado-based NGO has been leading the effort to implement a nationwide ban on the use of natural gas in homes and businesses. The group is also a leading recipient of dark money. According to its annual report, the group got at least $1 million in 2022 from Climate Imperative Foundation, the secretive NGO (2021 revenue: $221 million) that I wrote about in The Billionaires Behind The Gas Bans. RMI also got at least $1 million from one of the biggest dark money climate NGOs, the ClimateWorks Foundation (2021 revenue: $366 million). In addition, RMI got at least $1 million from the Bezos Earth Fund, Bloomberg Philanthropies, and Breakthrough Energy, as well as at least $500,000 from another big dark-money NGO, the Energy Foundation.

Despite the fortunes being spent by the climate claque to promote claims about renewables and the energy transition, global hydrocarbon use and CO2 emissions continue to rise. That’s also true here in the U.S.

In 2022, the U.S. had the world’s third-largest increase in CO2 emissions, 57 megatons. (U.S. emissions last year totaled 4,826 Mt.) The U.S. followed only Indonesia (172 Mt) and India (131 Mt) in that category. China’s emissions fell slightly, by 0.1% or 13 Mt, in 2022. That said, China’s emissions are, by far, the biggest in the world, at 10,550 Mt.

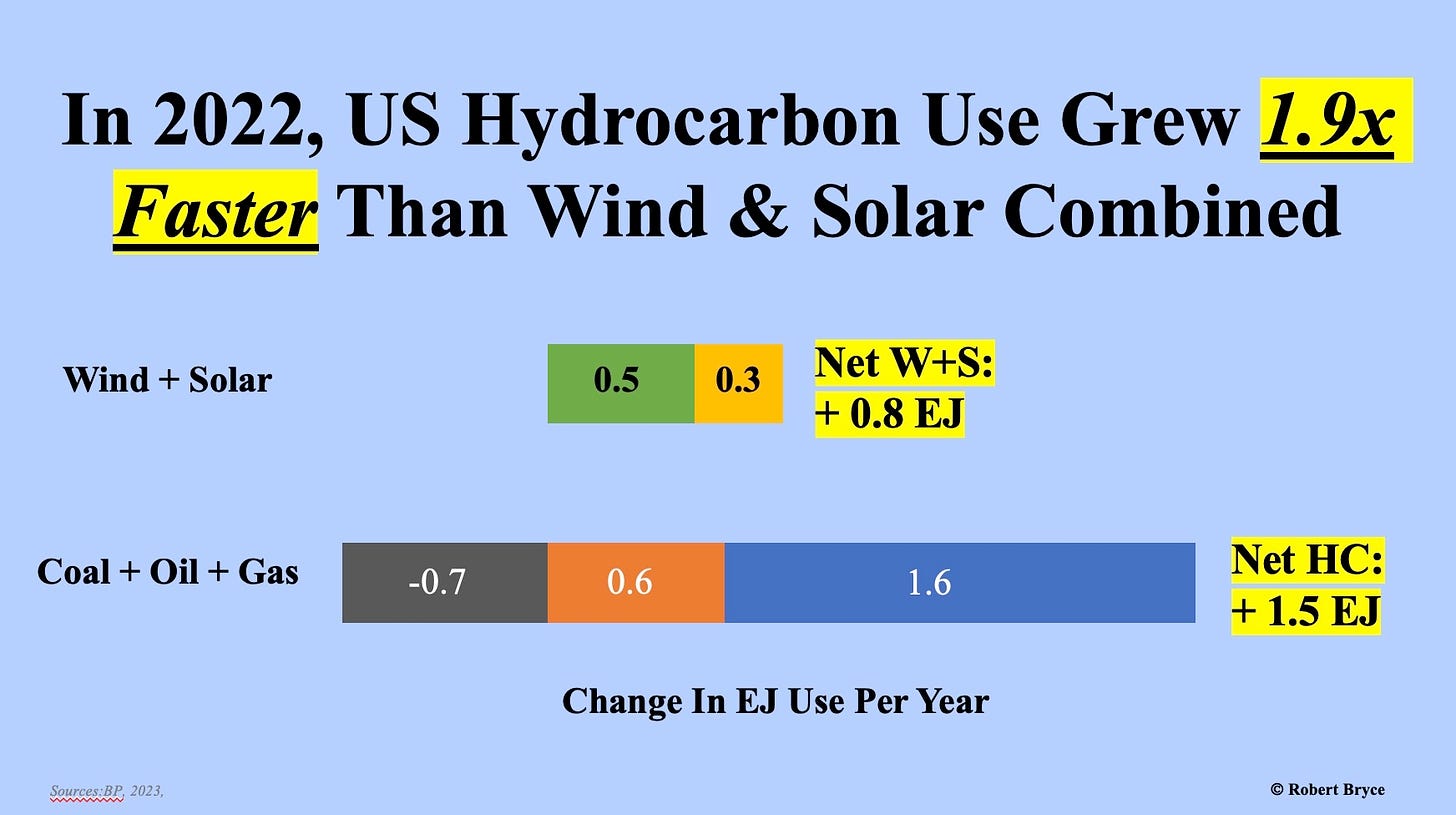

According to BNEF, between 2004 and 2022, U.S. spending on wind and solar totaled some $591 billion. Despite that massive investment, as can be seen in the graphic above, just the growth — repeat, just the growth — in natural gas consumption in 2022 was twice the growth in wind and solar combined. Coal demand fell by 0.7 EJ. Oil use grew by 0.6 EJ and gas grew by 1.6 EJ. Thus, the net growth in hydrocarbon use in the U.S. in 2022 was 1.5 EJ, or 1.9 times the growth seen in wind and solar combined. (An exajoule, an SI unit, is 1018, or 1 quintillion joules. An exajoule is roughly equal to one quadrillion Btu. It’s also roughly equal to the energy contained in 1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.)

Domestic gas use in 2022 jumped by a whopping 5.4% and hit a record 85.3 billion cubic feet per day. In March, the Energy Information Administration reported that gas consumption set monthly records in 9 of 12 months in 2022. Not only did annual use hit a new record, but the U.S. also set a new record for daily high demand. On December 23, U.S. gas use hit 141 billion cubic feet. The previous record was 137 billion cubic feet per day.

Lest you think 2022 was an anomaly, look at the graphic above, which shows a similar story in 2021, only the growth in hydrocarbons was even more substantial, with hydrocarbons outgrowing wind and solar by 5.7 times. The latest projections from the EIA expect the global consumption trends to continue. In March, the agency said it expects global liquid fuel use to go from 99.4 million barrels per day in 2022 to 100.9 MMbbl/d this year. But that figure has already been surpassed. This week, Enverus reported that global oil demand hit 101.5 MMbbl/d during the second quarter.

As I wrote 13 years ago in my fourth book, Power Hungry, “If oil didn’t exist, we’d have to invent it.” When tallying up its many attributes — energy density, ease of handling, scale, convenience, cost — it’s clear that oil is almost a miracle substance. Put simply, hydrocarbon use continues growing because coal, oil, and natural gas can provide the vast amounts of reliable, dispatchable energy that the world demands at prices consumers can afford. And like it or not, that will continue to be the case for years to come.

One final point: imagine how much further along the world would be today if the $4.1 trillion spent on wind and solar over the past 18 years had, instead, been spent on developing and deploying the next generation of nuclear power plants. That would be an energy transition worth writing about.