Inside the Underground Railroad Out of Afghanistan.

On Saturday night I had just sat down to have a drink with a friend when he got a call. He apologized for having to take it, but it was urgent: it was about the Afghan women’s orchestra. They were stuck in Kabul and desperate to get out. He was involved in the effort to extract them.

Twenty minutes later, we ordered another martini.

I’ve been thinking a lot these past two weeks about luck. The luck of where we are born. The luck of the parents we are born to. And, right now, the luck of who we know.

Knowing — or having proximity to someone who knows my well-placed friend, a veteran of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — is a matter of life or death for untold numbers of Afghans.

Listen to the plea of just one of them:

The question of who will live and who will die — part of the Unetaneh Tokef prayer that all Jews say on the high holy days, which are just around the corner — is supposed to be in the hands of God. But right now, for so many Afghans, the answer to that question is in the hands of the Taliban. The chance to live relies on Americans: those who have the luck to live in freedom and those who are determined to right what the Biden administration has gotten so horribly wrong.

Melissa Chen is one of those people.

Melissa co-founded an organization called Ideas Beyond Borders, which digitizes and translates English books and articles into Arabic. And not just any books: Books like Orwell’s ‘“Nineteen Eighty-Four,” Steven Pinker’s “Enlightenment Now,” and a graphic novel based on John Stuart Mill’s “On Liberty.” Works that promote reason, pluralism and liberty. Suffice it to say the translators she works with in places like Egypt, Syria and Iraq do so at great risk.

Because of her connections in the Middle East — and because she is the kind of person who lives by her principles — it did not surprise me that she found herself involved in the efforts to save Afghans from the horrors of the Taliban. She shares some of the details of those remarkable efforts in the essay below.

The operation to get American allies out of Kabul has been dubbed the Underground Railroad and Digital Dunkirk. But I can’t help but think of the MS St. Louis. That’s the ship that came to this country in 1939 packed with more 900 Jews fleeing Germany. To our country’s eternal shame we turned the ship around and into the arms of the Third Reich. — BW

For the past two weeks I have been part of a 21st century Underground Railroad. We are a ragtag group — combat veterans, human rights activists, ex-special forces, State Department officials, intelligence agents, members of Congress, non-profit organizers, and private individuals with the resources to charter planes and helicopters — who have stepped into the vacuum left by the Biden administration.

Today the Pentagon announced the end of our 20-year war in Afghanistan. But there are hundreds of Americans and an estimated 250,000 Afghan allies who remain trapped there. Many of these Afghans, due to the nature of their work, their religious beliefs, their minority ethnic status or even just their appearance (say, sporting tattoos anywhere on their bodies), see escape as a matter of life and death. As Kabul descended into chaos, their pleas for help leaving were largely met with bureaucratic silence.

The operation to save them began before the Taliban were seen riding bumper cars in amusement parks and occupying the presidential palace. Many veterans and civilians who had deep ties to the country were under no illusions about the nature of the Taliban and what a deal with them would mean for the people who had worked with the U.S.

Long before Kabul fell, I noticed that military friends started using Facebook and Twitter to figure out how to help their “terps” — interpreters, linguists and translators who served alongside them during their tours in Afghanistan. WhatsApp groups, email threads, and ad hoc task forces with their own central command centers sprang up spontaneously. Google docs were cobbled together to compile and share resources for individuals assisting their Afghan friends in their evacuation and eventual resettlement. No one was relying on a White House that had voluntarily closed Bagram Airbase or a commander-in-chief who, as of last month, was assuring the American public that a Taliban takeover “is not inevitable.”

No One Left Behind, a charity that was founded to help interpreters through the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program and resettle them in the U.S., has been at the vanguard of these efforts. Human Rights Foundation and Human Rights First were very effective in helping activists and dissidents secure political asylum. AfghanEvac, a self-organized group of beltway insiders and outsiders, have been logistical ninjas, chartering planes and requesting landing rights in neighboring countries. The Commercial Task Force set up shop in a conference room at the Willard InterContinental Hotel in Washington, D.C., and has so far helped evacuate 5,000 Afghan refugees. Republican Sen. Tom Cotton set up a war room office to take over the duties and responsibilities that the State Department had abdicated. Democratic Rep. Andy Kim had his office set up an email account to assist those seeking help evacuating allies.

And then there were the extraction teams like Task Force Pineapple and Task Force Dunkirk, informal, volunteer groups of U.S. veterans who took matters in their own hands to launch dangerous secret missions to save hundreds of at-risk Afghan allies and their families.

Because of my work with Ideas Beyond Borders, I wound up in one of these coalitions and joined several group chats on Telegram and WhatsApp. They would ping at all hours of the night with updates about the latest conditions on the ground and about assistance with particular cases. Any successful evacuation was announced and had its steps reverse-engineered in the hopes that it might help another hopeful evacuee.

It was in one of these groups that I met Esther Joy King.

King, a 35-year-old lawyer from Illinois who recently announced a run for Congress, had spent time in Kabul as an aid worker in 2008. But the seeds of her connection to Afghanistan were planted long before: Esther’s grandparents had immigrated there under the last King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah. Her grandfather taught at the American University of Kabul; her grandmother was a midwife; both were Christian missionaries. Esther’s mother, Susan King, was born in Kabul and spent the first nine years of her life there.

When Esther moved to Kabul for her aid work, Susan, together with her husband Robert, took the opportunity to visit. The Kings decided to stay on to start a K-12, co-ed school called Bahar International School in the Kart-e-Char neighborhood of Kabul. Susan taught English there until her cancer diagnosis just this year in February; she passed away in April. When she died, Esther filled in and took over her mom’s classes, teaching remotely until the end of the school term in May.

Three girls — Rahima, Mursal and Spoogemi — stood out in her class. They were eager to learn more, so Esther continued tutoring them well into the summer and ultimately secured three student visas for them in the U.S. The plan was for the girls to attend boarding school in Nebraska.

The story of one of those girls, 15-year-old Rahima, paints as accurate a picture as any about the chaos involved in, and the fortune required to get people out of Kabul.

Rahima made her first attempt at Karzai International Airport on August 16 with her student visa in hand. Amid the chaos, she Skyped Esther from 7,000 miles away. “Miss Esther,” she said, “I saw someone fall from the sky to die.” Flights shut down that day, so Rahima went to a safehouse to wait for further instruction.

Five days later, she made her second attempt. Rahima and her 13-year-old brother made it within 200 feet of the airport’s Abbey Gate. By this point, the State Department had outsourced visa and identity verification to the Taliban, quite literally putting the fox in charge of the henhouse. It was nightfall and the gates were already closed, so the siblings had no choice but to spend the night there, in front of the Taliban guards, who harassed them and beat them.

It was at this point that Esther told me she found out about a WhatsApp group with roughly 15 members including a former CIA agent and a former Marine who had connections on the ground. They had successfully extracted other girls from the school and felt they could do the same for Rahima.

Three days later, on August 24, the teenager and her family made their third attempt, armed with a map of Taliban checkpoints sent by someone from the WhatsApp group. They made it to the Abbey Gate without any obstacles. But the Marines wouldn’t acknowledge Rahima. The crowd was increasingly out of control, pushing them further and further back till she could no longer see the gate. The entire time, Rahima was sharing updates with the WhatsApp group.

There she learned that a particular U.S. Marine would be willing to extract her and her brother from the crowd. The catch was that they would have to wait till 2 AM, after his shift guarding a separate entrance ended. The plan was to gather at a certain tower where they, and another family with a baby in a pink hat, would be personally escorted into the airport. Passwords were coordinated: Pedro and Jolly.

At go time, Rahima turned on her flashlight to signal to the tower, trying to draw the Marines’ attention to her. No response. After 45 minutes, the WhatsApp group informed her that she was at the wrong tower. By now, Rahima was exhausted and defeated. She begged Esther to ask the Marine to come to them and not the other way around.

Knowing that was an impossibility, one of the women in the WhatsApp group, Erica Jensen of Omaha, Nebraska, had an idea. Her neighbor was an Afghan woman, so she ran across the street and banged on her door. What they needed was a very clear explanation of where Rahima needed to go with exact directions to the right tower in her native language, Dari. Stepping over sleeping bodies in the crowd, Rahima and her family made the trek and eventually found the Marine waiting for them.

Once through to the airport, the family still had to undergo biometric screening, waiting in lines for another 20 hours. Their ordeal did not end there. After they boarded a plane bound for Qatar, the pilot informed them that the destination — a military base in Doha — was so overcrowded that they had no authorization to take-off. Another 24 hours elapsed as the family sat in a Boeing C-17. Esther reached out to Rahima on WhatsApp, telling her that she couldn’t wait for her to to arrive in America.

Esther woke up early on Thursday morning to good news. Rahima and her family had made it to Kuwait. Asked how she even had cell phone reception, Rahima explained: “Oh, I borrowed a soldier’s hotspot.” The entire WhatsApp group received a message from the teenager that read: “I learned a precious lesson from you all, that I should always stand with people and help whenever I can.”

When I asked Esther how she did it, she replied, “miracles and persistence. Oh and WhatsApp. Thank God for WhatsApp.”

As for me, as Esther had been working on getting Rahima out, I had been fretting over a list. On August 17, I was part of a group that was given access to a list of 500 names of Afghan aid workers, human rights activists, and religious and ethnic minorities. When it became clear that the American government wasn’t doing enough, such lists started circulating among various volunteers. My heart sank when the person in charge of flight manifests asked us to split the list into “high priority” and just “priority.”

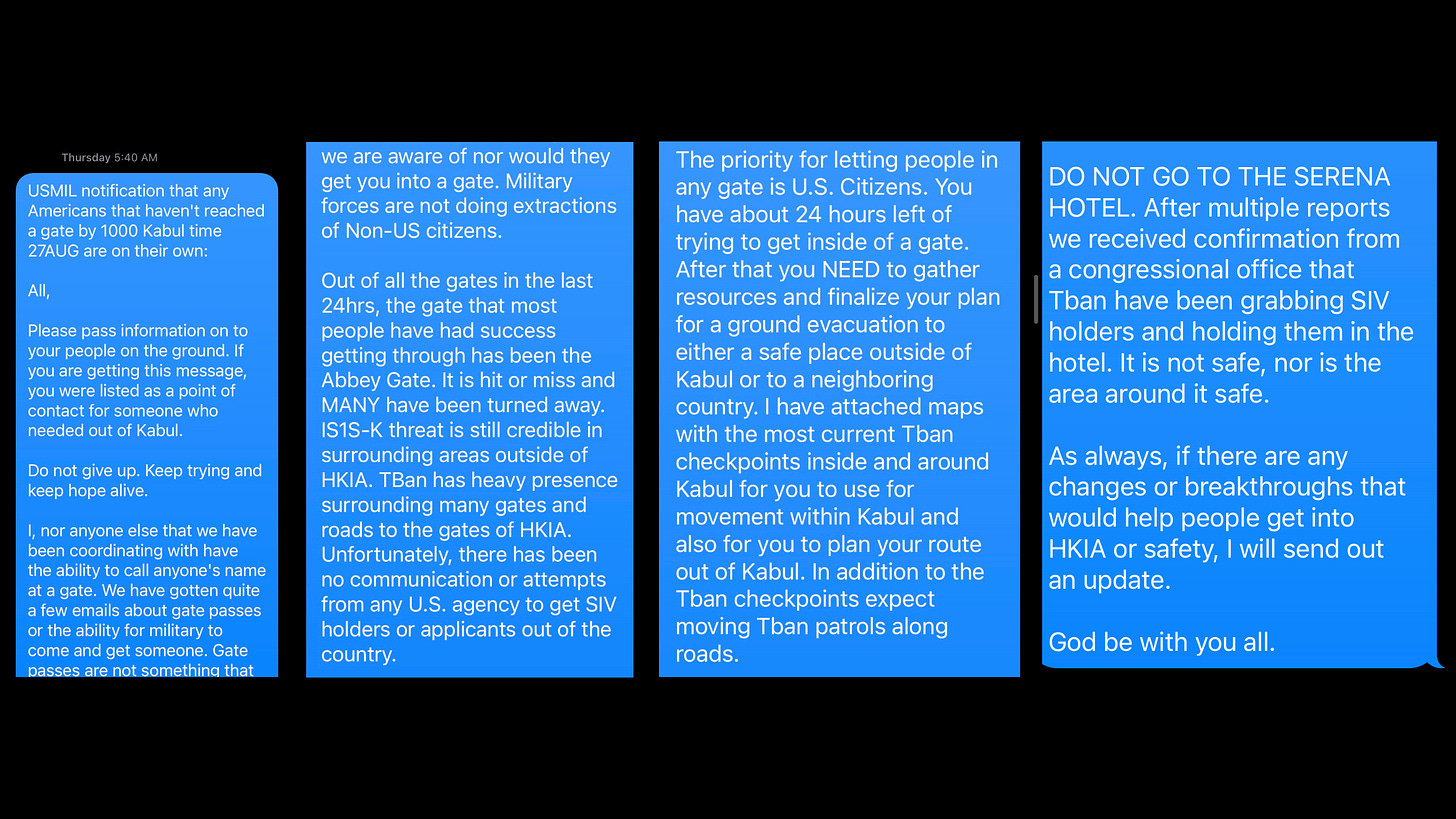

By Wednesday night, August 25, shortly after receiving a memo from the U.S. military that signed off with a bleak “may God be with you all,” I was asked to cut my evacuation list down to just five people.

I struggled with this intensely, especially after reading hundreds of emails with personal pleas, and poring over documentation of entire Afghan families with real faces and identities. I could not do it. But I had to do it. Along with my co-worker, Faisal Al Mutar, I ultimately did pick just five based on a basic evaluation of relative risk and ease of extraction. The moral weight of such a decision was overwhelming. We should have never been in a position to make such a call in the first place.

A few hours later, we got the devastating news that a suicide bomb went off right outside the Abbey Gate, taking the lives of 13 American service members and more than 90 Afghans. It was the same gate where Rahima and so many of Esther’s students and teachers had attempted to gain access to a departing plane.

Tomorrow is August 31, the Biden administration’s “hard deadline” for withdrawal. It’s clear that we won’t be able to evacuate all the Afghans we promised to protect. It’s clear that we won’t be able to help those Afghans, especially women and girls, who will now face the barbarism of Taliban rule.

But people like Esther are not giving up. She and her father are determined to continue helping bring more at-risk Afghans to safety. So far, they helped more than 50 people escape.

Meanwhile, my WhatsApp groups keep buzzing. My email inbox swells with requests. A young singer and model begs me to save her life: “Being an Afghan woman under the Taliban is tough enough but being a Muslim who sings songs and models is even more difficult. My life is in danger. Please help.”